![The staked Goat]()

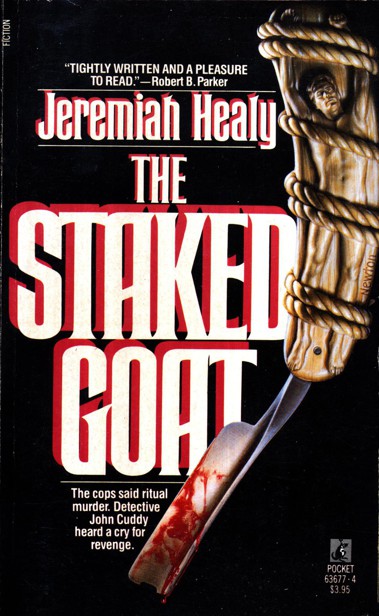

The staked Goat

Maybe one-eighty in shape, two hundred with his pot. I was tired, and he had that vaguely familiar look of many middle-aged noncoms. Bald, forty-five or so, with a Southwest twang in his voice.

”Just some cold water, if you can.”

I extended the pitcher as he said, ”Sure thing, sir.” I looked up at the clock. It said 16:45. He noticed me and shook the pitcher at me.

”Now, don’t you worry none about that clock, sir. Casey, Sergeant Casey, he told me you was here on something important, and I already called the missus. I’ll be here jest as long as you need. I got me a book and everything.”

There was a Louis L’Amour novel spread open face down on his desk.

”Thanks, Sergeant. I really appreciate it.”

”Would you like some coffee, sir? It’s no trouble.”

”No, thanks.”

”Jest be a minute.”

He was gone perhaps thirty seconds.

”Here you are, sir.”

”Thanks, Sergeant.”

”You jest take your time.” He smiled. ”There ain’t nothing goin’ on over in the old D. of C. on a cold Monday night in March anyways.”

I went back in, closed the door and sat back down. Mid-January 1968 became January 20, then January 25, then finally January 30. The dawn of the Year of the Monkey, the lunar New Year holiday all of Vietnam celebrated.

They called it ”Tet.”

Some military historians trace the strategic beginning of the Tet Offensive back to September 1967, in terms of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong planning and stockpiling in and around the cities of South Vietnam. Tet was really the first time the cities were hit, the VC up till then being a nearly invisible enemy, indistinguishable citizens by day, raiders in rural villages and an occasional town by dark. One North Vietnamese general suggested much later that since the offensive did not result in widespread, spontaneous uprisings by the people of South Vietnam, it was, in effect, a military defeat for Charlie. Americans who were there that night might disagree with him.

The Viet Cong caught the whole country sleeping. They attacked air bases, corps headquarters, National Police substations, even our Embassy, which squatted like a concrete sewage plant in a neighborhood of French villas on Thong Nhut. Al and I were sacked out in our BOQ when the first explosions awakened us. We got dressed and raced downstairs, the pop and crack of small-arms fire filling the air between the louder blasts of rockets and sappers’ satchel charges. We leaped with eight or ten others into a deuce-and-a-half-ton truck that barreled the mile or so to our headquarters.

The doorway to our station looked like the entrance to an anthill. MPs were scurrying in and out, passing, tossing, dropping equipment. Jeeps and deuce-and-a-halfs were pulling up and pulling out with a lot of noise but little pattern. The harried captain on duty split us up, Al drawing a barricade reinforcement north of the headquarters and me a recon by jeep toward the red-light district on Tu Do Street. Al was wounded almost as soon as he left the station, so I figured I would just skim the reports from the start of the attack onward. There was no reason for me to relive my memories. Still, the nightmare images from that night flashed back no matter how quickly I flipped the pages.

Two MPs, a young blond PFC and an older black sergeant, lying dead next to an overturned, burning jeep at a street corner. Both still held their .45s, jacked open and empty. Nine Viet Cong, some with automatic weapons, sprawled in a staggered attack formation in front of them. An incredible stand.

Four National Police officers stopping a vegetable truck. They pulled the driver out and shot him to death, rumor being that the VC had infiltrated their weapons and explosives for Tet in such vehicles.

A farmer, elderly with arthritic, stained fingers and a few long strands of chin beard. He wore a broad, peaked coolie hat and clutched a copy of Chinh Luan, the Vietnamese-language newspaper. He was sitting motionless in a corner of a blown-out building, staring at another corner. God knows how he came to be there or what happened to him afterwards.

A red-haired trooper, who had spent the entire night of the attack with a B-girl, being dragged between two MPs into the station. He looked so young, a ninth-grader being taken to the principal’s office for detention.

Viet Cong prisoners, the men in cheap white dress shirts, the women wearing white kerchiefs. All kneeling in gaggles of five or six, arms

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher