![The staked Goat]()

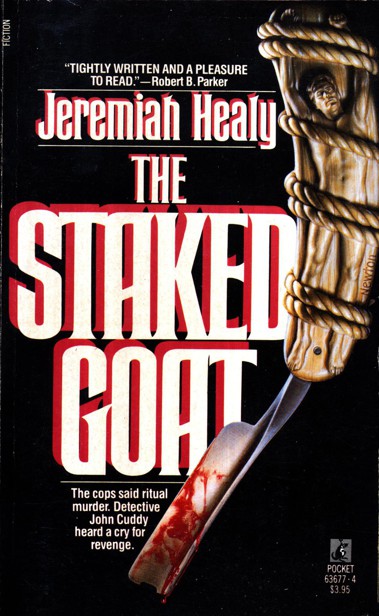

The staked Goat

goat to cry itself hoarse, straining against the leash. It took another hour for me to lose a pint of blood to the mosquitoes. Nothing moved in the bush.

I started to say something humorous. Master hissed and Van said, ”All quiet now.”

Another half an hour of nothing. I closed my eyes and thought of back home: summer Sundays on Carson’s Beach in Southie or Crane Beach in Ipswich, the Yankees against the Red Sox at Fenway Park, the (back-then-realistic) rivalry between Boston College and Holy Cross in football.

A stand of high grass rustled off to our right. Four heads whipped over there, five counting the goat’s. The bait had no more voice, but resumed hopping and tugging against the lead for all it was worth.

”Cop,” whispered Master. No need for translation now. Tiger.

More rustling, then a pause, then more rustling, then a pause. The unseen creature moved around the perimeter of the pond. Al tensed and eyed his weapon. I was to have the second shot, but I had no intention of firing unless the cat was coming straight at...

A stumble and crunch in the bush as the creature neared the virtually hysterical goat. Al seated the rifle butt against his shoulder. The creature cried out, not a roar, not a growl, just a simple word.

A seven- or eight-year-old girl, yelping what was probably the goat’s name, rushed up to it and began hugging it.

Master cursed. Van said, ”That is the girl from father that Master buy goat.” I remembered the child’s voice crying back at the village. The girl started trying to untie the goat’s lead.

Al said, ”Jesus,” and lowered his rifle. Master, still muttering curses, drew a knife and put it between his teeth. He started down the trunk.

”Van,” I said. ”Tell Master that if he touches the girl I will kill him.”

Master, who had probably heard the English word ”kill” often enough, nodded vigorously as if to confirm that was the goat’s, and possibly the girl’s, immediate destiny.

Al said, ”John...”

”Tell him,” I snapped at Van.

Master had started around the pond. Van spoke to him in Vietnamese. Master stopped, turned, and protested. Van said to me, ”American pay for tiger hunt, American get tiger hunt.”

I said, ”Tell Master he can keep the money. The girl keeps her goat, and the Americans go back. Now.”

Van translated. Master shrugged, sheathed his knife.

I said, ”Now tell the girl. Call to her. Tell her the Americans give her back her goat.”

Al said, ”John, for chrissakes, there may be VC within earshot.”

”Tell her,” I repeated.

Van called over to the girl. She succeeded in untying the goat, then bowed down to us as she led it off around the way she came.

She got maybe five meters when a mine exploded. The top half of her somersaulted through the air toward us. Head, arms, trunk to her waist. It splashed into the pond, scattering a roomful of insects. A few branches and clumps of grass and goat followed her trajectory into the water.

Al bit his lower lip, then lowered and shook his head. Van showed a tear. Master, who had hit the deck at the explosion, was standing up, brushing himself off.

”Let’s go,” I said, and climbed down out of the treehouse.

As we walked back to our perimeter, I wondered what kind of funeral the little girl would have. Not a military one. No flag-covered coffin, surely, the Stars and Stripes whipped down and tucked securely around the base.

The first time I remember seeing an American flag around a coffin was President Kennedy’s funeral. On television. A cold, blustery November Saturday. The riderless black horse, John-John saluting, the older males in the family walking solemnly uphill in mourning coats, their path lined by Green Berets with weapons at ”present arms,” bagpipes skirling.

My strongest memories, however, are of other military funerals. Or wakes, if you will; I guess the funerals took place back home. The wakes were in Vietnam, though. Three filthy, stinking GIs, standing over a sealed green body bag at some impromptu Graves Registration Point, alternately dragging on a joint and saying, ”Shit, man.”

It is, I think, the greatest irony of our time, at least of my time. A President I thought I understood and would have died for dropped us into a war in a country which none of us understood and where nobody should have died.

Seventeen

I REACHED THE POINT WHERE A L SHIPPED HOME. W E had a short-timer’s party for him at the Officers’

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher