![The Stone Monkey]()

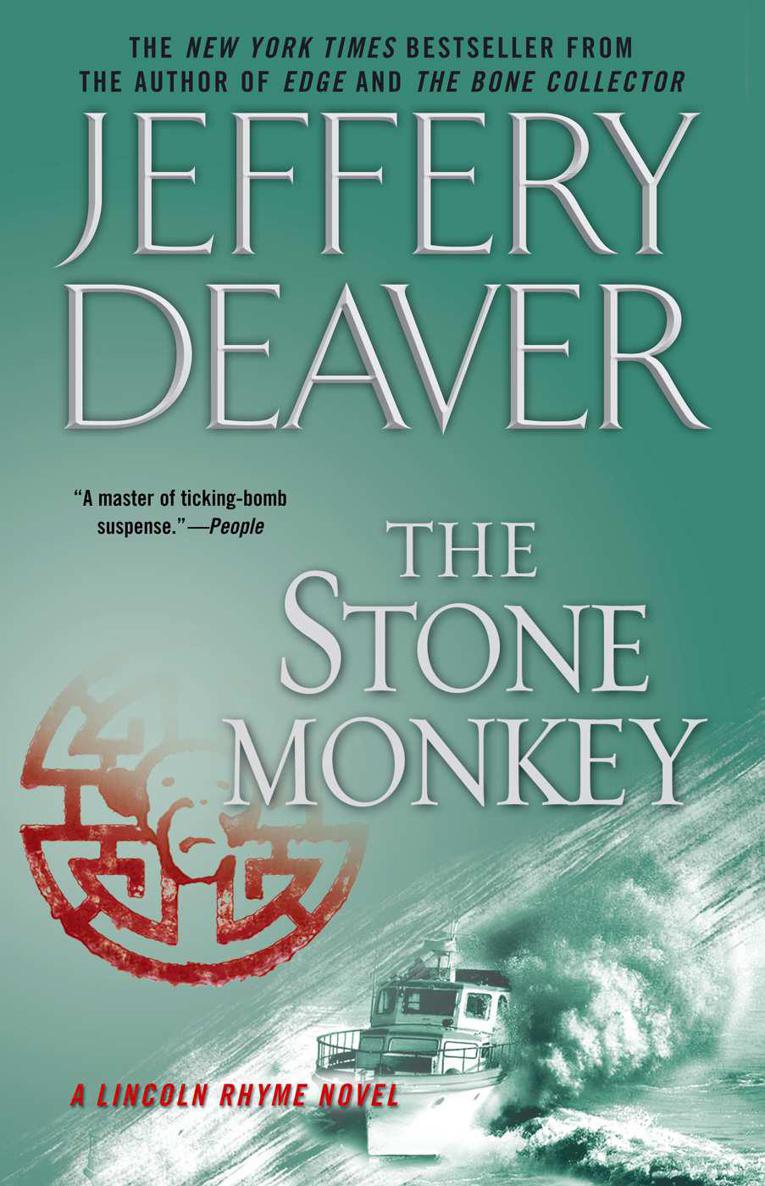

The Stone Monkey

straight.

—Your father

Sam Chang was seized with bottomless anger. He rose fast from the couch and, groggy from the drug, struggled to stay upright. He flung the teacup against the wall and it shattered. Ronald shied away from his enraged father.

“I am going to kill him!” he screamed. “The Ghost is going to die!”

His tirade started the baby crying. Mei-Mei whispered something to her sons. William hesitated but then nodded toward Ronald, who hefted Po-Yee. Together they walked into the bedroom. The door closed.

Chang said to her, “I found him once and I’m going to find him again. This time—”

“No,” Mei-Mei said firmly.

He turned to face his wife. “What?”

She swallowed and looked down. “You will not.”

“Don’t speak to me like that. You’re my wife.”

“Yes,” she said to him, her voice quavering, “I am your wife. And I’m the mother of your children. And what will happen to us if you die? Have you thought about that? We’d live on the street, we’d be deported. Do you know what life in China would be like for us when we returned? A widow of a dissident with no property, no money? Is that what you want for us?”

“My father is dead!” Chang raged. “The man responsible for that has to die.”

“No, he doesn’t,” she replied breathlessly, working up her courage once again. “Your father was an old man. He was sick. He was not the center of our universe and we must move on.”

“How can you say that?” Chang raged, shocked at her impudence. “He’s the reason I exist.”

“He lived a full life and now he’s gone. You live in the past, Jingerzi. Our parents deserve our respect, yes, but nothing more than that.”

He realized that she’d used his Chinese given name. He didn’t think she’d done so in years—not since they’d been married. When she addressed him, she always used the respectful zhangfu, “husband.”

In a steadier voice now Mei-Mei said, “You won’t avenge his death. You’ll stay here with us, in hiding, until the Ghost is captured or killed. Then you and William will go to work at Joseph Tan’s printing company. And I’ll stay here and teach Ronald and Po-Yee. We’ll all study English, we’ll make money . . . . And, when there’s another amnesty, we’ll become citizens.” She paused for a moment and wiped her face, from which tears streamed. “I loved him too, you know. It’s my loss as well as yours.” She resumed cleaning up.

Chang fell onto the couch and sat for a long time in silence, staring at the shabby red and black carpet on the floor. Then he walked to the bedroom. William, holding Po-Yee, stared out the window. Chang began to speak to him but changed his mind and silently motioned his younger son out. The boy warily stepped into the living room and followed his father to the couch. They both sat. After a moment Chang composed himself. He askedRonald, “Son, do you know the warriors of Qin Shi Huang?”

“Yes, Baba.”

These were thousands of full-size terra-cotta statues of soldiers, charioteers and horses built near Xi’an by China’s first emperor in the third century B.C . and placed in his tomb. The army was to accompany him to the afterlife.

“We’re going to do the same for Yeye.” He nearly choked on his sorrow. “We’re going to send some things to heaven so your grandfather will have them with him.”

“What?” Ronald asked.

“Things that were important to him when he was alive. We lost everything on the ship so we’ll draw pictures of them.”

“Will that work?” the boy asked, frowning.

“Yes. But I need you to help me.”

Ronald nodded.

“Take some paper there and that pencil.” He nodded toward the table. “Why don’t you draw a picture of his favorite brushes—the wolf-hair and the goat. And his ink stick and well. You remember what they looked like?”

Ronald took the pencil in his small hand. He bent over the paper, began his task.

“And a bottle of the rice wine he liked,” Mei-Mei suggested.

“And a pig?” the boy asked.

“Pig?” Chang asked.

“He liked pork rice, remember?”

Then Chang was aware of someone behind him. And he turned to see William looking down at his brother’s drawing. Somber-faced, the teenager said, “When Grandmother died, we burned money.”

It was a tradition at Chinese funerals to burn slips ofpaper printed to look like million-yuan notes, issued by the “Bank of Hell” so that the deceased would have money to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher