![The Tortilla Curtain]()

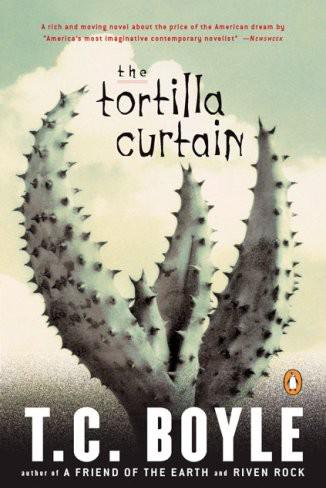

The Tortilla Curtain

the hunger drove her through the doors with her money and she bought another tin of sardines and a loaf of the sweet white bread that was puffed up like edible clouds and a Twix bar for Cándido. She was afraid someone would speak to her, ask a question, challenge her, but the girl at the checkout stand stared right through her and the price--$2.73--showed in red above the cash register; sparing her the complication of having to interpret the unfathomable numbers as they dropped from the girl's lips. Outside, back on her stump, she folded the sardines into slices of bread and before she knew it she'd eaten the whole tin. Her poor bleached fingers were stained yellow with the evidence.

And then the sun fell behind the ridge and the shadows deepened. Where was Cándido? She didn't know. But she couldn't stay here all night. She began to think about their camp again, the lean-to, the stewpot, the blanket stretched out in the sand, the way the night seemed to settle in by degrees down there, wrapping itself round her till she felt safe, hidden, protected from all the prying eyes and sharp edges of the world. That was where she wanted to be. She was tired, enervated, giddy from breathing fumes all day. She rose to her feet, took a final glance around and started off down the road with her bread, the Twix bar and her twenty-two dollars and twenty-seven cents all wrapped up in the brown plastic bag dangling from her wrist.

At this hour, the traffic had slowed considerably. The frenetic stream of cars had been reduced to the odd vehicle here and there, a rush of air, a hiss of tires, and then the silence of the canyon taking hold of the night, birds singing, the fragment of a moon glowing white in a cobalt sky. She looked carefully before crossing, thinking of Cándido, and kept to the edge of the shoulder, her head down, walking as fast as she could without drawing attention to herself. By the time she reached the entrance of the path she was breathing hard, anxious to get off the road and hide herself, but she continued past it, slowing her pace to a nonchalant stroll: a car was coming. She kept her head down, her footsteps dragging, and let it pass. As soon as it had disappeared round the bend by the lumberyard, she retraced her steps, but then another car swung round the curve coming toward her and she had to walk past the trailhead again. Finally there was a respite--no one coming either way--and she ducked into the bushes.

The first thing she did was relieve herself, just like last night. She lifted her dress, squatted over her heels and listened to the fierce impatient hiss of the urine as the light settled toward dusk and the smell of the earth rose to her nostrils. A moment ago she'd been out there on the road, exposed and vulnerable--frightened, always frightened--and now she was safe. But the thought of that frightened her too: what kind of life was it when you felt safe in the bushes, crouching to piss in the dirt like a dog? Was that what she'd left Tepoztlan for?

But that was no way to think. She was tired, that was all. Her shoulders ached and her fingers burned where the skin was peeling back from her nails. And she was hungry, always hungry. If she'd stayed in Tepoztlán through all the gray days of her life she would have had enough to eat, as long as her father was alive and she jumped like a slave every time he snapped his fingers, but she would never have had anything more, not even a husband, because all the men in the village, all the decent ones, went North nine months a year. Or ten months. Or permanently. To succeed, to make the leap, you had to suffer. And her suffering was nothing compared to the tribulations of the saints or the people living in the streets of Mexico City and Tijuana, crippled and abandoned by God and man alike. So what if she had to live in a hut in the woods? It wouldn't be for long. She had Cándido and she'd earned her first money and now Cándido was able to work again and the nightmare of the past weeks was over. They'd have a place by the time the rains came in the fall, he'd promised her, and then they'd look back on all this as an adventure, a funny story, something to tell their grandchildren. _Cándido__, she would say, _do you remember the time the car hit you, the time we camped out like Indians and cooked over the open fire, remember?__ Maybe they'd have a picnic here someday, with their son and maybe a daughter too.

She was holding that picture in her head,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher