![The Treason of the Ghosts]()

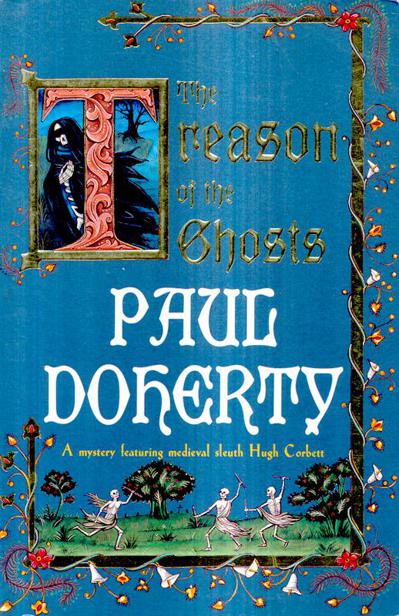

The Treason of the Ghosts

Peterkin’s

hands. The young man’s cheeks were bulging. Sorrel smiled. Sweetmeats! Her

smile faded. It jogged a memory. She had seen Peterkin feeding his face on many

occasions. Once, out in the countryside, she had come across the simpleton

carrying a small box of oranges, a rare fruit which cost a great deal. She’d

wondered then, and still did, how Peterkin could afford such a luxury. In fact,

he hadn’t been so stupid then but sharp-eyed and very defensive. He’d clutched

the box and scampered away. How could a witless wonder like him earn silver?

True, Melford was growing prosperous and Peterkin was used, especially by the

young gallants and swains, to carry messages to their loved ones.

Out

of the corner of her eye, Sorrel glimpsed a man sneaking up the steps of the

cross, his hand snaking out to grasp her sack. She quickly brought the cudgel

down and slapped his fingers. Repton the reeve, his sour face suffused in

anger, backed away.

‘Don’t

touch what’s not yours!’ Sorrel declared.

‘I

heard about your words with the bailiff,’ Repton sneered, nursing his

fingertips. ‘Stealing again, Sorrel?’

‘No,

I haven’t been stealing. I am an honest woman, Master Repton. I tell the truth,

on oath or not!’

The

sneer faded from Repton’s face. ‘What do you mean?’

He

glanced quickly to the left and right. The reeve now regretted his action. He

had drunk two quarts of ale at the Golden Fleece and knew Adela the serving

wench was watching him from a casement window. He had seen the ‘poacher’s

wench’; as he called Sorrel, climb the steps to the market cross and loudly

boasted he’d find out what she carried in her sack. Now his fingers burnt and

the ale had turned sour at the back of his throat.

‘You

know what I mean,’ Sorrel continued evenly. ‘The night Widow Walmer was

murdered. My man Furrell told me what he saw.’

Repton

made a rude sound with his lips. ‘I am not bandying words with you,’ he

sneered, and he swaggered away.

Sorrel

opened the sack, looked inside and grinned. Three fat pheasants: she’d trapped

each of them, slit their throats and hung them up for a day. The taverner

Matthew Alliot, mine host of the Golden Fleece, would pay good silver for

these.

‘Here

they come!’ a man cried.

Sorrel

clambered to her feet. Three horsemen had entered the marketplace just as the

church bell tolled for the midmorning Angelus. At first sight they didn’t look

like royal emissaries: no trumpeter, no herald, just men slouched in the

saddle, dark cloaks hitched about their shoulders, cowls pulled over their

heads, almost hiding their faces. Sorrel grasped the sack, and pushed and

shoved her way through the crowd and past the stalls. By the time she had

reached the entrance to the Golden Fleece, the three arrivals had dismounted,

and their horses were being led off by an ostler. Like men who had travelled

far, they were now loosening their cloaks, stretching to ease the cramp in the

small of their backs, thighs and legs. One of them was clearly a groom, smaller

than his two companions, dressed in a leather jacket like a soldier; a homely

face despite the cast in one eye. The tall, red-haired man with the lithe

figure of a street fighter must be Ranulf-atte-Newgate.

Sorrel

smiled as she shifted her gaze to Sir Hugh Corbett. Just as tall as his

red-haired companion, Corbett was darkfaced, his black hair, streaked with

grey, tied at the back. His clothes were of good quality: the jerkin, a white

shirt underneath, and hose of dyed blue wool; his high-heeled boots were the

best Spanish leather. Corbett carried his cloak over one arm and was busily

undoing his sword belt. He was looking up at the Golden Fleece as if memorising

every detail before turning to glance across the marketplace. Sorrel liked to

compare men to animals or birds. Yes, she thought, you are a greyhound, dark

and swift like an arrow, a hunter of souls. Or a falcon? Yes, a bird of prey which soared high, gliding and moving, its eyes always

watchful before the killing swoop. Sorrel felt a thrill of pleasure. This man

would pursue matters to the bitter end. He was no pompous royal official,

dressed in a gaily coloured tabard, proclaiming his every step to the tune of

tambour and trumpet. A stealthy man, Sorrel concluded, who would come like a

thief in the night and few would know the day or the hour.

Sorrel

watched as the arrivals swept into the Golden Fleece, then followed close

behind. She was

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher