![The Treason of the Ghosts]()

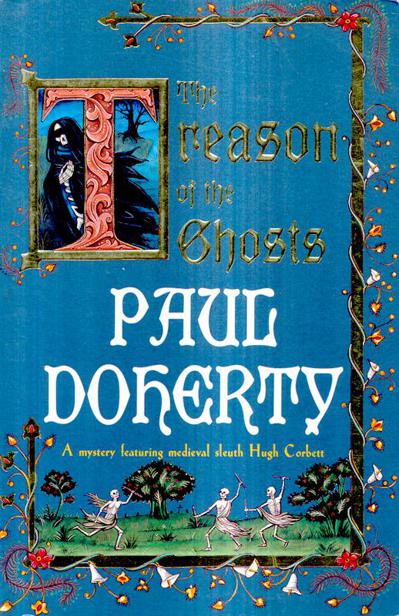

The Treason of the Ghosts

the trees far away she

thought she had seen a movement. Was someone there? Perhaps a

shepherd or his boy? Elizabeth felt a shiver; the weather was certainly turning. She wished she’d brought a

shawl or coverlet.

Elizabeth entered the trees. She loved this place. She used to come here as a child and

pretend to be a queen or a maiden captured by a dragon. She threaded her way

across the cold, wet grass and sat at the edge of the small glade, on the same

rock she used to imagine as her throne or the dragon’s castle. It was very

silent. For the first time since this adventure began, Elizabeth ’s conscience pricked at deceiving

her parents. Her happiness was laced with guilt and a little fear. This place

was so lonely — just the distant call of the birds and the faint rustling in

the bracken. Elizabeth shut her eyes and squeezed her lips.

I’ll

only wait here for a short while, she promised herself.

Time

passed. Elizabeth rubbed her arms and stamped her feet. She shouldn’t have come so publicly,

swinging her arms crossing that field. Perhaps her secret admirer had seen

someone else and been frightened off? In Melford, gossip and tittle-tattle, not

to mention mocking laughter, could do a great deal of harm. She should have

come along Falmer Lane and slipped through the hedge at Devil’s Oak.

Elizabeth heard

a sound behind her, the crack of a twig. She turned, her mouth opened in a

scream. A hideous, masked figure stood right behind her: the garrotte string

spun round her throat and Elizabeth the wheelwright’s daughter had not long to

live.

Chapter 2

Punishment

in the King’s royal borough of Melford always attracted the crowds, even more

so than a branding at the crossroads or a fair on the outskirts. The good

townspeople flocked to see justice done, as well as collect scraps of scandal

and gossip. Which traders had been selling underweight? Which bakers mixed a

little chalk with their flour or sold a load beneath the market measure? Above

all, they wanted to discover what house-breakers had been caught, pickpockets

arrested.

On

that particular October day, the crowds had an even greater reason for flocking

in. Word had soon spread, how the murders of Molkyn the miller, Thorkle, not to

mention that of poor Elizabeth Wheelwright, whose ravished corpse lay sheeted

for burial in the crypt of the parish church, had eventually reached the royal

council in London .

The King himself had intervened, not by dispatching justices or commissioners

of enquiry but officials from his own chamber, a royal clerk, the keeper of the

King’s Secret Seal, Sir Hugh Corbett and his henchman, Ranulf-atte-Newgate,

principal Clerk in the Chancery of the Green Wax. The people of Melford wanted

to view this. Oh, they desired an end to the horrid murders. They also wanted

to see a King’s man arrive, with all his power and authority, to enquire into

this or that, to execute the royal Writ, bring malefactors to justice and publish the Crown’s justice for all to see.

And,

of course, there was the mystery. Who had been responsible for the ghastly

murders of Molkyn and Thorkle? Killings took place, even in a town like

Melford, but to decapitate the likes of Molkyn and send his burly, fat head

across the mere of his mill! Or Thorkle, a prosperous yeoman farmer, having his

brains dashed like a shattered egg in his own threshing barn! Surely someone

would hang for all that?

And

those other heinous murders, the ravishing and slaying of young maidens? They

had begun again. One wench had been slaughtered late last summer, her torn body

being brought across this very marketplace. Now Elizabeth,

the wheelwright’s daughter, with her flowing hair and pretty face. She

had been well known, with her long-legged walk and merry laugh, to many of the

market people. Such gruesome murders should never have occurred! Hadn’t the

culprit been caught five years earlier and hanged on the soaring gibbet at the

crossroads overlooking the sheep meadows of Melford? And what a culprit! No less a person than Sir Roger Chapeleys, a royal knight, a manor

lord. The evidence against Chapeleys, not to mention the accounts of

witnesses had, despite royal favour, dispatched him to the common gallows.

Nevertheless, the murders had begun again and so the King had intervened. What

was his clerk called? Ah yes, Sir Hugh Corbett. His name was well known. Hadn’t

he been busy in the adjoining shire of Norfolk some years ago? Investigating murders along

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher