![The Treason of the Ghosts]()

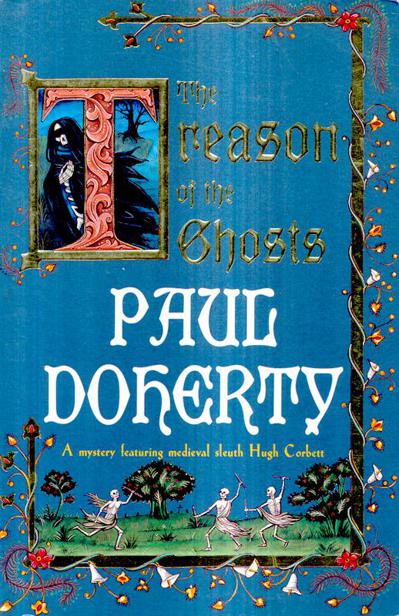

The Treason of the Ghosts

the lonely coastline of the Wash ? A formidable man,

the people whispered, of keen wit and sharp eye. If Corbett had his way, and he

had all the power to achieve it, someone would certainly hang.

The

day was cloudy and cold but the crowds thronged around the stalls. Those in the

know kept a sharp eye on the broad oak door of the Golden Fleece tavern, where

the royal clerk would stay. He would probably arrive in Melford with a

trumpeter, a herald carrying the royal banner and a large retinue. Urchins had

been paid to keep a lookout on the roads outside the town.

In

the meantime, there was trading and bartering to be done. Melford was a

prosperous place, and the increasing profits from the farming of wool were

making themselves felt at every hearth and home. Silver and gold were becoming

plentiful. The markets of Melford imported more and more goods from the great

cities of London , Bristol and even abroad! Vellum

and parchment, furs and silk, red leather from Cordova in Spain . Testers, blankets and

coverlets from the looms of Flanders and Hainault, not to mention statues, candlesticks and precious ornaments

from the gold- and silversmiths of London and, even occasionally, the great

craftsmen of Northern Italy.

Walter

Blidscote, chief bailiff of the town, loved such busy market days. He made a

great play of imprisoning the vagrants, the drunkards and law-breakers in the

various stocks on the stand at the centre of the marketplace. This particular

day he proclaimed the pickpocket Peddlicott. Blidscote himself had caught the

felon trying to rifle a farmer’s basket the previous morning. Blidscote was

fat, sweat-soaked but very pompous. He drank so much it was a miracle he caught

anyone. Peddlicott, however, was dragged across the marketplace as if he was

guilty of high treason rather than petty theft. He was displayed on the stand

and, with great ceremony, the market horn being blown to attract everyone’s attention, Peddlicott’s hands and neck were tightly secured

in the clamps. Blidscote loudly proclaimed that they would remain so for the

next twenty-four hours. If the bailiff had had his way, he would have added

insult to injury by tying a bag of stale dog turds around the poor man’s neck.

Some bystanders cheered him on. Peddlicott shook his head and whined for mercy.

Blidscote

was about to tie the bag tight when a woman’s voice, strong and clear, called

out, ‘You have no authority to do that!’

Blidscote

turned, the bag still clutched in his greasy fingers. He recognised that voice

and narrowed his close-set eyes.

‘Ah,

it’s you, Sorrel.’

He

glared at the strong, ruddy-faced, middle-aged woman who had shouldered her way

to the front of the crowd. She was dressed in stained brown and green, a sack

in one hand, a heavy cudgel in the other.

‘You

have no right to interfere in the town’s justice,’ Blidscote said severely.

‘Punishments are for me to mete out. And what do you have in that sack?’ he added

accusingly.

‘A

lot more than you have in your crotch!’ the woman retorted, drawing shouts of

laughter from the crowd.

Blidscote

dropped the bag and climbed down from the stand.

‘What

do you have in the sack, woman? Been poaching again, have you?’

Sorrel

threw back her cloak and lifted the cudgel warningly.

‘Don’t

touch me, Blidscote,’ she whispered hoarsely. ‘You have no authority over me. I

don’t live in this town and I’ve done no wrong. Touch me and I’ll cry assault!’

Blidscote

stepped back. He was wary of this woman, the common-law widow of Furrell the

poacher.

‘Been

busy, have you?’ he added spitefully. ‘Still wandering the woods and fields,

looking for your husband? He had more sense than to stay with a harridan like

you! He’s over the hills and miles away!’

‘Don’t

you talk of my man! ’ Sorrel snapped. ‘My man Furrell

is dead! One of these days I’ll find his corpse. If you were a good bailiff

you’d help me. But you are not, are you, Walter Blidscote? So keep your paws

off me!’

Blidscote

made a rude gesture with the middle finger of one hand. He went to pick up the

bag of turds.

‘And

leave poor Peddlicott alone,’ Sorrel warned. ‘The punishment said nothing about

such humiliation. Loosen the stocks a little.’

She

pointed at Peddlicott’s face, now a puce red. The bailiff was about to ignore

her.

‘It’s

true!’ someone shouted, now sorry for the pickpocket’s pain. ‘No mention was

made, master bailiff, of dog

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher