![Three Seconds]()

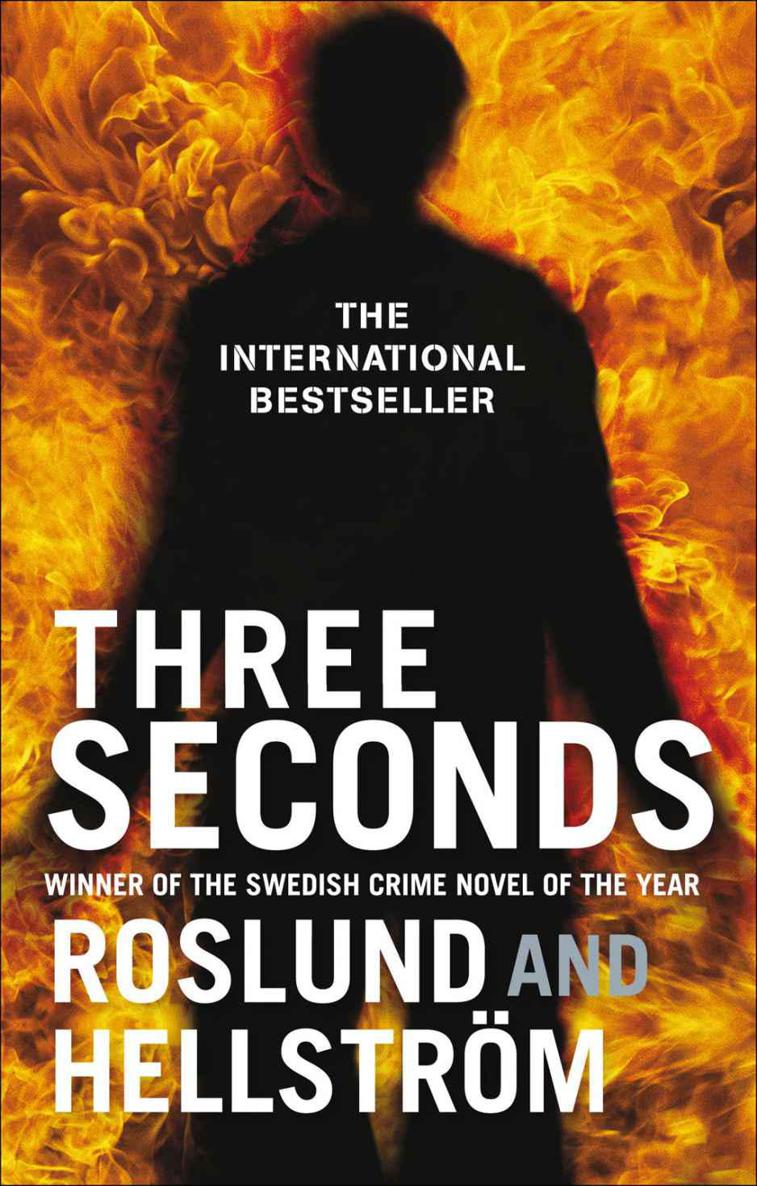

Three Seconds

exactly where the camera was and twigged it early, looked into it for a bit too long, looked into the lens aware that his presence had been documented.

Piet Hoffmann had knocked on the door just like all the others but had not been let in immediately like them. He was instructed to stay in the corridor, to hold out his arms while Göransson frisked him. Grens found it hard to stand still when he realised that the loud noise he had heard about nine minutes into the recording was the chief superintendent’s hand knocking the microphone.

He was speeding and slammed his foot on the brake when the turning to Aspsås emerged from the dark.

A couple more kilometres; he wasn’t laughing yet, but he was smiling.

Sunday was only a few hours old. He didn’t have much time but he would manage, still more than twenty-four hours left until Monday morning, when the security company’s report of the weekend’s surveillance tapes was passed on to the Government Offices’ security department.

He had heard the voices, and now he had seen pictures as well.

He would shortly confirm the connection between three of themeeting participants and the orders that a prison governor had been given before and during a hostage drama that ended in death.

__________

A terraced house on a terraced house road in a terraced house area.

Ewert Grens parked the car in front of a letter box with the number fifteen on it and then sat there and looked at the silence. He had never liked places like this. People who lived too close to each other and tried to look alike. In his big flat in Sveagatan, he had someone walking on his ceiling and someone else standing under his floor and others who drank glasses of water on the other side of the kitchen wall, but he didn’t see them, didn’t know them, he heard them sometimes but he didn’t know what they were wearing, what kind of car they had, didn’t have to meet them in their dressing gown with the newspaper under their arm and didn’t need to think about whether their plum tree was hanging a little too low over the fence.

He could hardly stand himself.

So how the hell was he going to stand the smell of barbecued meat and the sound of footballs on wooden doors?

He would ask Sven later, when this was all over, how you do it, how you talk to people you’re not interested in.

He opened the door and got out into an almost balmy spring night. A couple of hundred metres away stood the high wall, a sharp line against the sky that refused to go dark and would continue to do so until yet another summer had turned into early autumn.

Square slabs in a well-trimmed lawn, he walked up to the door and looked at the windows that were lit both downstairs and up: probably the kitchen, probably the bedroom. Lennart Oscarsson lived the other side of his life only a few minutes’ walk from his workplace. Grens was sure that being able to cope with living in a terraced house was somehow connected to not needing to separate one reality from the other.

His intention was to surprise. He hadn’t phoned to say he was coming, had hoped to meet someone who had just been asleep and therefore didn’t have the energy to protest.

It wasn’t like that.

‘You?’

He remembered Hermansson’s description of a person on the edge.

‘What do you want?’

Oscarsson was wearing the prison uniform.

‘So you’re still working?’

‘Sorry?’

‘Your clothes.’

Oscarsson sighed.

‘In that case I’m not alone. Unless you’ve come here in the middle of the night to have some tea and help me with the crossword?’

‘Will you let me in? Or do you want to stand out here and talk?’

Pine floors, pine stairs, plain walls. He guessed that the prison governor had done up the hall by himself. The kitchen felt older: cupboards and counters from the eighties, pastel colours that you couldn’t buy any more.

‘Do you live here on your own?’

‘These days.’

Ewert Grens knew only too well how a home sometimes refuses to be changed and a person who has moved out somehow seems to stay in the colours and furniture.

‘Thirsty?’

‘No.’

‘Then I’ll have a drink myself.’

Lennart Oscarsson opened the fridge, neat and well stocked, vegetables at the bottom, the beer bottle that he was now holding in his hand from the top shelf.

‘You nearly lost a good friend yesterday.’

The governor sat down and took a swig without answering.

‘I went to see him this morning. Danderyd hospital. He’s

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher