![Three Seconds]()

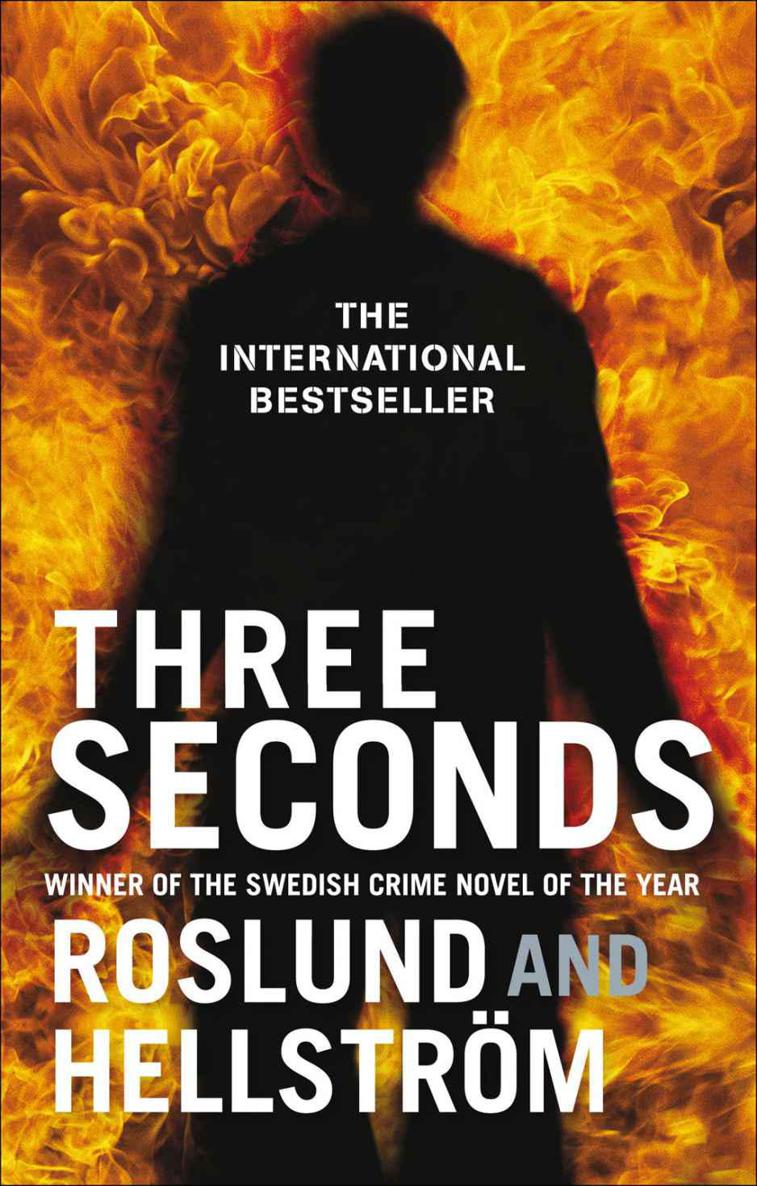

Three Seconds

substantial walls, which looked more like Lego blocks in their own world than ever before.

He looked towards the window he had chosen and aimed at it with an imagined gun, then took a silver receiver from his pocket – an earpiece identical to the one that was now hidden in a cavity in the left-hand margin of

The Marionettes

. He leant over the railing, for a moment feeling like he might fall to the ground, and he held on to the iron railing with one hand while he checked that the two transmitters, a black cable and a solar cell were still properly fixed where they should be. He put the receiver in his ear and one finger on a transmitter and ran it lightly back and forth – a crackling and snapping in his ear told him it was working fine.

He went down again, to the graves that lay side by side, but not too close, to the mist that blotted out death.

A merchant and his wife. A senior pilot and his wife. A mason and his wife. Men who had died as titles and professions and women who had died as the wives of their betitled husbands.

He stopped in front of a stone that was grey and relatively small and the resting place of a captain. Piet Hoffmann saw his father, the way he imagined him at least, the simple boat that had gone out from the border area between Kaliningrad and Poland and disappeared with its fishing nets over the Danzig Bay and Baltic Sea for weeks on end, his mother who later stood there and watched the slow progress into shoreand then ran down to the harbour and his father’s embrace. That wasn’t how it had been. His mother had often talked about the empty nights and the long wait, but never about running feet and open arms, that was the picture he had painted for himself when he, as a child, had asked curious questions about their lives in another time, and it was the image he chose to keep.

A grave that hadn’t been looked after for years. Moss crept over the corners of the stone and the small bed was overgrown with weeds. That was the one he was going to use. Captain Stein Vidar Olsson and wife. Born 3 March 1888. Died 18 May 1958. He had lived to be seventy. Now he was not even a gravestone that people came to visit. Piet Hoffmann held his mobile phone in his hand, his contact with Erik that would be cut in less than two hours. He turned it off, wrapped it in clingfilm, put it in a plastic bag, got down on his knees and started to dig up the earth with his hands at the bottom right of the headstone, until he had a sufficiently large hole. He looked around, no other dawn visitors in the churchyard, dropped the telephone into the ground and covered it with earth and then hurried back to the car.

__________

Aspsås church was still veiled in morning mist. The next time he would see it would be from the window of a cell in a square concrete building.

He’d managed it. He’d finished all his preparations. Soon he would be entirely on his own.

Trust only yourself.

He missed her already. He had told her and she hadn’t said a word, somehow like being unfaithful – he would never touch another woman, but that was how it felt.

A lie that was never-ending. He, if anyone, knew all about it. It just changed shape and content, adapted to the next reality and demanded a new lie so that the old one could die. In the past ten years he had lied so much to Zofia and Hugo and Rasmus and all the others that when this was all over, he would have forever moved the boundary between lies and truth; that was how it was, he could never be entirely sure where the lie ended and the truth began, he didn’t know any longer who he was.

He made a sudden decision. He slowed down for a few kilometres and let it sink in that this really was the last time. He had had a feelingall year and now it had caught up with him, now he could feel it again and interpret it. That was how he worked. At first something vague that tugged at him somewhere in his body, then a period of restlessness when he tried to understand what it meant, then insight, a sudden, powerful understanding that had been so close for so long. He would sit out this sentence at Aspsås and he would finish his work there, and after that, never again. He had done his service for the Swedish police, for little thanks other than Erik’s friendship and ten thousand kronor a month from their reward money, so that he didn’t officially exist. He was going to live another life later, when he knew what a true life really looked like.

__________

Half past

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher