![Up Till Now. The Autobiography]()

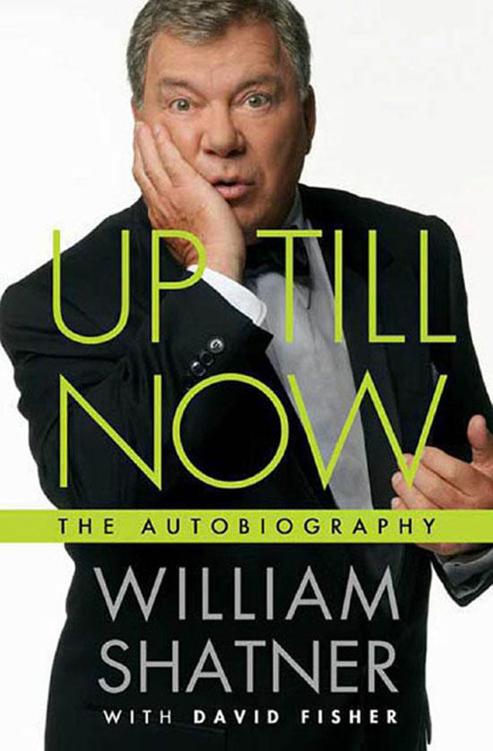

Up Till Now. The Autobiography

right, you name the price you want to pay. At Priceline.com it’s as simple as that. Here’s the way...

Opening this book like that would be funny, yet accurate, as many people know me from my work representing various companies, such as Priceline.com. And if we also could sell a few more copies of this book, well, I didn’t think St. Martin’s would object. And if Priceline was approached properly by my agent, perhaps they might even be willing to purchase the rights to the opening paragraph. For less than full price, of course.

But perhaps that was too crass for the opening of my autobiography, I decided. Is that really what I wanted to emphasize about my life and my career? And would Priceline meet my price? So that opening too, was rejected.

And then it occurred to me: I don’t need an opening. By the time you’ve reached this paragraph my autobiography has already started. Of course that was very similar to my career; I was already in the middle of it before I realized it had begun.

The first time I stood on a stage I made the audience cry.

Let me establish the rules for this book. I will tell all the jokes unless I specifically identify a straight line. In which case you will have the opportunity make up the jokes.

I was six years old, attending Rabin’s Camp, a summer camp for Jewish welfare cases run by my aunt in the mountains north of Montreal. I wanted to box at that camp—hitting people seemed like fun—but my aunt instead put me in a play named Winterset . My role was that of a young boy forced to leave his home because the Nazis were coming. In the climactic scene I had to say good-bye to my dog, knowing I probably would never see him again. My dog was played by another camper, costumed in painted newspaper. We performed the play on parents’ weekend to an audience consisting primarily of people who had escaped the Nazis, many of whom still had family members trapped in Hitler’s Europe. So many of them had left everything they knew or owned behind—and there I was, saying good-bye to my little doggie.

I cried, the audience cried, everybody cried. I remember taking my bow and seeing people wiping away their tears. I remember the warmth of my father holding me as people told him what a wonderful son he had. Just imagine the impact that had on a six-year-old child. I had the ability to move people to tears. And I could get approval.

Something in me always wanted to perform, always wanted the attention that came from pleasing an audience. Years before my camp debut my older sister remembers my mother taking the two of us downtown. Apparently I ran away and it took them several hectic minutes to find me—dancing happily in front of an organ-grinder.

Where did that come from? That need to please people? What part of me was born with the courage to stand in front of strangers and risk rejection? There was nothing at all like that in my family history. The Shatner family was Polish and Austrian and Hungarian, and apparently several of my forebears were rabbis and teachers.Like so many Jewish immigrants my father was in the schmatta business—he manufactured inexpensive men’s suits for French-Canadian clothing stores. Admiration Clothes. They were basically suits for workingmen who owned only one suit. Joseph Shatner was a stern but loving man, a hard-working man. I can close my eyes and remember the smell of his cutting room. The unforgettable aroma of raw serge and tweed in rolled-up bales, mixed with the smell of my father’s cigarettes. Saturday afternoon was the only time he would relax, lying on the couch and listening to New York’s Metropolitan Opera on the radio. He came to Montreal from Eastern Europe when he was fourteen, and worked selling newspapers and in other labor-intensive jobs. He started in the clothing business packing boxes and eventually became a salesman and finally started his own small company. He was the first member of his family to come to North America, but eventually he helped all ten of his brothers and sisters leave Europe. My friend Leonard Nimoy likes to joke about the fact that I never stop working; he does an imitation of me in which he says, “It’s quarter of four. What’s scheduled for four-ten? If I’m done there by four-thirty can we get something for four-fifty?”

Perhaps there is some truth to that. Every actor has spent days . . . months staring at the telephone, willing it to ring. And living with the hollow fear that it might never

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher