![Up Till Now. The Autobiography]()

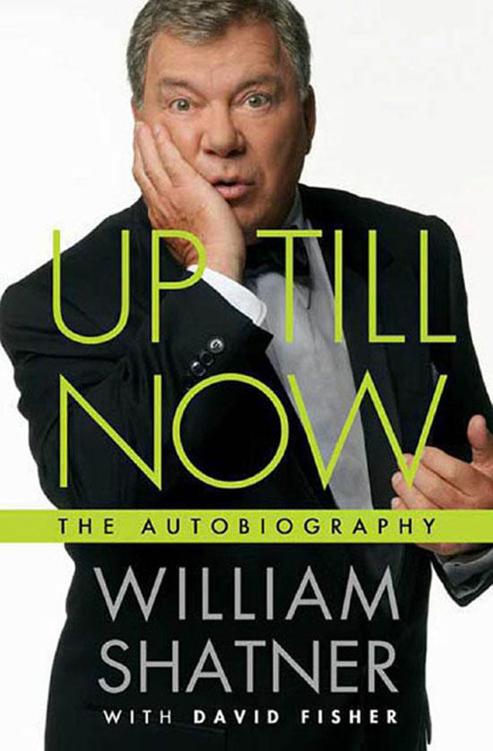

Up Till Now. The Autobiography

When an impressionist did Jimmy Stewart or Edward G. Robinson or Jimmy Cagney or Cary Grant, I knew exactly who they were doing. I always wondered, if Jimmy Cagney and James Stewart were having dinner at home, did Cagney say, “Pass the salt, you dirty rat?” And did James Stewart reply, “Um, ah, ah, ah, I...I...here... here it is.” But when I watch them doing me, speaking that. Way. The audience laughs. So it must be what. I’m doing. But I don’t recognize it in myself.

One thing that often does happen to an actor is that elements of the character they’re playing seep over into their real life. It’s quite different from speech patterns. You can’t go to work every day playing a monstrous man and then go home at night and enjoy a party. The intensity of the work is too strong. You have to inhabit the character’s body, and the transition back and forth between the character’s life and real life is often a difficult one to make. When we were making Star Trek , for example, Leonard Nimoy remained true to Spock the whole day. He couldn’t easily go in and out of a taci-turn, cerebral, emotionless character like that and as a result remained distant from the rest of us. Sometimes when a role is completed it’s very difficult to shed your character and move into a completely different life. In the early days of television it was easier because the whole job lasted less than a week. There wasn’t time to get deeply invested in a character. But now I had spent months trying to understand and portray the worst kind of racist, and then an assistant prosecutor of the people who had provided legal cover for unimaginable atrocities to take place. It was time for comedy.

The wonderful actress Julie Harris was going to star on Broadway in A Shot in the Dark , an English version of the French farce L’Idiot , and she decided she wanted me to co-star with her. I don’t know why, I’d never met her, but apparently she’d seen me on television and wanted me. I remember what my agent said when he called to tell me about this: “Trust me, Bill. This play is going to make you a star.”

More than anything else, I love being on the stage. At times duringmy career I’ve been able to connect emotionally with an entire audience, and during those rare moments it literally feels as if a relationship exists between us. We’re in this experience together. And this was an opportunity to do a farce and work with the legendary director Harold Clurman. Clurman had been a founding member of the Group Theatre, he was involved in the original Broadway production of Waiting for Lefty , and except for the fact that he did not want me in his play and did everything possible to make my life miserable— except kick me in the pants—we got along very . . . badly.

He seemed to get some sort of perverse joy out of insulting me: Just what do you think you’re doing? What are you, trying to be charming? No, no, no, that’s not the way to play it. And just how long have you been acting?

In addition to Julie Harris, the play co-starred Walter Matthau and Gene Saks. I played French Examining Magistrate Paul Sevigne, who is investigating his first case, a murder in which the beautiful parlor maid was found unconscious, naked, and holding a gun next to the body of the dead chauffeur. Naturally, as this was a farce, I didn’t believe she had committed the crime.

Matthau played the fabulously wealthy Benjamin Beaurevers, who may have been having an affair with the maid. The play got nice reviews and ran for eighteen months. But there was one moment during the entire run that I will never forget. Walter and I were playing a scene across a table; basically I was accusing him of committing the murder and he was accusing me of being an idiot. Something happened, truthfully I don’t remember what it was. I could make something up but . . .

In fact, I will make something up. It makes for a better story. And honestly, I do make things up. It’s part of the actor’s craft. For example, and I’m not making this up, I used to love to ride motorcycles with stuntmen I’d met while making Star Trek in the desert. We’d race through Antelope Valley, in Palmdale, and in those years there were a lot of stories about Unidentified Flying Objects, UFOs, being seen in that area. There was a photograph of one hovering directly above a power line. So when I rode in the desert I’d look into thesky. I figured if the aliens could read my thoughts

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher