![What became of us]()

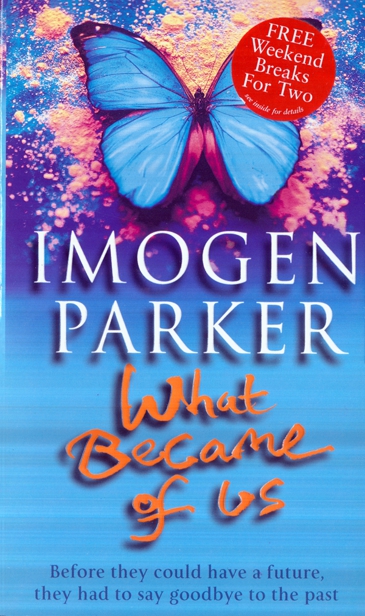

What became of us

from black to grey. She pulled out the plug with her toes, then stood up, surveying herself in the long mirror on the back of the bathroom door looking for signs, but there was no visible difference. She took another towel, stepped out and dried herself, then took another look at her long, slim body. Two teardrops of blood dripped as ever from the knife that pierced the scarlet heart on her left thigh. Her tummy was flat and brown and the silver ring in her navel glinted in the bathroom spotlights. On her shoulder a butterfly tried to fly away, trapped for ever in the tattoo she had always regretted. She unwrapped her towel turban, releasing long almost-black hair that reached to her waist. She stared at her face in the mirror, wanting to scare away the look of serene calm that seemed to have settled upon her. She snapped off the light with the light pull, fled to the bedroom, pulling the top sheet on the bed right over her head, then after a minute or two emerged again to lie in semi-darkness wondering what the hell she was going to do.

There was nothing in the square, high-ceilinged studio flat, apart from the dress flung over the chair, to say that it was hers. It belonged to a friend of a friend of Annie’s, someone whose link with Manon was so tenuous she could not remember quite how the connection worked. In her mind, she pictured a family tree with wiggly lines instead of straight ones and gaps everywhere, but although she did not know him, she felt warmly towards the owner for allowing her to inhabit his space, and for getting her out of Annie’s flat where she had been staying after her return to England.

At the time, Annie had just bought her place in Notting Hill, and although she had made the offer of her spare room completely genuinely, Manon knew that she had not really wanted her there any more than Manon had wanted to be there. If that intuition had required confirmation, it had come later in the year when a running theme in the new series of Annie’s show was the central character’s struggle to get rid of a friend who outstays her welcome.

The owner of Manon’s studio was on an indefinite posting abroad and wanted someone who would be prepared to go at a moment’s notice but wouldn’t mess the place up, who would pay the bills and get in a plumber if the pipes froze, in return for living there on a peppercorn rent. Oddly, Manon seemed to be the only person like that around. When she had last been in England, she would have known hundreds of people who would have leapt at such an opportunity, but now she knew none. People in their thirties owned their homes, and anyone who desired a pied-a-terre in central London was so rich already that they could buy one and decorate it as they wished. When she had left the country, the people she had known were students, or recent postgraduates. Now they had second cars and secretaries, kitchens with extractor hoods over the oven and cappuccino machines, and, sometimes, children. She had nothing to show that she had existed in the intervening years except a few tattoos and a slim volume of short stories she had written. It was as if she had been in a time warp.

In the whitening light of dawn, Manon told herself that if you were going to bear a child, you needed to have done all that. It was a bit like the tables of conjugations and declensions in Latin that you had to learn before you could read Catullus. You could not have a baby without first doing the homework: finding somewhere permanent to live, a proper job, income and all of that took time. Her reason said it was impossible.

And yet part of her knew from seeing Saskia and Lily growing up that the only thing that children could not do without was a mother. For a second, she allowed herself to imagine introducing her baby to the little girls — bending down to their level, her arms cradling a bundle of cellular blanket, the wonder on their faces, and Lily’s delighted surprise when the baby’s tiny hand gripped her inquisitive finger.

The feeling of well-being that the image gave was seductive.

No. It was not possible. No.

On Monday, Manon decided, she would ring one of the numbers on the posters you saw on the tube escalators, the ones which euphemized the word abortion as advice. It would be quick. It was not a baby yet, she told herself, vaguely remembering the pictures of embryos that they had drawn for O level biology, comparing the size at the various stages to pieces of food, from

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher