![When You Were Here]()

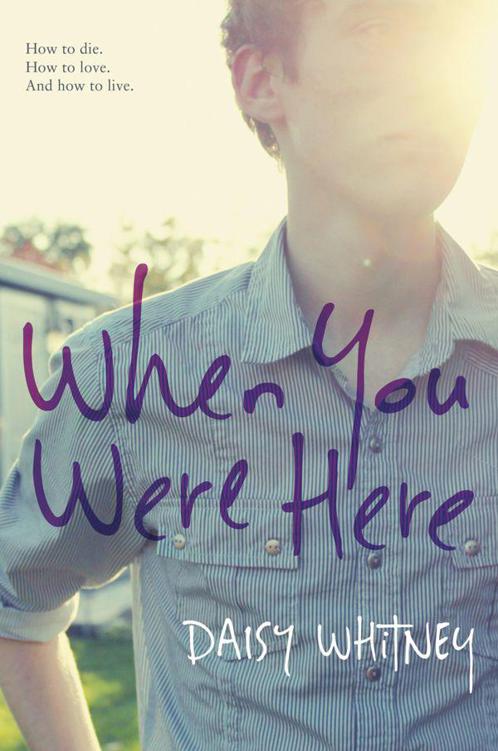

When You Were Here

Laini’s apology. Listening to her absent daughter say she messed up. Without having been there, without having heard it, I know what my mom would have said. That it was all good, and all fine, and there was nothing to worry about.

“I’m sure she hugged you and said she missed you and that she loved you,” I say quietly.

“Of course that’s what she said.”

I flash back to the card from Laini. It’s also in my wallet.

I feel a momentary sense of peace thinking about how Laini was finally able to say the important stuff to our mom before she died— I am glad you are my mom . That’s a gift,in a way, to be able to have the last thing you say to someone be the last thing you want them to have heard from you.

Now I have two answers for the price of one. Laini’s card and my dad’s note. But not just any card and not just any note. My mom kept those particular ones because of what they meant to her and for her. That card and that note mattered enough to travel around the world—good-luck charms maybe, talismans even—because they were the last things people she loved said to her. A promise— I will be back soon . Then starting over— I am glad you are my mom . Words of love. Words of happiness. No wonder my mom was happy. She knew how to hold on to what mattered, how to keep it close to her, how to let it heal her.

There’s a lull in the conversation, and Laini returns to her pigeon, taking a few more bites. “Do you know why I stay in China?”

“Because you’re Chinese?”

“Yes. And no. I came to China because I want it to be beautiful and healthy. Because I want to help the people. I’m glad now that my birth mom gave me up, but I want the families there to have a choice. This is how I make good for what I did to Mom. For how I left you both.”

I want to tell Laini it’s okay that she left, that she abandoned our mom when she needed her most. But I can’t exonerate her for that. I can’t absolve her for not being there. This forgiveness is not mine to give. It’s my mom’s, and she’s already given it. But we can move on. “Are you happy?In China? With Shen?” I ask, and place a hand on her back. This may be the first tender moment we’ve shared in years. The first real question I’ve asked her in ages.

She nods and wipes away a tear. “Yes. I am. I came to China because I wanted to feel connected to something again. And I stayed in China because it feels like home to me. It’s where I live now. It’s where I belong.”

I don’t think Laini and I are going to be best of friends. I doubt we’ll be the brother and sister who hang out and catch up each week over long, friendly phone calls. I suspect we’ll always be merely an item on the other’s to-do list. But I no longer want to smash her guitars.

At the very least I understand her now. Sometimes that’s enough.

Chapter Seventeen

When I return to my apartment, I head to my mom’s room. I flick on the light and walk to her bookshelves. There are envelopes on the lower shelf with photos, and framed pictures too. I pick up a framed photo of my mom and dad. She’s wearing a summer dress, and he’s in khakis and a blue button-down—standard-order over-forty male uniform, he called it, saying, I have no choice but to wear this, and someday, son, you’ll have to dress like this too . They’re standing by the pool at sunset. His arm is around her waist, and you can see that her hand is curled over his hand, their fingers interlaced. She’s smiling or laughing, maybe at something he said.

He always wanted to make us laugh. He used to take me out to the Santa Monica Pier for ice cream on Friday nights.We walked past the trapeze girls and the Ferris wheel and the skee ball to the ice-cream stand at the end of the pier. We’d stand there licking cones, watching the water, him joking about something or other, teasing me about school or making fun of himself.

“I turn forty-five soon. I think I’m going to have a midlife crisis,” he said over malted chocolate ice cream one night. “Should I get a sports car? Or a new stereo system?”

“A Ferrari. Get a Ferrari. Those are cool.”

“Sure. No problem. I hear the dealership is having a sale. Only two hundred and fifty thousand dollars.”

“They cost that much?”

“They don’t call it a midlife crisis for nothing, son,” he said.

But he wasn’t having a midlife crisis in the traditional way, because he was crazy about my mom. He liked to sneak kisses

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher