![When You Were Here]()

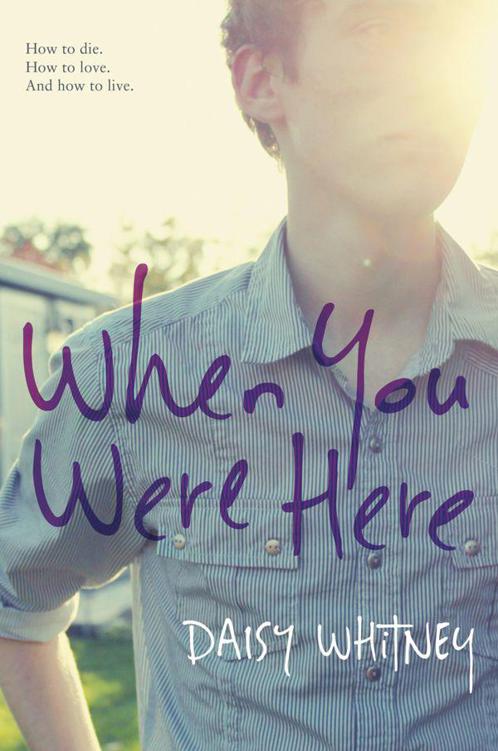

When You Were Here

through the quieter alleys, the small shops and the narrow lanes that lead in and out of gardens and temples and that bring me to a walking path that runs along a stream. Off to the side looms a narrow set of steps. After five minutes of going vertical, the stairs end at a stone bench that looks out over the gurgling water below. Laini sits on the bench. She stands, and for a second I think she is going to hug me.

Then we both remember—we don’t like each other.

Chapter Sixteen

We sit on opposite ends of the bench. Laini has packed a lunch, and for me she brings takeout sushi in a plastic container; for herself she has picked up pigeon lungs from a traditional Chinese restaurant.

“Shen and I go there every time we come to Kyoto,” she says, as if we regularly meet and chitchat about her travels and her life.

“Shen’s your boyfriend, I’m guessing?”

She nods and spears a piece of pigeon. “He’s writing about Eastern art, comparing Japanese to Chinese. So we come here every now and then. He’s spending the afternoon at the galleries and museums.”

“And this comparison, let me guess. I’m betting hethinks Chinese art is better.” I pop another piece of hamachi in my mouth.

She gives me a stern look. She really should have been a schoolteacher in the 1800s out on the Great Plains. She’d have done well, behind her glasses and with her hair pinned up. She chews the pigeon meat, and just the thought of eating a street rat makes me sick.

“Do you really like pigeon lungs?”

“Pigeons are delicious.” She offers me a chopstickful. I shake my head vehemently. “Have you ever had one?”

“No. I have never eaten pigeon, and I don’t ever plan on eating pigeon.”

“Then how do you know you don’t like it?”

“It’s a pigeon , Laini! You’re not supposed to eat it.”

“Just because you don’t like it doesn’t mean the rest of the world doesn’t like it. You can be so narrow-minded.”

“Yes. I’m narrow-minded. I’m closed off. That’s why I’m spending the summer five thousand miles away from my hometown.”

“Why are you spending the summer here, Danny?”

“ ’Cause the Tokyo Giants scouted me. They don’t mind that my shoulder is shot. They’ll let me pitch,” I say, and for some reason my joke elicits a laugh. Laini laughs with her whole mouth wide open. She has Kohler white teeth, perfectly straight, courtesy of two and a half years of Santa Monica’s best orthodontia. I take some strange solace in this; she is more American than she will let on. Then Ianswer her. I don’t tell her I came to Tokyo to figure out what to do with the apartment she doesn’t want or to learn all our mom’s secrets. But I don’t lie to her either. “I came to Tokyo because I like it. But I’ve always liked Tokyo, and you never did. That’s what I don’t understand. Because you hardly came home when Mom was sick, Laini, but you went there, and I just don’t get it. So what was it you said you had to tell Mom?”

She takes off her glasses and rubs the bridge of her nose. “Do you remember how I was to Mom before I left for college?”

“Remember? How could I forget? You were a complete bitch.”

She winces but takes it on the chin. “It wasn’t my finest moment. Or moments. But I didn’t realize it at the time.”

Laini has always been stubborn, has always dug in her heels. For her to admit she was wrong about something is nothing short of momentous. I let up on her a bit. “What do you mean, Laini?”

She reaches into her bag, a forest-green, woven, hippie-chick thing. She takes out a Moleskine notebook, unsnaps the elastic band that keeps it in place, and opens the notebook. Pressed between two sheets of paper is the ripped-off corner from a page in a spiral notebook. The jagged edge that completes the note my mom kept from my dad.

The missing piece.

Laini shows me the ripped paper, holding it gently in place with her index finger. “Do you see the date?”

I look down at the blue ink that matches the page that’s in my wallet now. One of my mom’s secrets; one of the clues. The note my dad wrote to her: L—I already miss you. I will be back soon. Love always.

“Of course. It’s the date Dad died,” I say, and, like invisible ink appearing, it clicks. That’s why my mom kept this note.

“He wrote her this note that day. She was reading it over and over again after he died. And when I saw the note, I just snapped.”

“Why?”

“Because it

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher