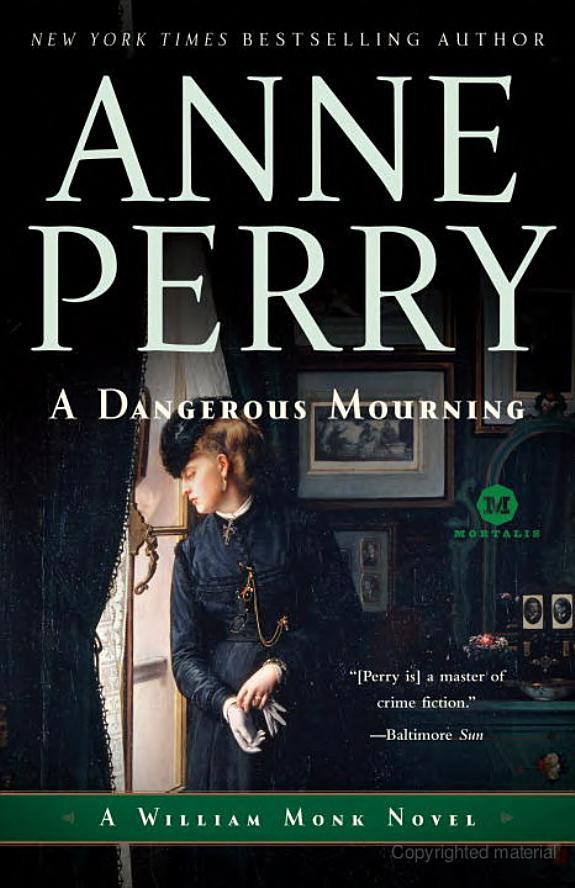

![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

as soon as he knew the cook had missed the knife.”

“Perhaps he intended to, but did not have the chance? What an agony of impotence for him. Can you imagine it?” O’Hare turned to the jury and raised his hands, palms upward. “What a rich irony! It was a man hoist with his own petard! And who would so richly deserve it?”

This time Rathbone rose and objected.

“My lord, Mr. O’Hare is assuming something which has yet to be proved. Even with all his well-vaunted gifts of persuasion, he has not so far shown us anything to indicate who put those objects in Percival’s room. He is arguing his conclusion from his premise, and his premise from his conclusion!”

“You will have to do better, Mr. O’Hare,” the judge cautioned.

“Oh, I will, my lord,” O’Hare promised. “You may be assured, I will!”

The second day O’Hare began with the physical evidence so dramatically discovered. He called Mrs. Boden, who took the stand looking homely and flustered, very much out of her element. She was used to being able to exercise her judgmentand her prodigious physical skills. Her art spoke for her. Now she was faced with standing motionless, every exchange to be verbal, and she was ill at ease.

When it was shown her, she looked at the knife with revulsion, but agreed that it was hers, from her kitchen. She recognized various nicks and scratches on the handle, and an irregularity in the blade. She knew the tools of her art. However she became severely rattled when Rathbone pressed her closely about exactly when she had last used it. He took her through the meals of each day, asking her which knives she had used in the preparation, and finally she became so confused he must have realized he was alienating the entire courtroom by pressing her over something for which no one else could see a purpose.

O’Hare rose, smiling and smooth, to call the ladies’ maid Mary to testify that the bloodstained peignoir was indeed Octavia’s. She looked very pale, her usually rich olive complexion without a shred of its blushing cheeks, her voice uncharacteristically subdued. But she swore it was her mistress’s. She had seen her wear it often enough, and ironed its satin and smoothed out its lace.

Rathbone did not bother her. There was nothing to contend.

Next O’Hare called the butler. Phillips looked positively cadaverous as he stepped into the witness box. His balding head shone in the light through his thin hair, his eyebrows appeared more ferocious than ever, but his expression was one of dignified wretchedness, a soldier on parade before an unruly mob and robbed of the weapons to defend himself.

O’Hare was far too practiced to insult him by discourtesy or condescension. After establishing Phillips’ position and his considerable credentials, he asked him about his seniority over the other servants in the house. This also established, for the jury and the crowd, he proceeded to draw him a highly unfavorable picture of Percival as a man, without ever impugning his abilities as a servant. Never once did he force Phillips into appearing malicious or negligent in his own duty. It was a masterly performance. There was almost nothing Rathbone could do except ask Phillips if he had had the slightest idea that this objectionable and arrogant young man had raised his eyes as far as his master’s daughter. To which Phillips repliedwith a horrified denial. But then no one would have expected him to admit such a thought—not now.

The only other servant O’Hare called was Rose.

She was dressed most becomingly. Black suited her, with her fair complexion and almost luminous blue eyes. The situation impressed her, but she was not overwhelmed, and her voice was steady and strong, crowded with emotion. With very little prompting she told O’Hare, who was oozing solicitude, how Percival had at first been friendly towards her, openly admiring but perfectly proper in his manner. Then gradually he had given her to believe his affections were engaged, and finally had made it quite plain that he desired to marry her.

All this she recounted with a modest manner and gentle tone. Then her chin hardened and she stood very rigid in the box; her voice darkened, thickening with emotion, and she told O’Hare, never looking at the jury or the spectators, how Percival’s attentions had ceased and he had more and more frequently mentioned Miss Octavia, and how she had complimented him, sent for him for the most trivial

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher