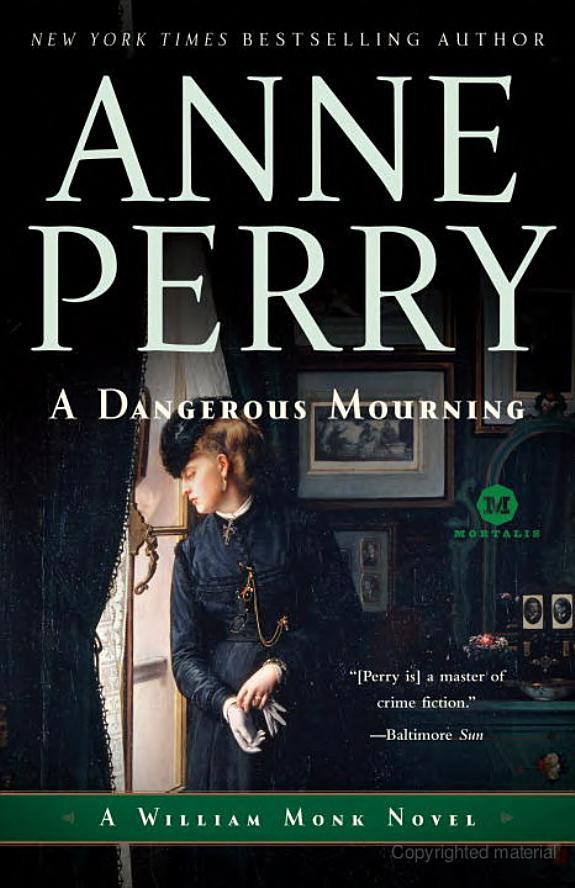

![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

been more time. The patrons also caught her attention, well-to-do men of business, rosy faced, well clothed against the winter chill, and most of all in obvious good spirits.

But Rathbone was welcomed by the host the moment they were through the door, and was immediately offered a table advantageously placed in a good corner and advised as to the specialty dishes of the day.

He consulted Hester as to her preference, then ordered, and the host himself set about seeing that only the best was provided. Rathbone accepted it as if it were pleasing, but no more than was his custom. He was gracious in his manner, but kept the appropriate distance between gentleman and innkeeper.

Over the meal, which was neither luncheon nor dinner, but was excellent, she told him the rest of the case in Queen Anne Street, so far as she knew it, including Myles Kellard’s attested rape of Martha Rivett and her subsequent dismissal, and more interestingly, her opinion of Beatrice’s emotions, her fear, which was obviously not removed by Percival’s arrest, and Septimus’s remarks that Octavia had said she heard something the afternoon before her death which was shocking and distressing, but of which she still lacked any proof.

She also told him of John Airdrie, Dr. Pomeroy and the loxa quinine.

By that time she had used an hour and a half of his time and he had used twenty-five minutes of hers, but she forgot to count it until she woke in the night in her room in Queen Anne Street.

“What do you advise me?” she said seriously, leaning a little across the table. “What can be done to prevent Percival being convicted without proper proof?”

“You have not said who is to defend him,” he replied with equal gravity.

“I don’t know. He has no money.”

“Naturally. If he had he would be suspect for that alone.” He smiled with a harsh twist. “I do occasionally take cases without payment, Miss Latterly, in the public good.” His smile broadened. “And recoup by charging exorbitantly next time I am employed by someone who can afford it. I will inquire into it and do what I can, give you my word.”

“I am very obliged to you,” she said, smiling in return. “Now would you be kind enough to tell me what I owe you for your counsel?”

“We agreed upon half a guinea, Miss Latterly.”

She opened her reticule and produced a gold half guinea, the last she had left, and offered it to him.

He took it with courteous thanks and slid it into his pocket.

He rose, pulled her chair out for her, and she left the coaching inn with an intense feeling of satisfaction quite unwarranted by the circumstances, and sailed out into the street for him to hail her a hansom and direct it back to Queen Anne Street.

The trial of Percival Garrod commenced in mid-January 1857, and since Beatrice Moidore was still suffering occasional moods of deep distress and anxiety, Hester was not yet released from caring for her. She complied with this arrangement eagerly, because she had not yet found other means of earning her living, but more importantly because it meant she could remain in the house at Queen Anne Street and observe the Moidore family. Not that she was aware of having learned anything helpful, but she never lost hope.

The whole family attended the trial at the Old Bailey. Basil had wished the women to remain at home and give their evidence in writing, but Araminta refused to consider obedienceto such an instruction, and on the rare occasions when she and Basil clashed, it was she who prevailed. Beatrice did not confront him on the issue; she simply dressed in quiet, unadorned black, heavily veiled, and gave Robert instructions to fetch her carriage. Hester offered to go with her as a matter of service, and was delighted when the offer was accepted.

Fenella Sandeman laughed at the very idea that she should forgo such a marvelously dramatic occasion, and swept out of the room, a little high on alcohol, wearing a long black silk kerchief and flinging it in the air with one white arm, delicately mittened in black lace.

Basil swore, but it was to no avail whatever. If she even heard him, it passed over her head harmlessly.

Romola refused to be the only one left at home, and no one bothered to argue with her.

The courtroom was crammed with spectators, and since this time Hester was not required to give any evidence, she was able to sit in the public gallery throughout.

The prosecution was conducted by a Mr. F. J. O’Hare, a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher