![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

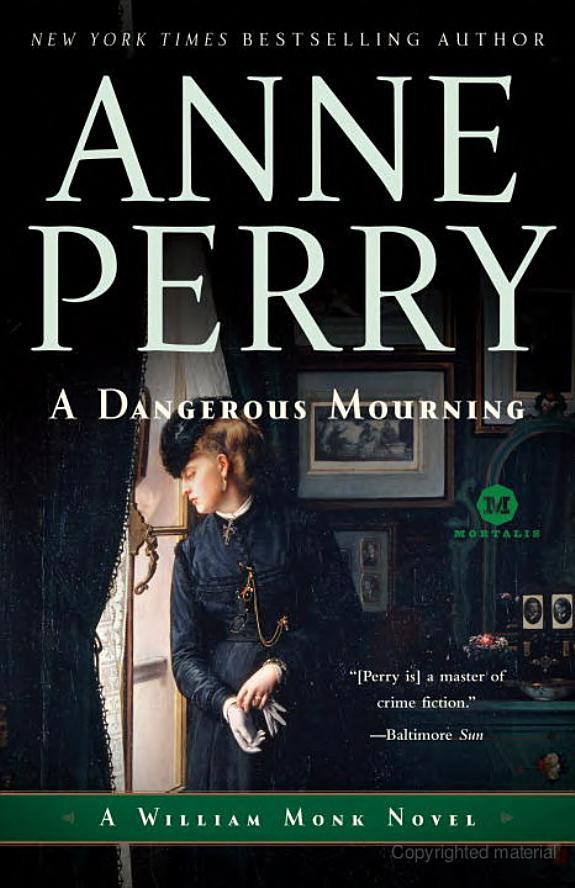

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

appalling she thought if she survived that, kept her sanity and some remnant of humor, then she would find anything in England a relief and encouragement. At least here there would be no cartloads of wounded, no raging epidemic fevers, no men brought in with frostbitten limbs to be amputated, or bodies frozen to death on the heights above Sebastopol. There would be ordinary dirt, lice and vermin, but nothing like the armies of rats that had hung on the walls and fallen like rotting fruit, the sounds of the fat bodies plopping on beds and floors sickening her dreams even now. And there would be the normal waste to clean, but not hospital floors running with poolsof excrement and blood from hundreds of men too ill to move, and rats, but not by the thousands.

But that horror had brought out the strength in her, as it had in so many other women. It was the endless pomposity, rule-bound, paper shuffling self-importance, and refusal to change that crippled her spirit now. The authorities regarded initiative as both arrogant and dangerous, and in women it was so totally misplaced as to be against nature.

The Queen might turn out to greet Florence Nightingale, but the medical establishment was not about to welcome young women with ideas of reform, and Hester had found this out through numerous infuriating, doomed confrontations.

It was all the more distressing because surgery had made such giant steps forward. It was ten years, to the month, since ether had been used successfully in America to anesthetize a patient during an operation. It was a marvelous discovery. Now all sorts of things could be done which had been impossible before. Of course a brilliant surgeon could amputate a limb; saw through flesh, arteries, muscle and bone; cauterize the stump and sew as necessary in a matter of forty or fifty seconds. Indeed Robert Liston, one of the fastest, had been known to saw through a thigh bone and amputate the leg, two of his assistant’s fingers, and the tail of an onlooker’s coat in twenty-nine seconds.

But the shock to the patient in such operations was appalling, and internal operations were out of the question because no one, with all the thongs and ropes in the world, could tie someone down securely enough for the knife to be wielded with any accuracy. Surgery had never been regarded as a calling of dignity or status. In fact, surgeons were coupled with barbers, more renowned for strong hands and speed of movement than for great knowledge.

Now, with anesthetic, all sorts of more complicated operations could be assayed, such as the removal of infected organs from patients diseased rather than wounded, frostbitten or gangrened; like this child she held in her arms, now close to sleep at last, his face flushed, his body curled around but eased to lie still.

She was holding him, rocking very gently, when Dr. Pomeroy came in. He was dressed for operating, in dark trousers, well worn and stained with blood, a shirt with a torn collar,and his usual waistcoat and old jacket, also badly soiled. It made little sense to ruin good clothes; any other surgeon would have worn much the same.

“Good morning, Dr. Pomeroy,” Hester said quickly. She caught his attention because she wished to press him to operate on this child within the next day or two, best of all this afternoon. She knew his chances of recovery were only very moderate—forty percent of surgical patients died of postoperative infection—but he would get no better as he was, and his pain was becoming worse, and therefore his condition weaker. She endeavored to be civil, which was difficult because although she knew his skill with the knife was high, she despised him personally.

“Good morning, Miss—er—eh—” He still managed to look surprised, in spite of the fact that she had been there a month and they had conversed frequently, most often with opposing views. They were not exchanges he was likely to forget. But he did not approve of nurses who spoke before they were addressed, and it caught him awry every time.

“Latterly,” she supplied, and forbore from adding, “I have not changed it since yesterday—nor indeed at all,” which was on the edge of her tongue. She cared more about the child.

“Yes, Miss Latterly, what is it?” He did not look at her, but at the old woman on the bed opposite, who was lying on her back with her mouth open.

“John Airdrie is in considerable pain, and his condition is not improving,” she said with

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher