![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

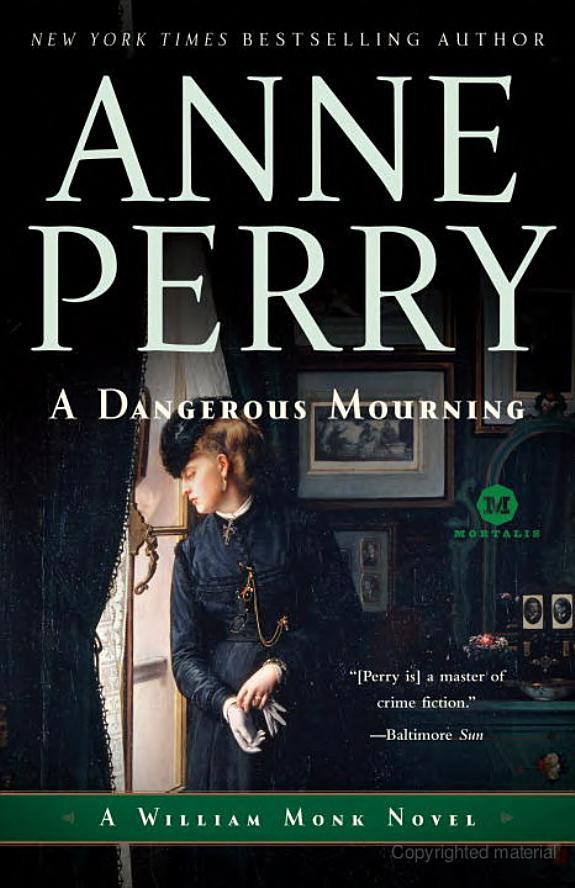

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

late for genteel afternoon calling, and far too early for dinner. Hester waited expectantly.

“Menard Grey comes to trial the day after tomorrow,” Callandra said quietly. “We must testify on his behalf—I presume you are still willing?”

“Of course!” There was not even a second’s doubt.

“Then we had better go and meet with the lawyer I have employed to conduct his defense. He will have some counsel for us concerning our testimony. I have arranged to see him in his rooms this evening. I am sorry it is so hasty, but he is extremely busy and had no other opportunity. We may have dinner first, or later, as you please. My carriage will return in half an hour; I thought it unsuitable to leave it outside.” She smiled wryly; explanation was not necessary.

“Of course.” Hester sank deeper into her chair and thought of Mrs. Home’s cup of tea. She would have that well beforeshe thought of changing her clothes, putting her boots on again, and traipsing out to see some lawyer.

But Oliver Rathbone was not “some lawyer”; he was the most brilliant advocate practicing at the bar, and he knew it. He was a lean man of no more than average height, neatly but unremarkably dressed, until one looked closely and saw the quality of the fabric and, after a little while, the excellence of the cut, which fitted him perfectly and seemed always to hang without strain or crease. His hair was fair and his face narrow with a long nose and a sensitive, beautifully shaped mouth. But the overriding impression was one of controlled emotion and brilliant, all-pervading intelligence.

His rooms were quiet and full of light from the chandelier which hung from the center of an ornately plastered ceiling. In the daylight they would have been equally well illuminated by three large sash windows, curtained in dark green velvet and bound by simple cords. The desk was mahogany and the chairs appeared extremely comfortable.

He ushered them in and bade them be seated. At first Hester was unimpressed, finding him a little too concerned for their ease than for the purpose of their visit, but this misapprehension vanished as soon as he addressed the matter of the trial. His voice was pleasing enough, but the preciseness of his diction made it memorable so that even his exact intonation remained with her long afterwards.

“Now, Miss Latterly,” he said, “we must discuss the testimony you are to give. You understand it will not simply be a matter of reciting what you know and then being permitted to leave?”

She had not considered it, and when she did now, that was precisely what she had assumed. She was about to deny it, and saw in his face that he had read her thoughts, so she changed them.

“I was awaiting your instructions, Mr. Rathbone. I had not judged the matter one way or the other.”

He smiled, a delicate, charming movement of the lips.

“Quite so.” He leaned against the edge of his desk and regarded her gravely. “I will question you first. You are my witness, you understand? I shall ask you to tell the events of your family’s tragedy, simply, from your own point of view. I do not wish you to tell me anything that you did not experienceyourself. If you do, the judge will instruct the jury to disregard it, and every time he stops you and disallows what you say, the less credence the jury will give to what remains. They may easily forget which is which.”

“I understand,” she assured him. “I will say only what I know for myself.”

“You may easily be tempted, Miss Latterly. It is a matter in which your feelings must be very deep.” He looked at her with brilliant, humorous eyes. “It will not be as simple as you may expect.”

“What chance is there that Menard Grey will not be hanged?” she asked gravely. She chose deliberately the harshest words. Rathbone was not a man with whom to use euphemisms.

“We will do the best we can,” he replied, the light fading from his face. “But I am not at all sure that we will succeed.”

“And what would be success, Mr. Rathbone?”

“Success? Success would be transportation to Australia, where he would have some chance to make a new life for himself—in time. But they stopped most transportation three years ago, except for cases warranting sentences over fourteen years—” He paused.

“And failure?” she said almost under her breath. “Hanging?”

“No,” he said, leaning forward a little. “The rest of his life somewhere like the Coldbath

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher