![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

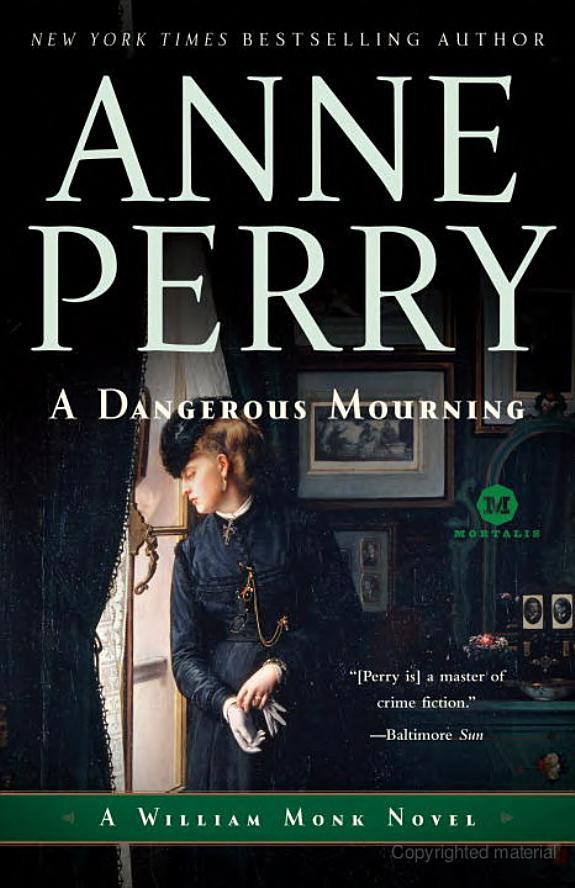

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

fireworks, the laughter, the great gowns and the music and fine horses. Once as a child she had been presented to the Iron Duke himself. She recalled it with a smile and a faraway look of almost forgotten pleasure.

Then she spoke of the death of the old king, William IV, and the accession of the young Victoria. The coronation had been splendid beyond imagination. Beatrice had been in the prime of her beauty then, and without conceit she told of the celebrations she and Basil had attended, and how she had been admired.

Luncheon came and went, and tea also, and still she foughtoff reality with increasing fierceness, the color heightening in her cheeks, her eyes more feverish.

If anyone missed them, they made no sign of it, nor came to seek them.

It was half past four, and already dark, when there was a knock on the door.

Beatrice was ashen white. She looked at Hester once, then with a massive effort said quite levelly, “Come in.”

Cyprian came in, his face furrowed with anxiety and puzzlement, not yet fear.

“Mama, the police are here again, not that fellow Monk, but Sergeant Evan and a constable—and that wretched lawyer who defended Percival.”

Beatrice rose to her feet; only for a moment did she sway.

“I will come down.”

“I am afraid they do wish to speak to all of us, and they refuse to say why. I suppose we had better oblige them, although I cannot think what it can be about now.”

“I am afraid, my dear, that it is going to be extremely unpleasant.”

“Why? What can there be left to say?”

“A great deal,” she replied, and took his arm so that he might support her along the corridor and down the stairs to the withdrawing room, where everyone else was assembled, including Septimus and Fenella. Standing in the doorway were Evan and a uniformed constable. In the middle of the floor was Oliver Rathbone.

“Good afternoon, Lady Moidore,” he said gravely. In the circumstances it was a ridiculous form of greeting.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Rathbone,” she answered with a slight quiver in her voice. “I imagine you have come to ask me about the peignoir?”

“I have,” he said quietly. “I regret that I must do this, but there is no alternative. The footman Harold has permitted me to examine the carpet in the study—” He stopped, and his eyes wandered around the assembled faces. No one moved or spoke.

“I have discovered the bloodstains on the carpet and on the handle of the paper knife.” Elegantly he slid the knife out of his pocket and held it, turning it very slowly so its blade caught the light.

Myles Kellard stood motionless, his brows drawn down in disbelief.

Cyprian looked profoundly unhappy.

Basil stared without blinking.

Araminta clenched her hands so hard the knuckles showed, and her skin was as white as paper.

“I suppose there is some purpose to this?” Romola said irritably. “I hate melodrama. Please explain yourself and stop play-acting.”

“Oh be quiet!” Fenella snapped. “You hate anything that isn’t comfortable and decently domestic. If you can’t say something useful, hold your tongue.”

“Octavia Haslett died in the study,” Rathbone said with a level, careful voice that carried above every other rustle or murmur in the room.

“Good God!” Fenella was incredulous and almost amused. “You don’t mean Octavia had an assignation with the footman on the study carpet. How totally absurd—and uncomfortable, when she has a perfectly good bed.”

Beatrice swung around and slapped her so hard Fenella fell over sideways and collapsed into one of the armchairs.

“I’ve wanted to do that for years,” Beatrice said with intense satisfaction. “That is probably the only thing that will give me any pleasure at all today. No—you fool. There was no assignation. Octavia discovered how Basil had Harry set at the head of the charge of Balaclava, where so many died, and she felt as trapped and defeated as we all do. She took her own life.”

There was an appalled silence until Basil stepped forward, his face gray, his hand shaking. He made a supreme effort.

“That is quite untrue. You are unhinged with grief. Please go to your room, and I shall send for the doctor. For heaven’s sake, Miss Latterly, don’t stand there, do something!”

“It is true, Sir Basil.” She stared at him levelly, for the first time not as a nurse to her employer but as an equal. “I went to the War Office myself, and learned what happened to Harry Haslett,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher