![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

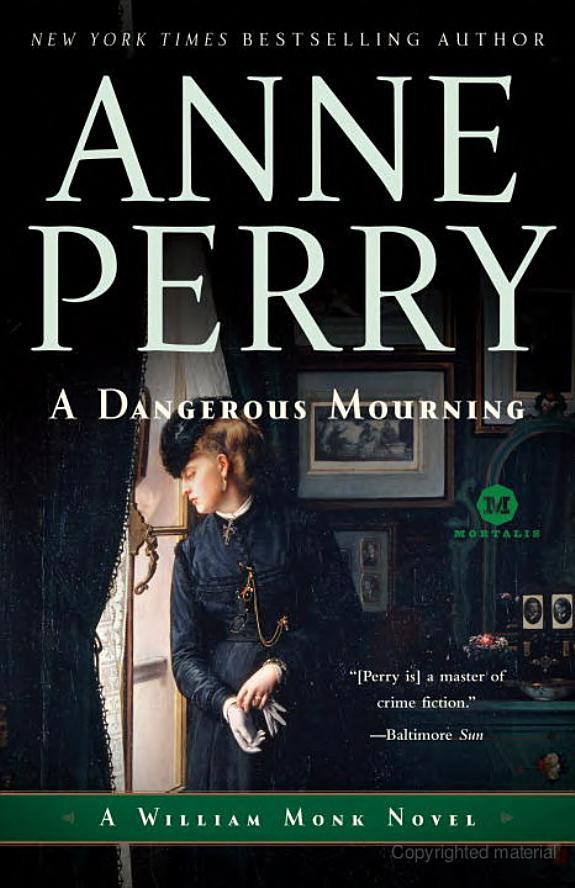

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

the laundry. You didn’t just shove the clothes in a washing machine. There was a specific recipe for the type of cloth, and you had to make your own soap depending on the fabric. Then you had to hope the laundry would dry, which was not easy on a wet day, and you had to iron with two flat irons—use one while the other heated up on the stove. It took the whole day! This all set you back immediately.

On the other hand, there used to be four postal deliveries a day in London, so not everything today is better. You could invite an acquaintance to dinner by post in the morning and receive an answer in the afternoon mail. It was a wealthy society in which there was plenty of leisure time, which led to more rules to divide the up-and-coming from the not-so-good.

M: Don’t you think the ritual of calling hours would have driven you crazy?

AP: If I had been part of it, I suppose I would have known. I wouldn’t fit in remotely in Victorian society; I’d demand to be treated as an equal, not as lesser because I am a woman.

M: You would have been like Hester Latterly, then?

AP: I would like to think I would, if I had the courage Hester had. My brother is a doctor, an army surgeon. I have some skills in that arena but not like him. Whether I would have the guts for that sort of work, I doubt it.

M: You’ve written previously that

The Divine Comedy, Gilgamesh

, and the works of Oscar Wilde are among your favorite books; that’s a varied reading list. Are there any other books or authors that have had an important impact on your career?

AP: G. K. Chesterton. He is my favorite poet.

M: Do you like his Father Brown mysteries?

AP: Father Brown is a bit dated. It’s Chesterton’s poetry that I love: the music of it, the passion, the lyricism, but most of all his philosophy. I am still surprised when I read it and am made to think. When I’m reading for pleasure, I want a complete holiday from what I’m doing myself. In terms of present-day authors, there is nobody better than Michael Connolly, Jeffery Deaver, and Robert Crais.

M: All fellow mystery writers—how is that a complete holiday for you?

AP: They write about the present day, in cities like Los Angeles, with male protagonists, all of which is pretty different from Victorian London. Also, I think books written by men have a different flavor. Though I hope one wouldn’t know immediately whether my books were written by a man or a woman.

M: Were you influenced by any of the other great detectives in literature, such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, or Agatha Christie’s sleuths?

AP: Not Agatha Christie. Dorothy L. Sayers was good. Holmes is iconic in lots of ways, and the stories are better than they are often given credit for, especially in the complex relationship between Holmes and Watson. Watson was a lot sharper than he’s been portrayed in the films; he was not an idiot at all, and more mentally well balanced than Holmes, who was erratic.

M: Tell us a little bit about William Monk, and what he means to you.

AP: I start him off waking up in hospital after an accident, and he knows nothing about himself at all. He sees his face in a mirror and it means nothing to him, and he has to discover who he is by detection. He’s lying there in his hospital bed when a nurse says, “The police want to see you,” and when they come in, it’s obvious Monk is a policeman, and the visitor is his boss who doesn’t like him and is only too ready to catch him in a mistake. When Monk is well enough to leave the hospital, he is assigned a rotten case and has to discover who committed an appalling crime, while at the same time trying to discover who are his own friends and enemies. It’s a hell of a thing to find out the two at once. The more Monk pursues both threads, the more he experiences flashes of memory and feels he’s finding out not only about the case, but about himself. There’s evidence indicating that he’s been at the crime scene before, and yet he can’t remember it.

M: You’ve called Monk a darker character than your other creations.

AP: Yes, he is, because he wasn’t a particularly nice person before his accident. If I had to discover myself through the eyes of others, I wouldn’t like that, would you? You know what you did, but not why. We all have reasonable excuses for our actions that we can live with at the time, but viewed at a distance by someone else it becomes quite difficult.

The evidence is there, I did this,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher