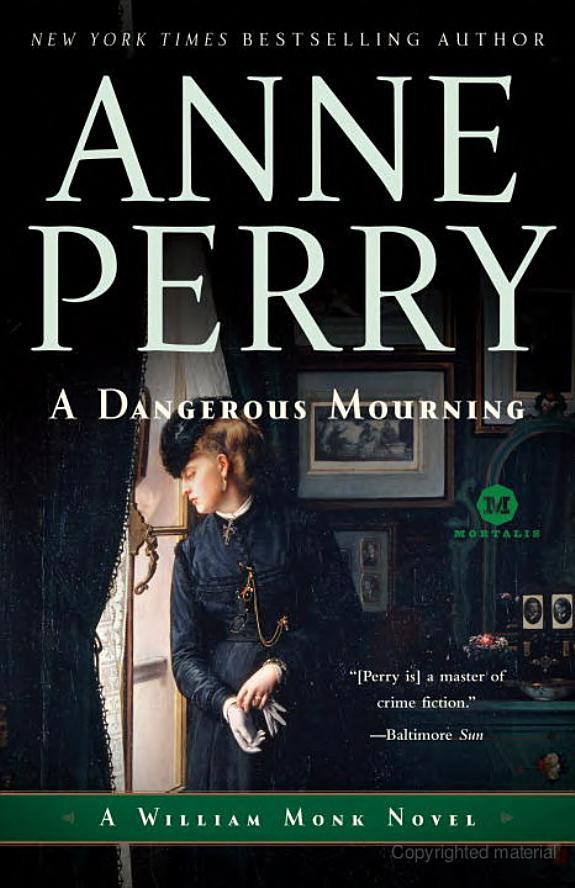

![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

before, Miss Latterly.” His voice was heavy with sarcasm. “Even occasionally in cases of considerable importance. I am aware of the procedure.”

She was annoyed with herself for having left herself open to such a remark, and with him for making it. Instinctively she dealt back the hardest blow that she could.

“I see a great deal of your recollection must have returned since we last met. I had not realized, or of course I should not have commented. I was endeavoring to be helpful, but it seems you do not require it.”

The color drained from his face leaving two bright spots ofpink on his cheekbones. His mind was racing for an equal barb to return.

“I have forgotten much, Miss Latterly, but that still leaves me with an advantage over those who never knew anything in the beginning!” he said tartly, turning away.

Callandra smiled and did not interfere.

“It was not my assistance I was suggesting, Mr. Monk,” Hester snapped back. “It was Mr. Rathbone’s. But if you believe you know better than he does, I can only hope you are right and indeed you do—not for your sake, which is immaterial, but for Menard Grey’s. I trust you have not lost sight of our purpose in being here?”

She had won that exchange, and she knew it.

“Of course I haven’t,” he said coldly, standing with his back to her, hands in his pockets. “I have left my present investigation to Sergeant Evan and come early in case Mr. Rathbone wished to see me, but I have no intention of disturbing him if he does not.”

“He may not know you are here to be seen,” she argued.

He turned around to face her. “Miss Latterly, can you not for one moment refrain from meddling in other people’s affairs and assume we are capable of managing without your direction? I informed his clerk as I came in.”

“Then all civility required you do was say so when I asked you!” she replied, stung by the charge of interfering, which was totally unjust—or anyway largely—or to some extent! “But you do not seem to be capable of ordinary civility.”

“You are not an ordinary person, Miss Latterly.” His eyes were very wide, his face tight. “You are overbearing, dictatorial, and seem bent to treat everyone as if they were incapable of managing without your instruction. You combine the worst elements of a governess with the ruthlessness of a workhouse matron. You should have stayed in the army—you are eminently suited for it.”

That was the perfect thrust; he knew how she despised the army command for its sheer arrogant incompetence, which had driven so many men to needless and appalling deaths. She was so furious she choked for words.

“I am not,” she gasped. “The army is made up of men—and those in command of it are mostly stubborn and stupidlike you. They haven’t the faintest idea what they are doing,but they would rather blunder along, no matter who is killed by it, than admit their ignorance and accept help.” She drew breath again and went on. “They would rather die than take counsel from a woman—which in itself wouldn’t matter a toss. It’s their letting other people die that is unforgivable.”

He was prevented from having to think of a reply by the bailiff coming to the door and requesting Hester to prepare herself to enter the courtroom. She rose with great dignity and swept out past him, catching her skirt in the doorway and having to stop and tweak it out, which was most irksome. She flashed a smile at Callandra over her other shoulder, then with fluttering stomach followed the bailiff along the passageway and into the court.

The chamber was large, high ceilinged, paneled in wood and so crowded with people they seemed to press in on her from every side. She could feel a heat from their bodies as they jostled and craned to see her come in, and there was a rustle and hiss of breath and a shuffle of feet as people fought to maintain balance. In the press benches pencils flew, scratching notes on paper, making outlines of faces and hats.

She stared straight ahead and walked up the cleared way to the witness box, angry that her legs were trembling. She stumbled on the step, and the bailiff put out his hand to steady her. She looked around for Oliver Rathbone, and saw him immediately, but with his white lawyer’s wig on he looked different, very remote. He regarded her with the distant politeness he would a stranger, and it was surprisingly chilling.

She could hardly feel worse. There was nothing to be

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher