![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

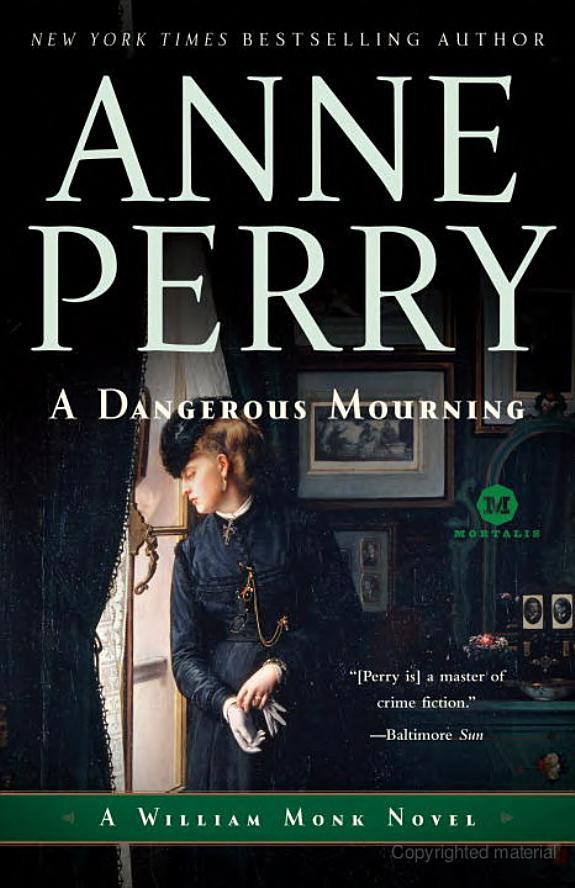

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

mind, his quick, cruel wit. It was an unpleasant thought, and it took the warmth out of his feeling of superiority. He had almost certainly contributed to what the man had become. That Runcorn had always been weak, vain, less able, was a thin excuse, and any honesty at all evaporated it. Themore flawed a man was, the shoddier it was to take advantage of his inadequacies to destroy him. If the strong were irresponsible and self-serving, what could the weak hope for?

Monk went to bed early and lay awake staring at the ceiling, disgusted with himself.

The funeral of Octavia Haslett was attended by half the aristocracy in London. The carriages stretched up and down Langham Place, stopping the normal traffic, black horses whenever possible, black plumes tossing, coachmen and footmen in livery, black crepe fluttering, harnesses polished like mirrors, but not a single piece that jingled or made a sound. An ambitious person might have recognized the crests of many noble families, not only of Britain but of France and the states of Germany as well. The mourners wore black, immaculate, devastatingly fashionable, enormous skirts hooped and petticoated, ribboned bonnets, gleaming top hats and polished boots.

Everything was done in silence, muffled hooves, well-oiled heels, whispering voices. The few passersby slowed down and bowed their heads in respect.

From his position like a waiting servant on the steps of All Saints Church, Monk saw the family arrive, first Sir Basil Moidore with his remaining daughter, Araminta, not even a black veil able to hide the blazing color of her hair or the whiteness of her face. They climbed the steps together, she holding his arm, although she seemed to support him as much as he her.

Next came Beatrice Moidore, very definitely upheld by Cyprian. She walked uprightly, but was so heavily veiled no expression was visible, but her back and shoulders were stiff and twice she stumbled and he helped her gently, speaking with his head close to hers.

Some distance behind, having come in a separate carriage, Myles Kellard and Romola Moidore came side by side, but not seeming to offer each other anything more than a formal accompaniment. Romola moved as if she was tired; her step was heavy and her shoulders a little bowed. She too wore a veil so her face was invisible. A few feet to her right Myles Kellard looked bleak, or perhaps it was boredom. He climbed the steps slowly, almost absently, and only when they reachedthe top did he offer her a hand at her elbow, more as a courtesy than a support.

Lastly came Fenella Sandeman in overdramatic black, a hat with too much decoration on it for a funeral, but undoubtedly handsome. Her waist was nipped in so she looked fragile, at a few yards’ distance giving an impression of girlishness, then as she came closer one saw the too-dark hair and the faint withering of the skin. Monk did not know whether to pity her ridiculousness or admire her bravado.

Close behind her, and murmuring to her every now and again, was Septimus Thirsk. The hard gray daylight showed the weariness in his face and his sense of having been beaten, finding his moments of happiness in very small victories, the great ones having long ago been abandoned.

Monk did not go inside the church yet, but waited while the reverent, the grieving and the envious made their way past him. He overheard snatches of conversation, expressions of pity, but far more of outrage. What was the world coming to? Where was the much vaunted new Metropolitan Police Force while all this was going on? What was the purpose in paying to have them if people like the Moidores could be murdered in their own beds? One must speak to the Home Secretary and demand something be done!

Monk could imagine the outrage, the fear and the excuses that would take place over the next days or weeks. Whitehall would be spurred by complaints. Explanations would be offered, polite refusals given, and then when their lordships had left, Runcorn would be sent for and reports requested with icy disfavor hiding a hot panic.

And Runcorn would break out in a sweat of humiliation and anxiety. He hated failure and had no idea how to stand his ground. And he in turn would pass on his fears, disguised as official anger, to Monk.

Basil Moidore would be at the beginning of the chain—and at the end, when Monk returned to his house to tear apart the comfort and safe beliefs of his family, all their assumptions about one another and the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher