![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

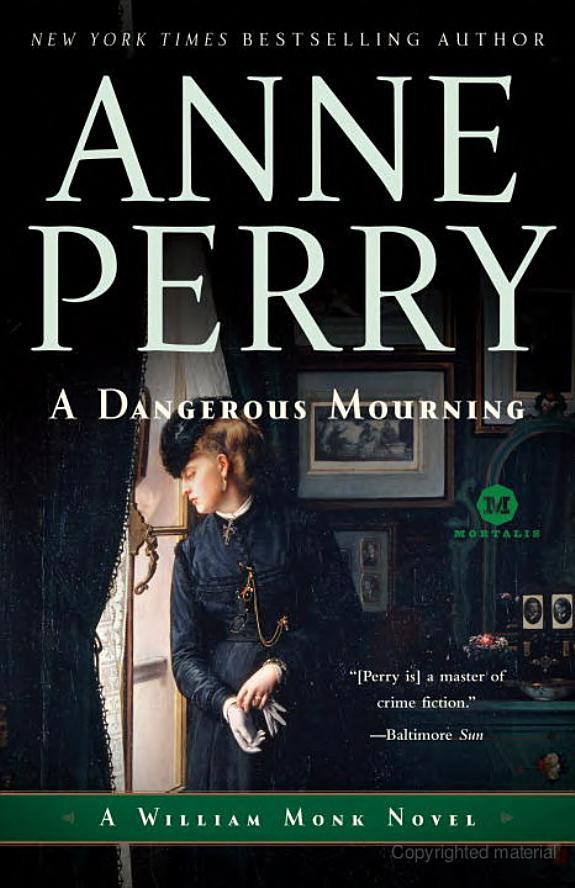

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

explained. “But I think downstairs emotions concern others downstairs.”

“What about if Mrs. Haslett knew something about them, some past sin of thieving or immorality?” Monk suggested. “That would lose them a very comfortable position. Without references they’d not get another—and a servant who can’t get a place has nowhere to go but the sweatshops or the street.”

“Could be,” Evan agreed. “Or the footmen. There are two—Harold and Percival. Both seem fairly ordinary so far. I should say Percival is the more intelligent, and perhaps ambitious.”

“What does a footman aspire to be?” Monk said a little waspishly.

“A butler, I imagine,” Evan replied with a faint smile. “Don’t look like that, sir. Butler is a comfortable, responsible and very respected position. Butlers consider themselves socially far superior to the police. They live in fine houses, eat the best, and drink it. I’ve seen butlers who drink better claret than their masters—”

“Do their masters know that?”

“Some masters don’t have the palate to know claret from cooking wine.” Evan shrugged. “All the same, it’s a little kingdom that many men would find most attractive.”

Monk raised his eyebrows sarcastically. “And how would knifing the master’s daughter get him any closer to this enjoyable position?”

“It wouldn’t—unless she knew something about him that would get him dismissed without a reference.”

That was plausible, and Monk knew it.

“Then you had better go back and see what you can learn,” he directed. “I’m going to speak to the family again, which I still think, unfortunately, is far more likely. I want to see them alone, away from Sir Basil.” His face tightened. “He orchestrated the last time as if I had hardly been there.”

“Master in his house.” Evan hitched himself off the windowsill. “You can hardly be surprised.”

“That is why I intend to see them away from Queen Anne Street, if I can,” Monk replied tersely. “I daresay it will take me all week.”

Evan rolled his eyes upward briefly, and without speaking again went out; Monk heard his footsteps down the stairs.

It did take Monk most of the week. He began straightaway with great success, almost immediately finding Romola Moidore walking in a leisurely fashion in Green Park. She started along the grass parallel with Constitution Row, gazing at the trees beyond by Buckingham Palace. The footman Percival had informed Monk she would be there, having ridden in the carriage with Mr. Cyprian, who was taking luncheon at his club in nearby Piccadilly.

She was expecting to meet a Mrs. Ketteridge, but Monk caught up with her while she was still alone. She was dressed entirely in black, as befitted a woman whose family was in mourning, but she still looked extremely smart. Her wide skirts were tiered and trimmed with velvet, the pergola sleeves of her dress were lined with black silk, her bonnet was small and worn low on the back of the head, and her hair was in the very fashionable style turned under at the ears into a lowset knot.

She was startled to see him, and not at all pleased. However there was nowhere for her to go to avoid him without being obvious, and perhaps she bore in mind her father-in-law’s strictures that they were all to be helpful. He had not said so in so many words in Monk’s hearing, but his implication was obvious.

“Good morning, Mr. Monk,” she said coolly, standing quite still and facing him as if he were a stray dog that had approached too close and should be warded off with the fringedumbrella which she held firmly in her right hand, its point a little above the ground, ready to jab at him.

“Good morning, Mrs. Moidore,” he replied, inclining his head a little in politeness.

“I really don’t know anything of use to you.” She tried to avoid the issue even now, as if he might go away. “I have no idea at all what can have happened. I still think you must have made a mistake—or been misled—”

“Were you fond of your sister-in-law, Mrs. Moidore?” he asked conversationally.

She tried to remain facing him, then decided she might as well walk, since it seemed he was determined to. She resented promenading with a policeman, as though he were a social acquaintance, and it showed in her face; although no one else would have known his station, certainly his clothes were almost as well cut and as fashionable as hers, and his bearing every bit as

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher