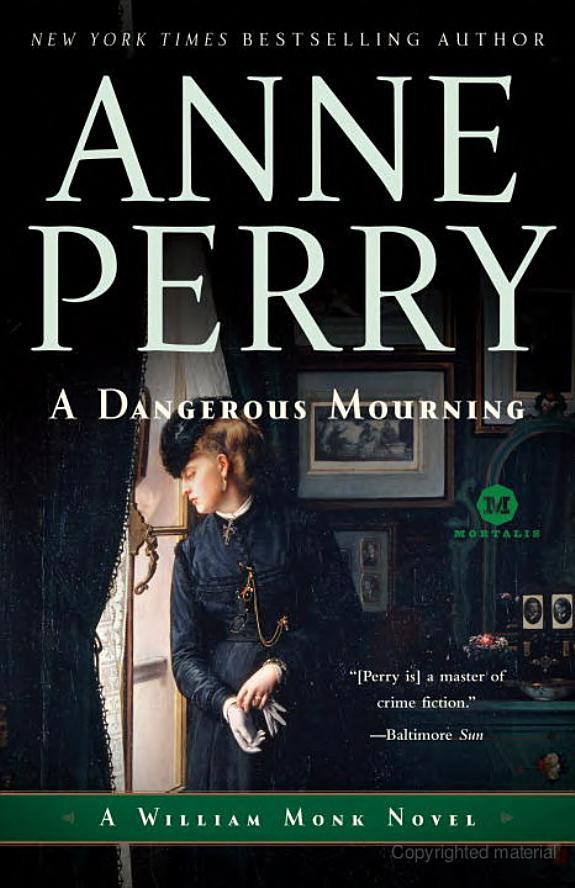

![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

concentration.

“She gave something to that child at the end when he had a fever after his operation,” he said clearly. “He was in a bad way, like to go into delirium. And after she did it four or five times he recovered. He’s cool as you like now. She knows what she’s doing—she’s right.”

There was a moment’s awful silence. He had no idea what he had done.

Pomeroy was stunned.

“You gave loxa quinine to John Airdrie!” he accused, realization flooding into him. “You did it behind my back!” His voice rose, shrill with outrage and betrayal, not only by her but, even worse, by the patient.

Then a new thought struck him.

“Where did you get it from? Answer me, Miss Latterly! I demand you tell me where you obtained it! Did you have the audacity to send to the fever hospital in my name?”

“No, Dr. Pomeroy. I have some quinine of my own—a very small amount,” she added hastily, “against fever. I gave him some of that.”

He was trembling with rage. “You are dismissed, Miss Latterly. You have been a troublemaker since you arrived. You were employed on the recommendation of a lady who no doubtowed some favor to your family and had little knowledge of your irresponsible and willful nature. You will leave this establishment today! Whatever possessions you have here, take them with you. And there is no purpose in your asking for a recommendation. I can give you none!”

There was silence in the ward. Someone rustled bedclothes.

“But she cured the boy!” the patient protested. “She was right! ’e’s alive because of ’er!” The man’s voice was thick with distress, at last understanding what he had done. He looked at Pomeroy, then at Hester. “She was right!” he said again.

Hester could at last afford the luxury of ceasing to care in the slightest what Pomeroy thought of her. She had nothing to lose now.

“Of course I shall go,” she acknowledged. “But don’t let your pride prevent you from helping Mrs. Begley. She doesn’t deserve to die to save your face because a nurse told you what to do.” She took a deep breath. “And since everyone in this room is aware of it, you will find it difficult to excuse.”

“Why you—you—!” Pomeroy spluttered, scarlet in the face but lost for words violent enough to satisfy his outrage and at the same time not expose his weakness. “You—”

Hester gave him one withering look, then turned away and went over to the patient who had defended her, now sitting with the bedclothes in a heap around him and a pale face full of shame.

“There is no need to blame yourself,” she said to him very gently, but clearly enough for everyone else in the ward to hear her. He needed his excusing to be known. “It was bound to happen that one day I should fall out with Dr. Pomeroy sufficiently for this to happen. At least you have spoken up for what you know, and perhaps you will have saved Mrs. Begley a great deal of pain, maybe even her life. Please do not criticize yourself for it or feel you have done me a disfavor. You have done no more than choose the time for what was inevitable.”

“Are you sure, miss? I feel that badly!” He looked at her anxiously, searching her face for belief.

“Of course I’m sure.” She forced herself to smile at him. “Have you not watched me long enough to judge that for yourself? Dr. Pomeroy and I have been on a course that was destined for collision from the beginning. And it was never possible that I should have the better of it.” She began tostraighten the sheet around him. “Now take care of yourself—and may God heal you!” She took his hand briefly, then moved away again. “In spite of Pomeroy,” she added under her breath.

When she had reached her rooms, and the heat of temper had worn off a little, she began to realize what she had done. She was not only without an occupation to fill her time, and financial means with which to support herself, she had also betrayed Callandra Daviot’s confidence in her and the recommendation to which she had given her name.

She had a late-afternoon meal alone, eating only because she did not want to offend her landlady. It tasted of nothing. By five o’clock it was growing dark, and after the gas lamps were lit and the curtains were drawn the room seemed to narrow and close her in in enforced idleness and complete isolation. What should she do tomorrow? There was no infirmary, no patients to care for. She was completely unnecessary and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher