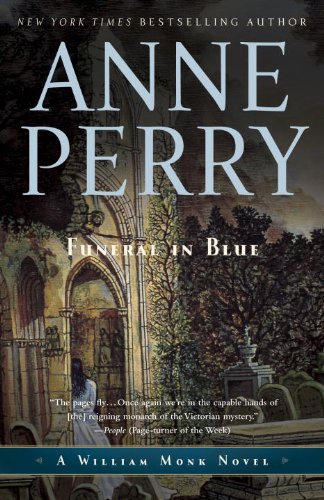

![William Monk 12 - Funeral in Blue]()

William Monk 12 - Funeral in Blue

I won’t sell it.”

“Why Germany?”

“What?” He looked at the painting, his face filled with grief. “It’s Vienna,” he corrected flatly. “The Austrians speak German.”

“Why Vienna?”

“Things she told me, in her past.” He looked up at Monk. “What has that got to do with whoever killed her?”

“I don’t know. Why were you so long painting the portrait her father commissioned?”

“He was in no hurry.”

“Apparently neither were you. No need to get paid?” Monk allowed his voice a slight edge of sarcasm.

Allardyce’s eyes blazed for a moment. “I’m an artist, not a journeyman,” he retorted. “As long as I can buy paints and canvas, money is unimportant.”

“Really,” Monk said without expression. “But I assume you would take Pendreigh’s money when the picture was completed?”

“Of course! I need to eat . . . and pay the rent.”

“And

Funeral in Blue

, would you sell that?”

“No! I told you I wouldn’t.” His face pinched and the aggression in him melted away. “I won’t sell that.” He did not feel any need to justify himself. His grief was his own, and he did not care whether Monk understood it or not.

“How many pictures of her did you paint?” Monk asked, watching the anger and misery in his face.

“Elissa? Five or six. Some of them were just sketches.” He looked back at Monk, narrowing his eyes. “Why? What does it matter now? If you think I killed her, you’re a fool. No artist destroys his inspiration.” He did not bother to explain, either because he thought Monk incapable of understanding or because he simply did not care.

Monk looked across at Runcorn and saw the struggle for comprehension in his face. He was foundering in an unfamiliar world, afraid even to try to find his way. Everything about it was different from what he was accustomed to. It offended his rigid upbringing and the rules he had been taught to believe. The immorality of it confused him, and yet he was beginning to realize that it also had standards of a sort, passions, vulnerabilities and dreams.

The moment he was aware of Monk’s scrutiny he froze, wiping his expression blank. “Learned anything?” he said curtly.

“Possibly,” Monk answered. He pulled out his pocket watch. It was nearly seven o’clock.

“In a hurry?” Runcorn asked.

“I was thinking about Dr. Beck.” Monk replaced the watch.

“Tomorrow,” Runcorn said. He turned to Allardyce. “It’d be a good idea, sir, if you could be a bit more precise in telling us where you were last night. You said you went out of here about half past four, to Southwark, and didn’t get home until ten o’clock this morning. Make a list of everywhere you were and who saw you there.”

Allardyce said nothing.

“Mr. Allardyce,” Monk commanded his attention. “If you went out at half past four, you can’t have been expecting Mrs. Beck for a sitting.”

Allardyce frowned. “No . . .”

“Do you know why she came?”

He blinked. “No . . .”

“Did she often come without appointment?”

Allardyce pushed his hands through his black hair and looked at some distance only he could see. “Sometimes. She knew I liked to paint her. If you mean did anyone else know she was coming, I’ve no idea.”

“Did you plan to go out or was it on the spur of the moment?”

“I don’t plan, except for sittings.” Allardyce stood up. “I’ve no idea who killed her, or Sarah. If I did, I’d tell you. I don’t know anything at all. I’ve lost two of the most beautiful women I’ve ever painted, and two friends. Get out and leave me alone to grieve, you damn barbarians!”

There was little enough to be accomplished by remaining, and Monk followed Runcorn out into the streetin. Monk was startled how dark it was, more than just an autumn evening closed in. There was a gathering fog wreathing the gas lamps in yellow and blotting out everything beyond ten or fifteen yards’ distance. The fog smelled acrid, and within a few moments he found himself coughing.

“Well?” Runcorn asked, looking sideways at him, studying his face.

Monk knew what Runcorn was thinking. He wanted a solution, quickly if possible—in fact, he needed it—but he could not hide the edge of satisfaction that Monk could not produce it any more than he could himself.

“Thought so,” Runcorn said dryly. “You’d like to say it was Allardyce, but you can’t, can you?” He put his hands into his pockets, then, aware he

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher