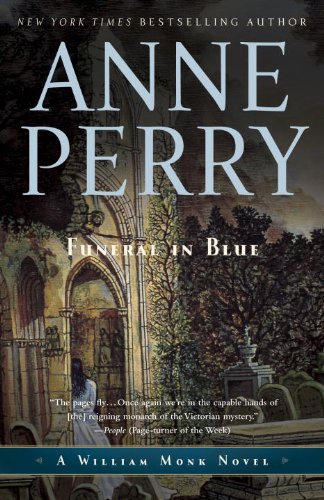

![William Monk 12 - Funeral in Blue]()

William Monk 12 - Funeral in Blue

herself shaking with release from the tension. Her head was pounding and her hands felt clammy, in spite of the cold.

She had not seen Kristian alone since the death of Elissa, except for moments in the hospital, standing in the corridor with the certain knowledge that someone else might pass at any moment. They had spoken of trivia. She had been thinking a hundred other things that she longed to be able to say, and the frustration of silence was almost unbearable. She was sorry for his pain and his loss. She wanted him to fight back with more passion, to defend himself, at least to speak openly, to share his grief rather than to close it away.

She had said none of it. She had allowed him all the time and the privacy he had wanted, simply watching and grieving for him. She had set aside her own hurt at being excluded, her confusion as to what he had felt for Elissa that he had deceived by silence as to what she was like.

Then she had begun to doubt herself. She had to remember more clearly the long hours they had spent together in the fever hospital in Limehouse, working all day and so often all night with the one passionate aim of saving lives, containing the infection. Had she deluded herself that their bond was personal, when it was only the shared understanding of suffering? Was it compassion for the sick which had warmed his eyes, and the knowledge that she felt it, devoted herself to it as he did, that had made him reach out to her?

He had never betrayed his marriage even by a word. Was that honor that had bound him, and for which she had so profoundly admired him? Or was there nothing in his silence that concerned her? Not unspoken loneliness at all?

She looked in the glass and saw herself as she had always been, a little short, definitely too broad, a face which her friends would have said was intelligent and full of character. Those indifferent to her would have described it with condescension as agreeable but plain. She had good skin, and good teeth even now, but she lacked prettiness, and the blemishes of age were all too apparent. How could she have been vain enough or silly enough to imagine any man married to Elissa would have felt anything but professional regard for her, a shared desire to heal some small portion of the world’s pain?

At least she had not ever spoken aloud. Although that was decency, not lack of emotion. But Kristian would never know that.

Today personal pride and emotions of any sort must be set aside. There was practical work to do, and the truth to be faced. She would go to the prison and visit Kristian, inform him of Fuller Pendreigh’s offer and Monk’s willingness to continue searching for some alternative theory to suggest to the jury. She already had a plan in mind, but for it to have even the faintest chance of success, she needed Kristian’s cooperation. She might have been useless at the arts of romance, but she was an excellent practical organizer, and she had never lacked courage.

By the time she reached the police station, she had decided to speak to Runcorn first, if he was in and would see her, although she intended to insist.

As it happened, no pressure was necessary, and she was conducted with some awe up the narrow stairs to a room rather obviously tidied up for her. Piles of papers with no connection to each other rested on the corner of the shelf, and pencils and quills had been gathered together and pushed into a cup to keep them from rolling. A clean sheet of blotting paper lay over the scratches and marks in the desk. On any other occasion she might have been gently amused.

Runcorn himself was standing up, almost to attention. “Good morning, Lady Callandra,” he said self-consciously. “What can I do for you? Please . . . please sit down.” He indicated the rather worn chair opposite his desk, and waited carefully until she was seated before he sat down himself. He looked uncomfortable, as if he wished to say something but had no idea how to begin.

“Good morning, Mr. Runcorn,” she replied. “Thank you for sparing me your time. I appreciate that you must be very busy, so I shall come to the point immediately. Mr. Monk told me that you were enquiring into Mr. Max Niemann’s visits to London, whether he was here at the time of Mrs. Beck’s death, and if he had come here on any other occasion recently. Is that correct?”

“Yes, it is, ma’am.” Runcorn was not quite certain how to address her, and it showed in his hesitation.

“And

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher