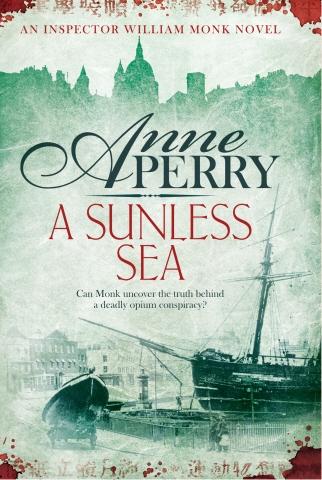

![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

stopped in mid-stride. “They had never had occasion to arrest her, or at least caution her regarding her activities as a prostitute?”

“That is what they said,” Monk agreed again.

“If she was indeed a prostitute, do you not find that remarkable?” Coniston asked with a lift of surprise in his voice.

Monk’s face was expressionless. “People often don’t recognize someone when they have died violently, especially if there is a lot of blood involved. People can look smaller than you remember them when they were alive. And if they are not dressed as you know them, or in a place where you expect to see them, you do not always realize who they are.”

Coniston looked as if that was not the answer he had wanted. He moved on. “Did you then make inquiries to find out who she was?”

“Of course.”

“Where did you inquire?” Coniston spread his hands, encompassing an infinity of possibilities.

“We spoke to local residents, shopkeepers, other women who lived in the area and with whom she might have been acquainted,” Monk answered, still hardly any emotion in his voice.

“When you say ‘women,’ do you mean prostitutes?” Coniston pressed.

Monk’s face was bland. Probably only Rathbone could see the tiny muscle ticking in his cheek.

“I mean laundresses, factory workers, peddlers, anyone who might have known her,” he said.

“Were you successful?” Coniston inquired courteously.

“Yes,” Monk told him. “She was identified as Zenia Gadney, a middle-agedwoman who lived quietly, by herself, at Fourteen Copenhagen Place, just beyond Limehouse Cut. She was known to several other people in the street.”

“How did she support herself?” Coniston was still calm and polite, but the tension in him was not missed by the jury. Watching them, Rathbone could feel it himself.

“She didn’t,” Monk answered. “There was a man who called on her once a month, and gave her sufficient funds for her needs, which appeared to be modest. We found no evidence of her having earned any money other than that, except for the very occasional small sewing job, which might have been as much for goodwill and companionship as for money.” Monk’s face was somber, his voice quiet, as if he too mourned not only her terrible death, but the seeming futility of her life.

Knowing him as he did, Rathbone had no difficulty reading the emotions in his face and his choice of words. He wondered if Coniston read it also. Would he judge him with any accuracy?

Coniston hesitated a moment, then went on. “I assume that, as a matter of course, you attempted to identify this man, and the kind of relationship he had with her?”

“Of course,” Monk answered. “He was Dr. Joel Lambourn, of Lower Park Street, Greenwich.”

“I see,” Coniston said quickly. “That would be the late husband of the accused, Mrs. Dinah Lambourn?”

Monk’s face was a blank slate. “Yes.”

“Did you go to see Mrs. Lambourn? Ask her about her husband’s connection with Mrs. Gadney?” Coniston said innocently. “It must have been unpleasant for you to have to inform her of her husband’s connection with the dead woman.” There was a touch of pity in his voice now.

“Yes, of course I did,” Monk answered him. His own expression was ironed clear of compassion as much as he could, and yet it still shone through.

The jury watched intently. Even Pendock in the judge’s seat leaned forward a little. There was a sigh of breath in the gallery, as if the tension had become too great.

“And her reaction?” Coniston prompted a little sharply, as if he was annoyed at having to ask.

“At first she said she did not know Mrs. Gadney,” Monk replied. “Then she admitted that she was aware that her husband had supported her until his death two months earlier.”

“She knew!” Coniston said loudly and clearly, even half turning toward the gallery so no one in the whole courtroom could have missed it. He swung back toward Monk. “Mrs. Lambourn knew that her husband had been visiting and paying Zenia Gadney for years?”

“She said so,” Monk agreed.

Rathbone made a small note on his paper in front of him.

“But first she denied it?” Coniston pressed. “Was she embarrassed? Angry? Humiliated? Afraid, even?”

Rathbone considered objecting on the grounds that such a judgment was not in Monk’s expertise, then changed his mind. It would be futile, merely drawing attention to his own desperation.

The shadow of a smile

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher