![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

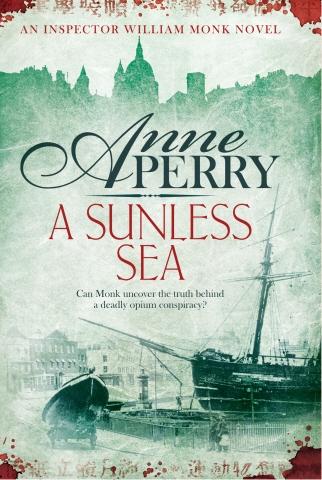

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

her own life, not someone else’s.

Wouldn’t she?

Was it conceivable that it was Dinah who had actually killed Joel Lambourn? Had either Monk or Rathbone even thought of that, and weighed it without the tangle of emotion her pain caused in them?

But Lambourn’s death had looked like suicide. It was even gentle, with the opium to dull the pain. There was no hatred there, not even any anger. But it robbed Dinah of the respectability, the social status, and most of the income to which she was accustomed. What about Adah and Marianne? Had she even thought of them? Did a womanever really forget her children? What had Lambourn left? Enough for them to live on, for Dinah to raise and successfully marry the two young girls?

Was it even physically possible that Dinah had done it alone? Had she lured him up to One Tree Hill in the middle of the night? Persuaded him to take the opium, then sit there while she cut his wrists, calmly picked up the bottle and the knife, and walked back home again to her children? Why take away the bottle and knife? That made no sense. If he had really committed suicide, they would have been there. And the fact that they were from her home wouldn’t need concealing, because it was his home, too!

If she were capable of such cold-blooded planning, why the insane rage in mutilating Zenia Gadney? And what could have provoked her, after years of knowing about the whole arrangement? Why suddenly commit two murders, two months apart?

It made no sense. There had to be another answer.

H ESTER SPENT THE REST of the day speaking to people in the area and learning a little more about Zenia Gadney, but nothing that altered the picture Gladys had given her of a quiet, rather sad woman. Apparently she had destroyed her youth with drink, but she also appeared to have beaten whatever demons had driven her then. For the last fifteen years she had lived in Copenhagen Place. She had done the odd job of sewing or mending for people, but more as a friend than for money. It was a way of associating with others, and having the occasional conversation. She appeared to be supported by Dr. Lambourn sufficiently that if she was careful, no other income had been necessary.

Several people said they saw her out walking quite often, in all weathers but the very worst. Most often it was along Narrow Street, beside the river. Sometimes she would stand with the wind in her face, looking south, watching the barges come and go. If you spoke to her she would answer, and she was always agreeable, but she seldom sought conversation herself.

No one spoke ill of her.

Hester went to stand in Narrow Street herself, the wind stingingher face, gray water glinting in the light. Hester had a strong sense of Zenia’s loneliness, perhaps of the regret that must have crowded her mind so many times. What had started her drinking in the first place? Some domestic tragedy? Perhaps the death of a child? A marriage that was desperately unhappy? Probably no one would ever know.

There seemed to be nothing in Zenia’s life that led to her terrible death, unless it was her association with Joel Lambourn. If it was not that, then she was no more than a chance victim, sacrificed to opportunity and insane rage.

Hester had begun with pity for Dinah, a woman robbed not only of the husband she loved, but, in a sense, of all that she had believed of the happiness in her life. The sweetness of her memories were now tainted forever. Soon she would lose her own life in the awful ritual punishment of hanging.

Now as Hester stood watching the gray water of the river swirl past her, her pity was for Zenia Gadney. The woman’s life had held so little comfort, and in the last decade and a half, almost no warmth of laughter, sharing, even touching another human being, apart from Joel Lambourn once a month, for money. Hester refused to try to picture that in her mind. What could he have wanted that was so strange or so obscene that his wife would not grant it to him, and he paid a sad prostitute in Limehouse instead?

She was glad that she did not need to know.

The water was loud on the shingle as the wash of a boat reached the shore on the low tide. A string of barges passed in midstream, laden with coal, timber, and bales stacked high. The men guiding them balanced with a rough, powerful grace, wielding their long poles. The wind was rising and smelled of salt and rain. Gulls screamed overhead, a long, mournful cry.

Hester felt she had exhausted the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher