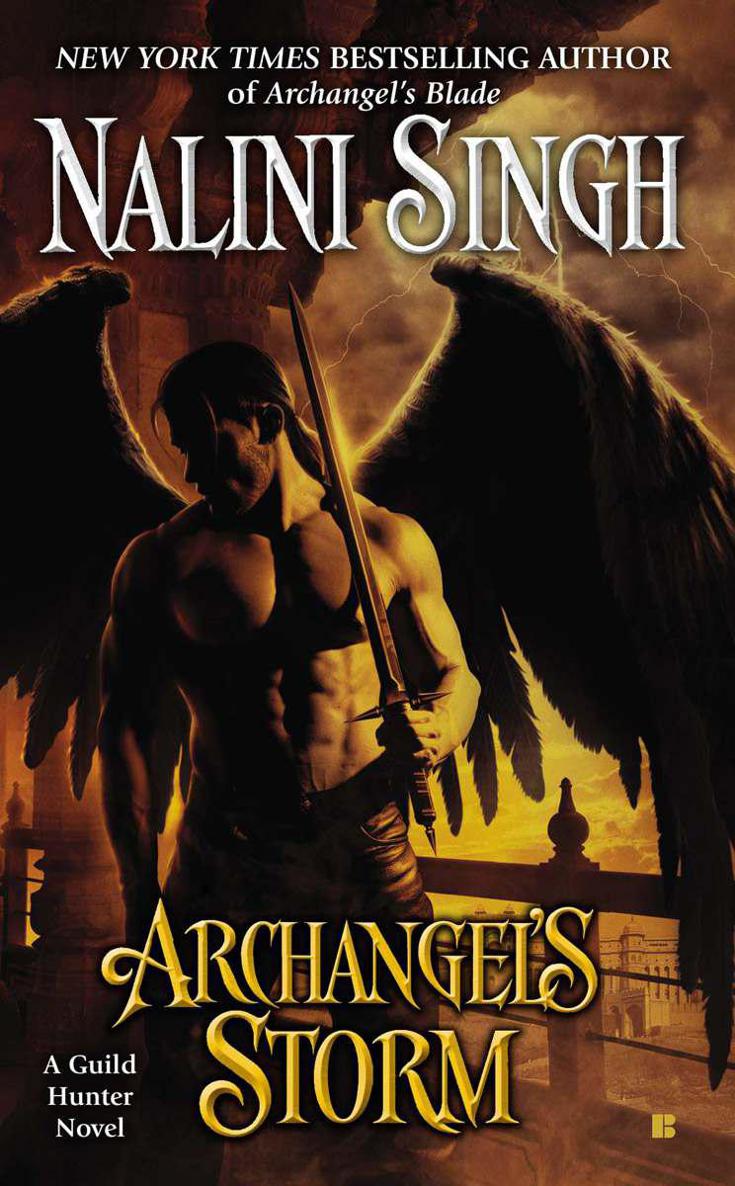

![Archangel's Storm]()

Archangel's Storm

he used the word, her shining black hair dancing in the sunshine.

The mat crackled under his feet, and he realized he’d moved, realized he was dragging the meat wearing the amethyst top to the other part that matched, that he was adding her arms and legs, the ripped and bloodied feathers of her silvery-white wings, his chest straining with the effort, the pieces too heavy for his small body. But he had to do it.

The sun hadn’t dried out the bits in the shade and hidden from direct light, and his hands became slippery with dark red once more. When her head slid out of his hands and thumped on the floor, he bit hard on his lip and picked it up again, stroking back the hair that had gotten in her eyes. “I’m sorry, Mama.” He had his mother’s hair, her skin, her eyes, she always said so. But today her eyes weren’t right, weren’t smiling as they always did when they turned his way.

Finally settling her head where it should be on her body, he knelt down on the mat that always made crisscross patterns on his knees and said, “Wake up now.”

His mother was an immortal, just like him. Only four hundred and sixty-five years old, but that was old enough.

Angels lived forever.

That’s what his mother said the mortals said, but she said angels simply lived a very long time.

He shook her shoulders, her brown skin cold instead of glowing with warmth. “Wake up.” He tried not to remember what else his mother had said, but her words whispered into his mind, spoken in the lyrical language of the island where she’d been born and lived until she was taken to school in a place she called the Refuge.

“Angels can die. It is a difficult thing but not impossible. Especially for younger angels.”

Now he looked at the chunk of meat wearing the amethyst silk, and he knew what that hole in her chest meant. Her heart was gone, ripped out. Her stomach, too, had a hole. And her head . . . it hadn’t been too heavy for him to lift. Because there was a hole in it, too.

All his mother’s insides were gone.

An angel of her age and power could not reawaken without her insides, could not reform. Still he shook her, telling her to “Wake up, wake up, wake up!” Until he realized he was screaming, when he was supposed to never, ever scream.

Shutting himself up by biting down on his lip again until it bled, he patted his mother’s hair back into place and rose, putting one bloody hand on the doorknob to open it. Silence greeted him on the other side. He followed the trail of dried blood, determined to find his mother’s insides. If he put them back, she would wake up, he knew she would.

His wings dragged on the ground, streaking dirt and rust red along the shiny wooden floors, and he knew his mother would scold him. He was always supposed to keep them up, so his flight muscles would grow strong, but he was so tired and hungry. “I’m sorry, Mama,” he whispered again. “I promise I’ll do better tomorrow.” After she was awake.

Outside, the full might of the sun was blinding, the light reflecting off the white sands on the other side of his mother’s lush garden, the water an endless blue horizon. He blinked until the spots faded, and continued on his task. The trail of sun-hardened black brown went around the side of the house and to what had been the small shed where his father had built things, like the instruments their friends took away to sell at the Refuge place and the toys Jason used to love.

Before.

Smoke still rose from the collapsed remnants of his father’s work house, but the fire had devoured a good meal and was settling down to sleep, the fallen beams glowing with a final few embers. He knew he wasn’t supposed to go near fire, but he went anyway, pushing away still-warm pieces with his hands. When the embers burned his skin, singed his feathers, he shook off the hurt and carried on, kicking aside the ash and the lumps of charcoaled wood until he saw his father’s head.

It was rolling around on the floor, all bone, the eye holes empty. His father’s body—charred black bones—lay in another part of the small building, and Jason knew then that his father had burned up his mother’s insides as well as his own, that he’d cut off his own head using the chopping thing he’d built . . . would have cut off Jason’s if Jason had made a sound when his father called out for him after the screams stopped and the blood began to seep through the trapdoor.

39

B ut maybe his father

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher