![Belladonna]()

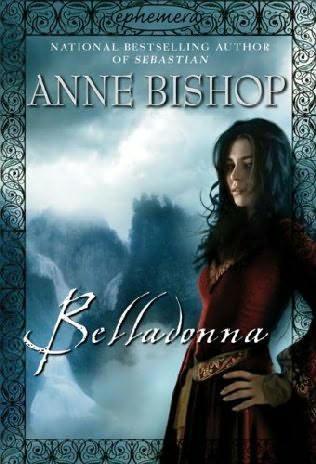

Belladonna

him, throwing clods of dirt that just missed hitting him and dirtying his new coat.

Until Rory had thrown a clod that hit him square in the back. Stung that the people in this village wouldn't let him have one nice thing, he turned and looked at Rory. "May you get everything you deserve."

"Ooooo," Rory said, waving his hands. "He's ill-wishing me. Ooooo."

They continued to follow him until they reached the old quarry. Then they abandoned him to play "dare you" — a game all the boys in the village had played at one time or another to prove manliness or bravery or some other foolish thing. Usually the game was played on the other side of the quarry, where there were slabs and ledges of stone that weren't too far below the top. A fall on that side of the quarry might end with a broken leg or arm. On this side was a steep slope that changed to a sheer drop to the quarry floor. Any boy who fell on this side of the quarry would end up at the bottom, broken and dying.

He'd sometimes wondered what would have happened if he'd kept going, kept walking. But the air around him had trembled with a discordant song, and something about those young voices pulled at him. So he'd turned and saw them standing much too close to the edge. But that was the whole point of playing "dare you." The quarry's edge wasn't stable. Walk too close and a section of stone might break away. The winner of the game was whichever boy stood closest to the edge and stamped a foot, daring the stone to break.

"They're not bad boys," he'd whispered as he'd watched the three shuffle up to the quarry's edge. "Well, two of them aren't.

Without Rory, the other two would settle down and grow up."

In that moment before things changed forever, he heard notes so harshly abrasive they made him wince. One harsh note, actually, and two others that weren't quite in tune. Two that might fit back into the song that was Raven's Hill if given a chance.

In that moment before things changed forever, he saw all three boys jump up and land on the edge with a two-footed stomp.

Before he could move, the boys disappeared, replaced by the roar of stone and air filled with dust.

Michael ran to the quarry, stopping a man-length from the new edge, then testing the ground, step by step, until he could look into the quarry.

Rory Calhoun hung on the edge of a new, sheer drop, impaled on a broken spire of stone. His eyes stared unblinking at the sky, but the fingers twitched, die hands tried to clench. Alive then ... for a few moments longer.

As he stared at the boy, Michael realized he was hearing terrified mewling. Realized Rory's legs hung over the drop.

"Boys?" he called.

"Help! Help!"

Two of them, alive. Clinging to their friend's legs. Which had probably contributed to that spire of stone punching through Rory's body.

As he stripped off his coat and dropped it, he studied the side of the quarry. There were now juts of stone he could stand on and knobs of stone for handholds. Best to belly over the side and lower himself down to the first ledge, which would get him close enough to reach the boys. He hoped.

The moment before he eased his legs over the edge, two things occurred to him: that the ledge might be a little too far down for him to get himself back out of the quarry, and that he couldn't let the boys see what had happened to Rory.

He grabbed his coat. With a wrist flick to spread the cloth, he dropped the coat over Rory. Then he lowered himself over the edge.

Stretched to his full length, his fingers clinging to the edge, his toes barely brushed the ledge beneath him. Would it hold him?

Would it hold him and the weight of a boy? It had to hold. Had to.

Saying a quick prayer to the Lady of Light, he let go of the edge, landing solidly on the stone beneath him. He pressed himself against the quarry wall, hardly daring to breathe while he waited a few moments to see if the ledge would hold. Then he pulled off his belt, made a loop at one end, and wrapped the leather around his fist a couple of times before he shifted his weight to bring himself closer to the other boys.

As clear as the memory was up to that point, the rest was fragmented images: a boy's terrified face looking up at him; the weight as a boy slipped a hand through the loop in the belt and let go of Rory's leg; the arrival of his friend Nathan, who had come looking for him; the look in the eyes of the men who had helped pull the boys out of the quarry — a look that said they weren't sure if

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher