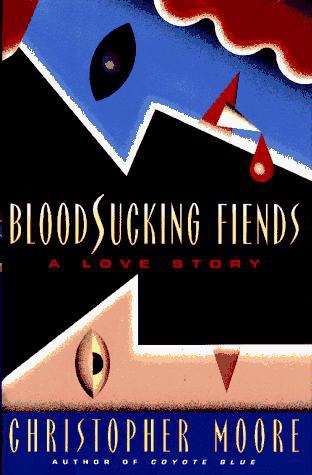

![Bloodsucking fiends: a love story]()

Bloodsucking fiends: a love story

when no one can play the notes or understand the lyrics? I'm alone.

Cavuto came through the double doors of the emergency room and joined Rivera, who was standing by the brown, City-issue Ford smoking a cigarette.

"What was the call?" Cavuto asked.

"We got another one. Broken neck. South of Market. Elderly male."

"Fuck," Cavuto said, yanking open the car door. "What about blood loss?"

"They don't know yet. This one's still warm." Rivera flipped his cigarette butt into the parking lot and climbed into the car. "You get anything more out of LaOtis?"

"Nothing important. They weren't doing their laundry, they went in looking for the girl, but he's sticking with the ninja story."

River started the car and looked at Cavuto. "You didn't rough him up?"

Cavuto pulled a Cross pen out of his shirt pocket and held it up. "Mightier than the sword."

Rivera cringed at the thought of what Cavuto might have done to LaOtis with the pen. "You didn't leave any marks, did you?"

"Lots," Cavuto grinned.

"Nick, you can't do that kind of -"

"Relax," Cavuto interrupted. "I just wrote, 'Thanks for all the information; I'm sure we'll get some convictions out of this,' on his cast. Then I signed it and told him that I wouldn't scratch it out until he told me the truth."

"Did you scratch it out?"

"Nope."

"If his friends see it, they'll kill him."

"Fuck him," Cavuto said. "Ninja redheads, my ass."

Four in the morning. Jody watched neon beer signs buzzing color across the dew-damp sidewalks of Polk Street. The street was deserted, so she played sensory games to amuse herself – closing her eyes and listening to the soft scratch of her sneakers echoing off the buildings as she walked. If she concentrated, she could walk several blocks without looking, listening for the streetlight switches at the corners and feeling the subtle changes in wind currents at the cross streets. When she felt she was going to run into something, she could shuffle her feet and the sound would form a rough image in her mind of the walls and poles and wires around her. If she stood quietly, she could reach out and form a map of the whole City in her head – sounds drew the lines, and smells filled in the colors.

She was listening to the fishing boats idling at the wharf a mile away when she heard footsteps and opened her eyes. A single figure had rounded the corner a couple of blocks ahead of her and was walking, head down, up Polk. She stepped into the doorway of a closed Russian restaurant and watched him. Sadness came off him in black waves.

His name was Philip. His friends called him Philly. He was twenty-three. He had grown up in Georgia and had run away to the City when he was sixteen so he wouldn't have to pretend to be something he was not. He had run away to the City to find love. After the one-night stands with rich older men, after the bars and the bathhouses, after finding out that he wasn't a freak, that there were other people just like him, after the last of the confusion and shame had settled like red Georgia dust, he'd found love.

He'd lived with his lover in a studio in the Castro district. And in that studio, sitting on the edge of a rented hospital bed, he had filled a syringe with morphine and injected it into his lover and held his hand while he died. Later, he cleared away the bed pans and the IV stand and the machine that he used to suck the fluid out of his lover's lungs and he threw them in the trash. The doctor said to hold on to them – that he would need them.

They buried Philly's lover in the morning and they took the embroidered square of fabric that was draped on the casket and folded it and handed it to him like the flag to a war widow. He got to keep it for a while before it was added to the quilt. He had it in his pocket now.

His hair was gone from the chemotherapy. His lungs hurt, and his feet hurt; the sarcomas that spotted his body were worst on his feet and his face. His joints ached and he couldn't keep his food down, but he could still walk. So he walked.

He walked up Polk Street, head down, at four in the morning, because he could. He could still walk.

When he reached the doorway of a Russian restaurant, Jody stepped out in front of him and he stopped and looked at her.

Somewhere, way down deep, he found that there was a smile left. "Are you the Angel of Death?" he asked.

"Yes," she said.

"It's good to see you," Philly said.

She held her arms out to him.

Chapter 21 – Angel Dust

The bed of Simon's

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher