![Brave New Worlds]()

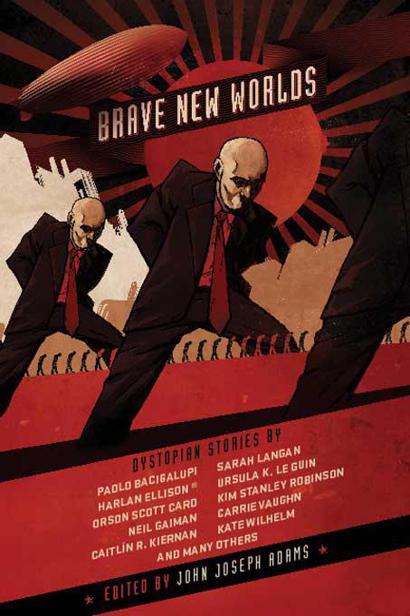

Brave New Worlds

involving military interests will be noted and filed with the Greater Office of Homeland Security, the FBI, CIA, and Interpol.

She frowns and shuts off the portable, setting it down on the small bamboo table beside the bed. Tomorrow, she'll file an appeal on the search, citing the strange piece of mail as just cause. Her record is good and there's nothing to worry about. Outside, the rain is coming down harder than ever, falling like it means to wash Manhattan clean or drown it trying, and she sits listening to the storm, wishing that she could have gone into work.

Monday again, after the morning's meeting, and Farasha is sitting at her desk. Someone whispers "Woolgathering?", and she turns her head to see who's spoken. But it's only Nadine Palmer, who occupies the first desk to her right. Nadine Palmer, who seems intent on ignoring company policy regarding unnecessary speech and who's likely to find herself unemployed if she keeps it up. Farasha knows better than to tempt the monitors by replying to the question. Instead, she glances down at the pad in front of her, the sloppy black lines her stylus has traced on the silver-blue screen, the two Hindi words—"Sonepur" and "Mahanadi"—the city and the river, two words that have nothing whatsoever to do with the Nakamura-Ito account. She's scribbled them over and over, one after the other. Farasha wonders how long she's been sitting there daydreaming, and if anyone besides Nadine has noticed. She looks at the clock and sees that there's only ten minutes left before lunch, then clears the pad.

She stays at her desk through the lunch hour, to make up the twelve minutes she squandered "woolgathering. " She isn't hungry, anyway.

At precisely two p. m. , all the others come back from their midday meals, and Farasha notices that Nadine Palmer has a small stain that looks like ketchup on the front of her pink blouse.

At three twenty-four, Farasha completes her second post-analysis report of the day.

At four thirteen, she begins to wish that she hadn't found it necessary to skip lunch.

And at four fifty-six, she receives a voicecall informing her that she's to appear in Mr. Binder's office on the tenth floor no later than a quarter past five. Failure to comply will, of course, result in immediate dismissal and forfeiture of all unemployment benefits and references. Farasha thanks the very polite, yet very adamant young man who made the call, then straightens her desk and shuts off her terminal before walking to the elevator. Her mouth has gone dry, and her heart is beating too fast. By the time the elevator doors slide open, opening for her like the jaws of an oil-paint shark, there's a knot deep in her belly, and she can feel the sweat beginning to bead on her forehead and upper lip. Mr. Binder's office has a rhododendron in a terra-cotta pot and a view of the river and the city beyond. "You are Ms. Kim?" he asks, not looking up from his desk. He's wearing a navy-blue suit with a teal necktie, and what's left of his hair is the color of milk.

"Yes sir. "

"You've been with the company for a long time now, haven't you? It says here that you've been with us since college. "

"Yes sir, I have. "

"But you deleted an unread interdepartmental memorandum yesterday, didn't you?"

"That was an accident. I'd intended to read it. "

"But you didn't . "

"No sir," she replies and glances at the rhododendron.

"May I ask what is your interest in India, Ms. Kim?" and at first she has no idea what he's talking about. Then she remembers the letter—invitation transcend—and her web search on the two words she'd caught herself doodling earlier in the day.

"None, sir. I can explain. "

"I understand that there was an incident report filed yesterday evening with the GOHS, a report filed against you, Ms. Kim. Are you aware of that?"

"Yes sir. I'd meant to file an appeal this morning. It slipped my mind—"

"And what are your interests in India?" he asks her again and looks up, finally, and smiles an impatient smile at her.

"I have no interest in India, sir. I was just curious, that's all, because of a letter—"

"A letter?"

"Well, not really a letter. Not exactly. Just a piece of spam that got through—"

"Why would you read unsolicited mail?" he asks.

"I don't know. I can't say. It was the second time I'd received it, and—"

"Kim. Is that Chinese?"

"No, sir. It's Korean. "

"Yes, of course it is. I trust you understand our position in this very delicate matter, Ms. Kim.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher