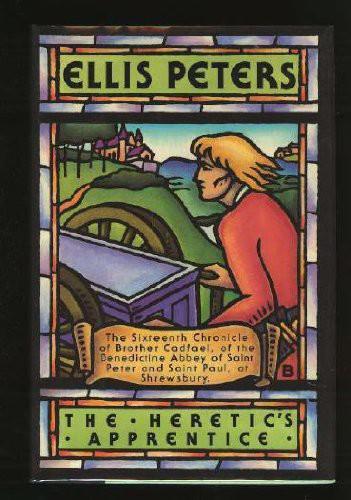

![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

into his ear. They must have sat there for above half an hour, and then the other one went off and left him to himself another half hour, brooding, it seemed. He was never a drinker, though, Aldwin. Sober as stone when he got up and went out at the door, and without a word, mind you. Too late for words now, poor soul."

"Who was it with him?" demanded the questioner eagerly. "What's his name?"

"I don't know that I ever heard his name, but I know who he is. He works for the same master - that shepherd of theirs who keeps the flock they have out on the Welsh side of town."

"Conan?" echoed Jevan, turning from the shelves of his shop with a creamy skin of vellum in his hands. "He's off with the sheep, and he may very well sleep up there; these summer nights he often does. Why, is there anything new? He told you what he knew, what we all knew, this morning. Should we have kept him here? I knew of no reason you might need him again."

"Neither did I then," agreed Hugh grimly. "But it seems Master Conan told no more than half a tale, the half you and all the household could bear witness to. Not a word about running after Aldwin and haling him away into the tavern in the Three-Tree Shut, and keeping him there more than half an hour."

Jevan's level dark brows had soared to his hair, and his jaw dropped for a moment. "He did that? He said he'd be off to the flock and get on with his work for the rest of the day. I took it that's what he'd done." He came slowly to the solid table where he folded his skins, and spread the one he was carrying carefully over it, smoothing it out abstractedly with a sweep of one long hand. He was a very meticulous man. Everything in his shop was in immaculate order, the uncut skins draped over racks, the trimmed leaves ranged on shelves in their varied sizes, and the knives with which he cut and trimmed them laid out in neat alignment in their tray, ready to his hand. The shop was small, and open on to the street in this fine weather, its shutters laid by until nightfall.

"He went into the alehouse with Aldwin in his arm, so the potman says, about three o'clock. They were there a good half hour, with Conan talking fast and confidentially into Aldwin's ear. Then Conan left him there, and I daresay did go to his work, and Aldwin still sat there another half hour alone. That's the story my man unearthed, and that's the story I want out of Conan's hide, along with whatever more there may be to tell."

Jevan stroked his long, well-shaven jaw and considered, with a speculative eye upon Hugh's face. "Now that you tell me this, my lord, I must say I see more in what was said yesterday than I saw at the time. For when Aldwin said he must go and try to overtake that boy he'd done his best to ruin, and go with him to the monks to withdraw everything he'd said against him, Conan did tell him not to be a fool, that he'd only get himself into trouble, and do no good for the other lad. He tried his best to dissuade him. But I thought nothing of it but that it was good sense enough, and all he meant was to haul Aldwin back out of danger. When I said let him go, if he's bent on it, Conan shrugged it off, and went off about his own business. Or so I thought. Now I wonder. Does not this sound to you as though he spent another half hour trying to persuade the poor fool to give up his penitent notion? You say it was he was doing the talking, and Aldwin the listening. And another half hour still before Aldwin could make up his mind to jump one way or the other."

"It sounds like that indeed," said Hugh. "Moreover, if Conan went off content, and left him to himself, surely he thought he had convinced him. If it meant so much to him he would not have let go until he was satisfied he'd got his way. But what I do not understand is why it should matter so gravely to him. Is Conan the man to venture so much for a friend, or care so much into what mire another man blundered?"

"I confess," said Jevan, "I've never thought so. He has a very sharp eye on his own advantage, though he's a good worker in his own line, and gives value for what he's paid."

"Then why? What other reason could he have for going to such pains to persuade the poor wretch to let things lie? What could he possibly have against Elave, that he should want him dead, or buried alive in a church prison? The lad's barely home. If they've exchanged a dozen words that must be the measure of it. If it's not concern for Aldwin or a grudge against Elave this

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher