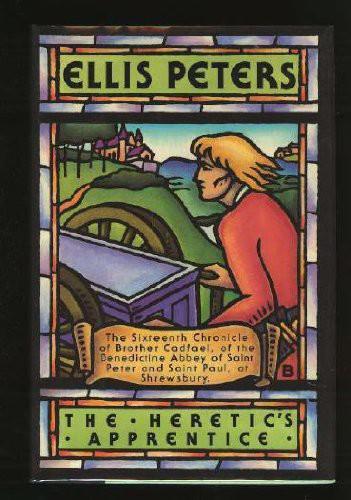

![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

Lythwood's house, that's certain. It was more than an hour later, maybe as much as an hour and a half."

"He's sure of that?" demanded Hugh. "There's no real check there, not in quiet times. He could be hazy about time passing."

"He's sure. He saw them all come back after the hubbub they had here at chapter, Aldwin and the shepherd first and the girl after, and it seemed to him they were all of them in an upset. He'd heard nothing then of what had happened, but he did notice the fuss they were in, and long before Aldwin came down to the gate again the whole tale was out. The porter was all agog when he laid eyes on the very man coming down the Wyle. He was hoping to stop him and gossip, but Aldwin went past without a word. Oh, he's sure enough! He knows how long had passed."

"So all that time he was still in the town," said Hugh, and gnawed a thoughtful lip. "Yet in the end he did cross the bridge, going where he'd said he was going. But why the delay? What can have kept him?"

"Or who?" suggested Cadfael.

"Or who! Do you think someone ran after him to dissuade him? None of his own people, or they would have said so. Who else would try to turn him back? No one else knew what he was about. Well," said Hugh, "nothing else for it, we'll walk every yard of the way from Lythwood's house to the bridge, and hammer on every door, until we find out how far he got before turning aside. Someone must have seen him, somewhere along the way."

"I fancy," said Cadfael, pondering all he had seen and known of Aldwin, which was meagre enough and sad enough, "he was not a man who had many friends, nor one of any great resolution of mind. He must have had to pluck up all his courage to accuse Elave in the first place. It would cost him more to withdraw his accusation, and put himself in the way of being suspect of perjury or malice or both. He may well have taken fright on the way, and changed his mind yet again, and decided to let well or ill alone. Where would a solitary dim soul like that go to think things out? And try to get his courage back? They sell courage of a sort in the taverns. And another sort, though not for sale, a man can find in the confessional. Try the alehouses and the churches, Hugh. In either a man can be quiet and think."

It was one of the young men-at-arms of the castle garrison, not at all displeased at being given the task of enquiring at the alehouses of the town, who came up with the next link in Aldwin's uncertain traverse of Shrewsbury. There was a small tavern in a narrow, secluded close off the upper end of the steep, descending Wyle. It was sited about midway between the house near Saint Alkmund's church and the town gate, and the lanes leading to it were shut between high walls, and on a feast day might well be largely deserted. A man overtaken by someone bent on changing his mind for him, or suddenly possessed by misgivings calculated to change it for him without other persuasion, might well swerve from the direct way and debate the issue over a pot of ale in this quiet and secluded place. In any case, the young enquirer had no intention of missing any of the places of refreshment that lay within his commission.

"Aldwin?" said the potman, willing enough to talk about so sensational a tragedy. "I only heard the word an hour past. Of course I knew him. A silent sort, mostly. If he did come in he'd sit in a corner and say hardly a word. He always expected the worst, you might say, but who'd have thought anyone would want to do him harm? He never did anyone else any that I knew of, not till this to-do yesterday. The talk is that the lad he informed on has got his own back with a vengeance. And him with trouble enough," said the potman, lowering his voice confidentially. "If the Church has got its claws into him, small need to go crying out for worse."

"Did you see the man yesterday at all?" asked the man-at-arms.

"Aldwin? Yes, he was here for a while, up in the corner of the bench there, as glum as ever. I hadn't heard anything then about this business at the abbey, or I'd have taken more notice. We'd none of us any notion the poor soul would be dead by this morning. It falls on a man without giving him time to put his affairs in order."

"He was here?" echoed the enquirer, elated. "What time was that?"

"Well past noon. Nearly three, I suppose, when they came in."

"They? He wasn't alone?"

"No, the other fellow brought him in, very confidential, with an arm round his shoulders and talking fast

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher