![Burning the Page: The eBook revolution and the future of reading]()

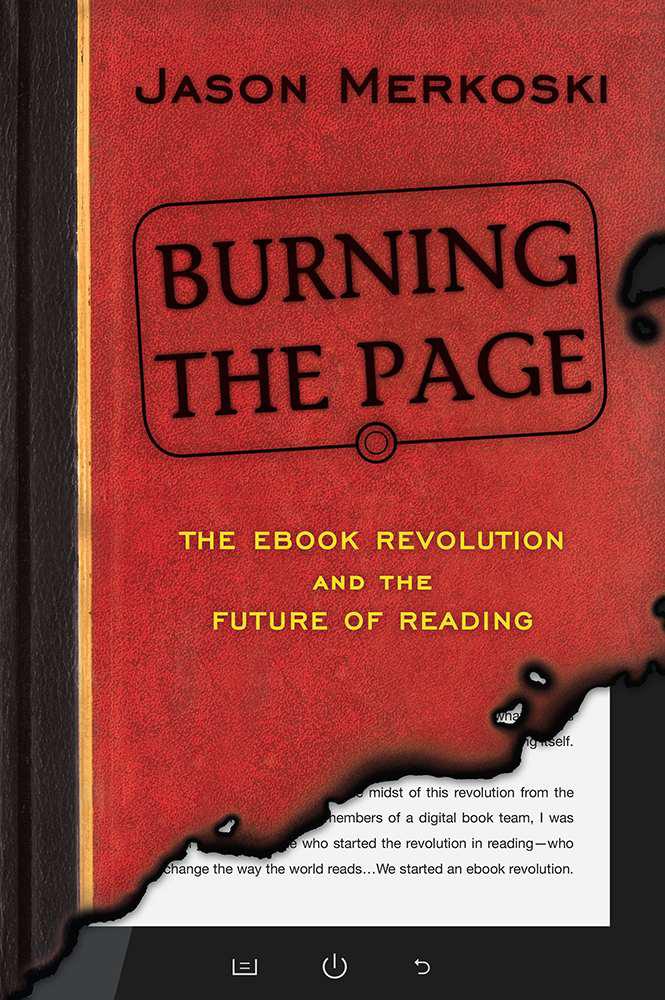

Burning the Page: The eBook revolution and the future of reading

from millions on a whim and begin reading it in a minute. The pace of technological change—though thrilling—is often confusing. And you can feel like you’re never quite caught up. You can subscribe to a hundred news feeds, if you know how to do that, and you still won’t be caught up, because the pace of technological change outpaces even specialists in the field.

It’s no wonder that a lot of the people I talk to are confused by ebooks. They don’t know which way to turn, which page to turn, which e-reader to use, or why they should even use them. And I totally empathize about how confusing technology can be. But technology is just a tool, like hammers and nails, although fussier, more prone to crashing, and more in need of firmware updates and special USB cables.

Once you get your head behind the ebook revolution, once you untangle yourself from all the different power cords and USB cords and actually start reading an ebook, I think you’ll realize as I did how useful these books are for culture, for reading. Ebooks, more than print books, offer an immediacy of meaning. After all, a dictionary is built into most e-readers, so the definition of an unfamiliar word is usually just one click away.

If this alone isn’t an educational improvement, then consider communal annotations and how they help readers to understand a digital textbook better. Each reader can make their own annotations to the same digital book, and all annotations across multiple readers can be added together. Some e-readers, like Amazon’s, show you the number of times that a given passage has been annotated. There’s often a wisdom to crowds, and in many cases, the most frequently annotated lines in a book are the most salient, the most useful for learning that chapter’s point.

» » »

This, though, is the paradox of ebooks: if you accept that children should read and that ebooks can teach as much as a print book, why didn’t we digitize textbooks first? Because we didn’t. Instead, we digitized fiction, sci-fi, romances, The New York Times bestsellers, and yes, pornography. Stuff we knew we could sell. But it’s content that hasn’t reached children in a significant way.

This is the central paradox of our ebook revolution: digital content won’t really succeed until it’s part of our culture from a very early age, and I mean from first grade onward, from the time children start reading. E-readers need to be flexible and sophisticated enough in their features to allow that. Right now, they’re just not adequate.

There are some neat experiments—as I write this, for example, I have friends in the publishing industry who have quit their jobs in Manhattan and gone to work in Silicon Valley for a company that builds e-readers for students. These devices have two folding screens, side by side like pages in a book, that allow you to write and scribble and draw and download and read books.

Tech experiments like this are what we need to really make education work digitally. And until we do that, ebooks will be something that’s bolted on to our culture. Ebooks won’t really be part of our culture until we’re raised with them, until we’re digital natives who stare with newborn eyes at these phosphorescent eInk displays.

Of course, a part of me yearns for good old-fashioned print books. And if I ever had a child, I can see how difficult it would be for me to choose whether to let the child read ebooks or use a computer or even have a smartphone. I’m sensitive to these issues, and a lot of parents I talk to also are worried that their kids will be distracted from reading by videos or social networking apps on an iPad or screeching monkeys in a game built into an ebook.

Teachers are worried too.

Professors are bemoaning the loss of critical thinking skills in today’s students and the loss of active reading skills. When we passively consume content, lazily let our brains stop doing the hard work of reading, and turn instead to the distractions of tweets and games, we’re changing our brains. We are what we eat, and the same is true of our digital diet. We are the media we consume, distractions and all. In the Stone Age, our ancestors listened to birdsong and bee hum, and that was media enough for their minds. Then we developed song and story. But now we’re no longer content with the oral tradition, as Socrates was, nor are we content with reading and writing. We want distractions. And we want digital distractions

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher