![Cyberpunk]()

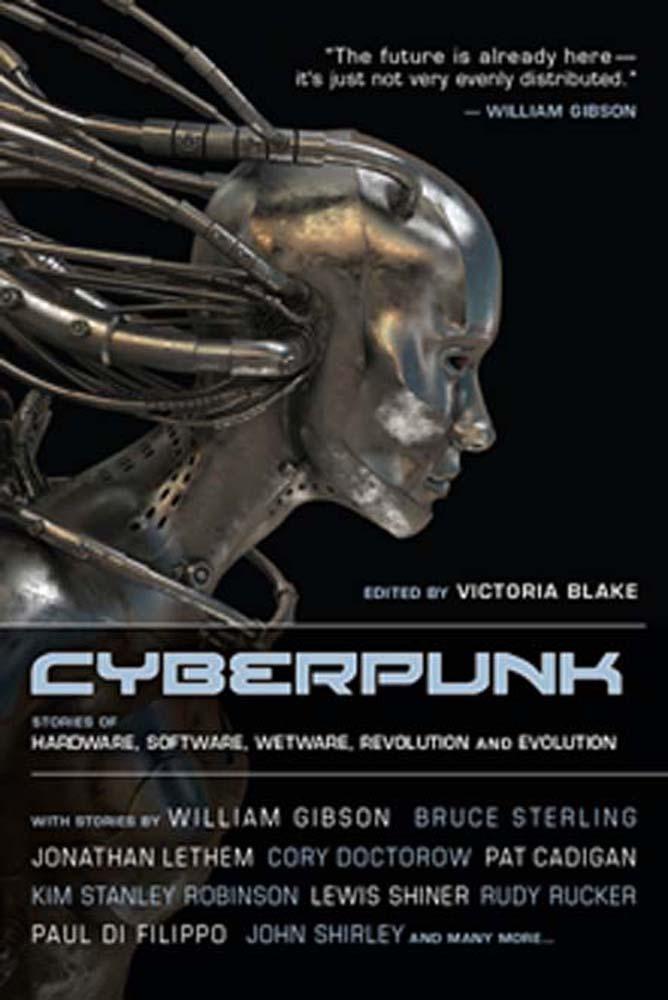

Cyberpunk

diagrams.

“. . . right after death,” Karla was saying in her low, hypnotic voice. “Jack’s complete software is in here as well as his genetic code. There’s only been a few of these made . . . it’s more than just science, it’s magic.” She clicked the tape into the player. “Go on, Alvin, turn Jack on. He’ll enjoy meeting you.”

I felt dizzy and confused. How long had I been sitting here? How long had she been talking? I reached for the switch, then hesitated. This scene had gotten so unreal so fast. Maybe she’d drugged the coffee?

“Don’t be afraid. Turn him on.” Karla’s voice seemed to come from a long way away. I clicked the switch.

The tape whined on its spools. I could smell something burning. A little puff of smoke floated up from the tape-player’s cone, and then there was more smoke, lots of it. The thick plume writhed and folded back on itself, forming layer after layer of intricate haze.

The ghostly figure thickened and drew substance from the player’s cone. At some point it was finished. Jack Kerouac was there standing over me with a puzzled frown.

Somehow Karla’s coven had caught the Kerouac of 1958, a tough, greasy-faced mind-assassin still years away from his eventual bloat and blood-stomach death.

“I was afraid he’d look like a corpse,” I murmured to Karla.

“Well, I feel like a corpse—say a dead horse—what happened?” said Kerouac. He walked over to the window and looked out. “Whooeee, this ain’t even Cleveland or the golden tongues of flame. Got any hoocha?” He turned and glared at me with eyes that were dark vortices. Everything about him was right except the eyes.

“Do you have any brandy?” I asked Karla.

“No, but I could begin undressing.”

Kerouac and I exchanged a glance of mutual understanding. “Look,” I suggested, “Jack and I will go out for a bottle and be right back.”

“Oh all right,” Karla sighed. “But you have to carry the player with you. And hang onto it !”

The soul-player had a carrying strap. As I slung it over my shoulder, Kerouac staggered a bit. “Easy, Jackson,” he cautioned.

“My name’s Alvin, actually,” I said.

“Al von Actually,” muttered Kerouac. “Let’s rip this joint.”

We clattered down the stairs, his feet as loud as mine. Jack seemed a little surprised at the street-scene. I think it was his first time in Germany. I wasn’t too well-dressed, and with Jack’s rumpled hair and filthy plaid shirt, we made a really scurvy pair of Americans. The passers-by, handsome and nicely dressed, gave us wide berth.

“We can get some brandy down here,” I said, jerking my head. “At the candy store. Then let’s go sit by the river.”

“Twilight of the gods at River Lethe. In the groove, Al, in the gr-gr-oove.” He seemed fairly uninterested in talking to me and spoke only in such distracted snatches, spoke like a man playing pinball and talking to a friend over his shoulder. Off and on I had the feeling that if the soul-player were turned off, I’d be the one to disappear. But he was the one with black whirlpools instead of eyes. Kerouac was the ghost, not me.

But not quite ghost either; his grip on the bottle was solid, his drinking was real, and so was mine, of course, as we passed the liter back and forth, sitting on the grassy meadow that slopes down the Neckar River. It was March 12th, basically cold, but with a good strong sun. I was comfortable in my old leather jacket and Jack, Jack was right there with me.

“I like this brandy,” I said, feeling it.

“Bee-a-zooze. What do you want from me anyway, Al? Poke a stick in a corpse, get maggots come up on you. Taking a chance, Al, for whyever?”

“Well, I . . . you’re my favorite writer. I always wanted to be you. Hitchhike stoned and buy whores in Mexico. I missed all that, I mean I did it, but differently. I guess I want the next kids to like me like I like you.”

“Lot of like, it’s all nothing. Pain and death, more death and pain. It took me twenty years to kill myself. You?”

“I’m just starting. I figure if I trade some of the drinking off for weed, I can stretch it out longer. If I don’t shoot myself. I can’t believe you’re really here. Jack Kerouac.”

He drained the rest of the bottle and pitched it out into the river. A cloud was in front of the sun now and the water was grey. It was, all at once, hard to think of any good reason for living. At least I had a son.

“Look in my eyes,”

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher