![Cyberpunk]()

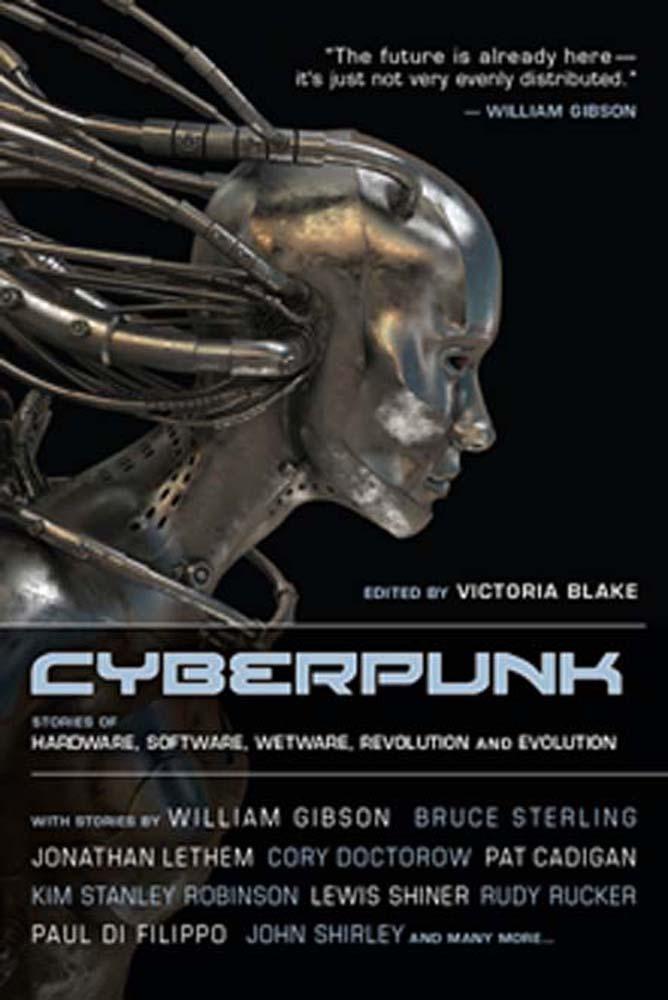

Cyberpunk

and went home.

After the potatoes were boiled and mashed and Debra was fed, he went to the bathroom and showered until someone hammered on the door. Back in his room he still felt hot, and he had trouble catching his breath. Debra rolled from side to side, moaning. Sometimes he was sure she was getting sicker, and at the thought his fear spiked up and through him again; he got so scared he couldn’t breathe at all . . . “I’m hungry, Lee. Can’t I have nothing more to eat?”

“Tomorrow, Deb, tomorrow. We ain’t got nothing now.”

She fell into an uneasy sleep. Lee sat on his mattress and stared out the window. White-orange clouds sat overhead, unmoving. He felt a bit dizzy, even feverish, as if he was coming down with whatever Debra had. He remembered how poor he had felt even back when he had had his crops to sell, when each month ended with such a desperate push to make rent. But now . . . He sat and watched the shadowy figure of Debra, the walls, the hot plate and utensils in the corner, the clouds out the window. Nothing changed. It was only an hour or two before dawn when he fell asleep, still sitting against the wall.

Next day he battled fever to seek out potato money from the pay phones and the gutters, but he only had thirty-five cents when he had to quit. He drank as much water as he could hold, slept in the park, and then went to see Victor.

“Vic, let me borrow your harmonica tonight.”

Victor’s face squinted with distress. “I can’t, Robbie. I need it myself. You know—” pleading with him to understand.

“I know,” Lee said, staring off into space. He tried to think. The two friends looked at each other.

“Hey, man, you can use my kazoo.”

“What?”

“Yeah, man, I got a good kazoo here, I mean a big metal one with a good buzz to it. It sounds kind of like a harmonica, and it’s easier to play it. You just hum notes.” Lee tried it. “No, hum, man. Hum in it.”

Lee tried again, and the kazoo buzzed a long crazy note.

“See? Hum a tune, now.”

Lee hummed around for a bit.

“And then you can practice on my harmonica till you get good on it, and get your own. You ain’t going to make anything with a harmonica till you can play it, anyway.”

“But this—” Lee said, looking at the kazoo.

Victor shrugged. “Worth a try.”

Lee nodded. “Yeah.” He clapped Victor on the shoulder, squeezed it. Pointed at Victor’s sign, which said, He’s a musician! “You think that helps?”

Victor shrugged. “Yeah.”

“Okay. I’m going to get far enough away so’s I don’t cut into your business.”

“You do that. Come back and tell me how you do.”

“I will.”

So Lee walked south to Connecticut and M, where the sidewalks were wide and there were lots of banks and restaurants. It was just after sunset, the heat as oppressive as at midday. He had a piece of cardboard taken from a trash can, and now he tore it straight, took his ballpoint from his pocket, and copied Delmont’s message. PLEASE HELP—HUNGRY. He had always admired its economy, how it cut right to the main point.

But when he got to what appeared to be a good corner, he couldn’t make himself sit down. He stood there, started to leave, returned. He pounded his fist against his thigh, stared about wildly, walked to the curb, and sat on it to think things over.

Finally he stepped to a bank pillar mid-sidewalk and leaned back against it. He put the sign against the pillar face out, and put his old baseball cap upside-down on the ground in front of him. Put his thirty-five cents in it as seed money. He took the kazoo from his pocket, fingered it. “Goddamn it,” he said at the sidewalk between clenched teeth. “If you’re going to make me live this way, you’re going to have to pay for it.” And he started to play.

He blew so hard that the kazoo squealed, and his face puffed up till it hurt. “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean,” blasted into all the passing faces, louder and louder.

When he had blown his fury out he stopped to consider it. He wasn’t going to make any money that way. The loose-ties and the career women in dresses and running shoes were staring at him and moving out toward the curb as they passed, huddling closer together in their little flocks as their bodyguards got between him and them. No money in that.

He took a deep breath, started again. “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” It really was like singing. And what a song. How you could put your heart into that one,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher