![Devils & Blue Dresses: My Wild Ride as a Rock and Roll Legend]()

Devils & Blue Dresses: My Wild Ride as a Rock and Roll Legend

taking place. I rammed it over and over again, each time imagining what I was going to do to the two assholes who had picked up the road bitch and left the star’s girlfriend in the back of the truck to freeze. I hit the wall so many times that I tore through the sheet metal. Finally the truck stopped and they came around back to open the trailer. The road dog disappeared and Kimberly was allowed to finish the trip in the cab with the heater. I stayed in back, smoked a joint, and was relieved that I had been able to give my precious love the respect she deserved. I couldn’t give her money.

When we loaded our equipment truck for long trips, there were large stacks of

Creem

magazines to be dropped off at various locations along our route. Barry had not yet made his distribution deal with Curtis Distributors in New York, so this was the way he shipped some of the magazine without having to pay mailing or freight charges. We stayed at cheap little motels that never had telephones or candy machines that worked. Charlie Auringer sometimes accompanied us as road manager and magazine distributor. It was a seemingly endless journey that saw quite a few personnel changes in the band and had an air about it that suggested the same kind of tedium and fruitless movement I had experienced with the Wheels on our initial stay in New York. We didn’t know if or when we were going to record, and there was very little money. We lived almost as beggars, but at least we were able to keep a roof over our heads when we arrived back home. Then, at last, Barry was ready with his plan.

My hair had grown below my shoulders and I had grown a mustache to augment my bell-bottom jeans, worn out shoes, and raggedy t-shirts. I looked like a bum. Actually, I couldn’t afford any better. Kimberly had an equally depressing wardrobe but, because of her magnificent body, no one seemed to notice. She also kept what we called “straight clothes” that she used for her work as a Kelly Girl temp worker. We struggled for money but it never became an issue. In fact, it fit right in with the counter-culture view of materialism and the anti-establishment mood of the times. Still, it hurt the daythe repo man came to take away my car. I didn’t want to be embarrassed, so I went down to meet him and give him the keys. He laughed as he pulled away.

Clearly, these were not the gravy years of my tenure with Bob Crewe, and I spent more than one night trying to reconcile thirteen records on the charts, three top tens, two top twenties and several top forties––millions upon millions sold for what? A fifteen thousand dollar advance for the house Susan and I had briefly owned. Meanwhile, the

Detroit Free Press

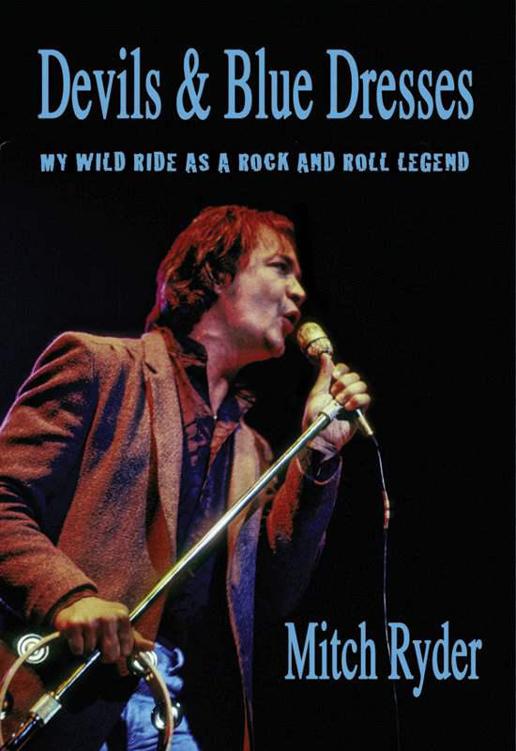

wanted to do a cover story on me for their weekly entertainment insert. The rough-looking cover picture pretty much said it all.

In a rare lucid moment, I willed myself to believe I was young enough to overcome this situation and establish myself back onto some sound financial footing. So, I turned my attention to the band, which was now known as Detroit. My self-esteem and confidence had been so shaken by the years in New York, and our current situation so devoid of monetary security, that I no longer felt like the “singular star” of the past and so I chose, in my weakened state, to simply become a member of a group. I was running from Mitch Ryder. My idea was to contribute equally to a project and share equally in its returns.

Paramount saw things differently and changed the name from Detroit, to Detroit featuring Mitch Ryder. There ended up being four different singers who did solos on the album, and that made me happy. The recording itself was put together piece-meal, because of personnel changes in the band. Boot Hill was our original keyboard player but was replaced by Harry Phillips. Other changes were with guitar and bass, and the final recording ended up having two different groups of musicians from many different sessions. Barry talked Eddy Kramer, the engineer and co-producer for Jimi Hendrix, into coming to Detroit to listen to and mix some of the early tracks, but ultimately the production fell into the hands of Bob Ezrin. John Sauter and Ron Cooke appeared on bass, and Ray Goodman had been cut to make room for Mark Manko and Steve Hunter on guitar.

The photograph on the back of the

Detroit

album showed us, left to right: J.B. Fields, John Badanjek, Harry Phillips, Dirty Ed (Oklazaki), Steve Hunter, Ronnie Cooke, and me. One of our

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher