![Fatherland]()

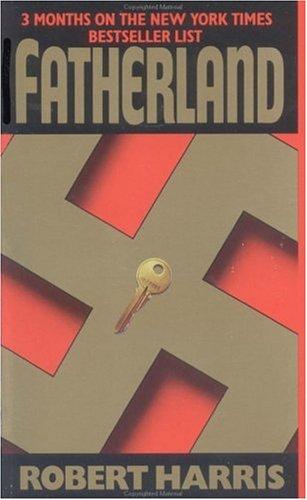

Fatherland

suits, reading pink financial newspapers. March had a seat next to the window. The place beside his was empty. He stowed his suitcase in a compartment above his head, settled back and closed his eyes. Inside the plane, a Bach cantata was playing. Outside, the engines started. They climbed the scale from hum to brittle whine, one coming in after another like a chorus. The aircraft jolted slightly and began to move.

For thirty-three hours out of the past thirty-six March had been awake. Now the music bathed him, the vibrations lulled him. He slept.

He missed the safety demonstration. The takeoff barely penetrated his dreams. Nor did he notice a person slip into the seat beside him.

Not until they were cruising at ten thousand meters and the pilot was informing them that they were passing over Leipzig did he open his eyes. The stewardess was leaning toward him, asking him if he wanted a drink. He started to say "a whisky" but was too distracted to finish his reply. Sitting next to him, pretending to read a magazine, was Charlotte Maguire.

The Rhine slid by beneath them, a wide curve of molten metal in the dying sun. March had never seen it from the air. "Dear Fatherland, no danger thine: / Firm stands thy watch along the Rhine." Lines from his childhood, hammered out on an untuned piano in a drafty gymnasium. Who had written them? He could not remember.

Crossing the river was a signal that they had passed out of the Reich and into Switzerland. In the distance: mountains, gray-blue and misty; below: neat rectangular fields and dark clumps of pine forests, steep red roofs and little white churches.

When he had awakened she had laughed at the surprise on his face. You may be used to dealing with hardened criminals, she had said, and with the Gestapo and the SS.

But you've never come up against the good old American press.

He had sworn, to which she had responded with a wide-eyed look, mock innocent, like one of Max Jaeger's daughters. An act, deliberately done badly, which made it naturally an even better act, turning his anger against him, making him part of the play.

She had then insisted on explaining everything, whether he wanted to listen or not, gesturing with a plastic tumbler of whisky. It had been easy, she said. He had told her he was flying to Zürich that night. There was only one flight. At the airport she had informed the Lufthansa desk that she was supposed to be with Sturmbannführer March. She was late: could she please have the seat next to him? When they agreed, she knew he must be on board.

"And there you were, asleep," she concluded. "Like a babe."

"And if they had said they had no passenger called March?"

"I would have come anyway." She was impatient with his anger. "Listen, I already have most of the story. An art fraud. Two senior officials dead. A third on the run. An attempted defection. A secret Swiss bank account. At worst, alone, I'd have picked up some extra color in Zürich. At best I might have charmed Herr Zaugg into giving me an interview."

"I don't doubt it."

"Don't look so worried, Sturmbannführer—I'll keep your name out of it."

Zürich is only twenty kilometers south of the Rhine. They were descending quickly. March finished his Scotch and set the empty container on the stewardess's outstretched tray.

Charlotte Maguire drained her own glass and placed it next to his. "We have whisky in common, Herr March, at least." She smiled.

He turned to the window. This was her skill, he thought: to make him look stupid, a Teutonic flatfoot.

First she had failed to tell him about Stuckart's telephone call. Then she had maneuvered him into letting her join in his search of Stuckart's apartment. This morning, instead of waiting for him to contact her, she had talked to the American diplomat, Nightingale, about Swiss banks. Now this. It was like having a child forever at your heels—a persistent, intelligent, embarrassing, deceitful, dangerous child. Surreptitiously he felt his pockets again, to check that he still had the letter and key. She was not beyond stealing them while he was asleep.

The Junkers was coming in to land. Like a film gradually speeding up, the Swiss countryside began rushing past: a tractor in a field, a road with a few headlights in the smoky dusk, and then—one bounce, two—they were touching down.

Zürich airport was not how he had imagined it. Beyond the aircraft and hangars were wooded hillsides, with no evidence of a city. For a moment, he wondered

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher