![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

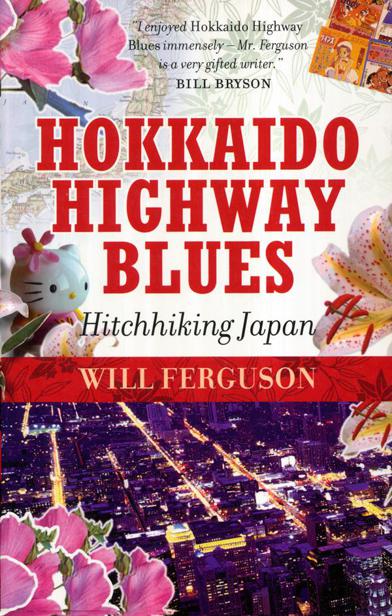

Hokkaido Highway Blues

could continue forever into Japan, turning corners, moving down alleyways, lost in the layers, captivated by vignettes.

Having abandoned my search for Mercy and the Mountain, I stumbled upon the way. It was like a Zen koan: when you pursue it eludes, when you stop, it seeks you out. Or maybe it was just dumb luck. Either way, I was happy. I had discovered a path that ran behind a temple and wound its way through a wooded park and a cemetery, and then finally to the Goddess Herself/Himself.

Kannon is sometimes male, sometimes female, but after the bombardment of the sex museum this gender-shifting ability didn’t seem that remarkable. The Uwajima Kannon is in the form of a woman. Chalk-white and marble-cool, she looks out with the deep serenity of Buddhist statuary, across a valley filled with city, to the castle, perched on a hill of its own. These two peaks are islands on an urban sea. The city flows below and around them: Kannon and Castle, looking at each other across a gulf, refugees separated by a flood of ferroconcrete.

5

THEY CALLED IT Sengoku-Jidai, the “Era of the Warring States.” It was a time of civil war, when the samurai clans of Japan fought for control over the Land of Wa. It began with the uprisings of 1467 and didn’t end until 1600, with the Battle of Sekigahara and the ascension of the first of the Tokugawa shōguns. With this, the longest, most successful totalitarian regime in human history began: two and a half centuries of isolation and central control. Japan was tossed from one extreme to the other, from anarchy to tyranny, and between the two you have four hundred years of human history.

The Sengoku Jidai, immortalized in saga and song, has inspired countless sword-and-samurai chanbara movies—so named because the hero’s theme music is inevitably “chan-chan-bara-bara-chan-bara-chan.” In the West, children play cowboys and Indians. In Japan they plan chanbara, chasing stray cats and younger siblings down alleyways while armed with only a pair of sticks, one long the other short, the sword and dagger of the samurai class.

Japan was once a chanbara country: a land of noble warriors, ninja assassins, feudal lords, beautiful courtesans, and lots of castles. Castles hidden in valleys, fortified on plains, buttressed behind walls, haughty atop mountain passes. Today, only a dozen are still standing. Many more have been rebuilt as tourist attractions, with varying degrees of accuracy, but it is the extant castles that are treasured the most.

A persistent myth holds that most were destroyed by the United States during the firebombing of Japanese cities. This is not entirely true. There were a few glaring examples: Nagoya Castle with its golden tiger-fish, and of course Hiroshima Castle. Both have since been rebuilt to original scale. (In Hiroshima City I once overheard a tourist ask his Japanese guide, “Hiroshima Castle, is that an original or a reconstruction?” I winced so hard I got a facial spasm.)

Most of Japan’s castles were destroyed long before World War Two, first during the feudal wars and then later during unification, when the Tokugawa shōguns systematically dismantled and destroyed hundreds of castles under an edict limiting each clan lord to a single fortress. (In typical bureaucratic fashion, lords without castles were required to build one.) The goal was to confine the clan lords and solidify Tokugawa rule. It worked, and two and a half centuries of relative stability followed—but at what a cost.

Only 183 castles survived the Tokugawa shoguns. Then came the modernizing forces of the Meiji reformers, and the real destruction began. Beginning in 1873, 144 castles across Japan were dismantled, sold, or razed as Japan sought to “Westernize” itself through a kind of cultural shock therapy, the effects of which are still being felt. By the end of the Meiji period only thirty-nine castles were left standing. The American bombers of World War Two destroyed two dozen more, and today only twelve are left.

Japanese castles are not the dread granite bastions one associates with Europe. Japanese castles are delicate in appearance, like decorative wedding cakes poised above the treetops. They look down upon the townspeople huddled below as a lord might look down upon a vassal. Indeed, to call them castles is a bit of a misnomer. They were manors as much as anything, and their design was based more on ostentation and pride than on tactics—or even common

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher