![Intensity]()

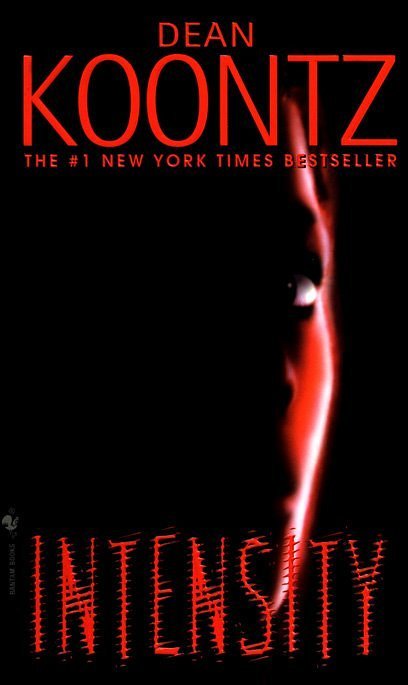

Intensity

wound. To accomplish this, she would have to sit, bend forward, and saw backward under the chair. Even if the upper chain had sufficient slack to allow her to reach down far enough for the task, which she doubted, she would only be able to scrape feebly at the wood. With luck, she'd whittle through the third stretcher sometime in the late spring. Then she would have to turn her attention to the five sturdy spindles in the back of the chair to free the upper chain, and not even a carnival contortionist born with rubber bones could get at them with a saw while pinioned as Chyna was.

Hacking through the steel chains was impossible. She would be able to get at them from an angle better than that from which she could approach the stretcher bars between the chair legs. But Vess wasn't likely to own saw blades that could carve through steel, and Chyna definitely didn't have the necessary strength.

She was resigned to more primitive measures than saws. And she was worried about the potential for injury and about how painful the process of liberation might be.

On the mantel, the bronze stags leaped perpetually, antlers to antlers, over the round white face of the clock.

Eight minutes past seven.

She had almost five hours until Vess returned.

Or maybe not.

He had said that he would be back as soon after midnight as possible, but Chyna had no reason to suppose that he'd been telling the truth. He might return at ten o'clock. Or eight o'clock. Or ten minutes from now.

She shuffled onto the floor-level flagstone hearth and then to the right, past the firebox and the brass andiron, past the deep mantel. The entire wall flanking the fireplace was smooth gray river rock-just the hard surface that she needed.

Chyna stood with her left side toward the rock, twisted her upper body to the left as far as possible without turning her feet, in the manner of an Olympic athlete preparing to toss a discus, and then swung sharply and forcefully to the right. This maneuver threw the chair-on her back-in the opposite direction from her body and slammed it into the wall. It clattered against the rock, rebounded with a ringing of chains, and thudded against her hard enough to hurt her shoulder, ribs, and hip. She tried the same trick again, putting even more energy into it, but after the second time, she was able to judge by the sound that she would, at best, scar the finish and chip a few slivers out of the pine. Hundreds of these lame blows might demolish the chair in time, turn it into kindling; but before she hammered it against the rock that often, suffering the recoil each time, she would be a bruised and bloodied mess, and her bones would splinter, and her joints would separate like the links in a pop-bead necklace.

By swinging the chair as though she were a dog wagging its tail, she couldn't get the requisite force behind it. She had been afraid of this. As far as she could determine, there was only one other approach that might work-but she didn't like it.

Chyna looked at the mantel clock. Only two minutes had passed since the last time she'd glanced at it.

Two minutes was nothing if she had until midnight, but it was a disastrous waste of time if Vess was on his way home right now. He might be turning off the public road, through the gate, into his long private driveway this very moment, the lying bastard, having set her up to believe that he would be gone until after midnight, then sneaking back early to-

She was baking a nourishing loaf of panic, plump and yeasty, and if she allowed herself to eat a single slice, then she'd gorge on it. This was an appetite she didn't dare indulge. Panic wasted time and energy.

She must remain calm.

To free herself from the chair, she needed to use her body as if it were a pneumatic ram, and she would have to endure serious pain. She was already in severe pain, but what was coming would be worse-devastating-and it scared her.

Surely there was another way.

She stood listening to her heart and to the hollow ticking of the mantel clock.

If she went upstairs first, maybe she would find a telephone and be able to call the police. They would know how to deal with the Dobermans. They would have the keys to get her out of the shackles and manacles. They would free Ariel too. With that one phone call, all burdens would be lifted from her.

But

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher