![Kushiel's Mercy]()

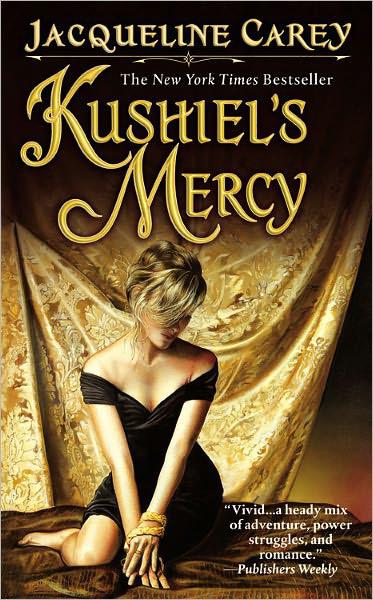

Kushiel's Mercy

with a dagger the day after I’d visited Valerian House for the first time. Phèdre adjusting the collar of my doublet on the day I’d wed Dorelei mab Breidaia.

That was the last memory.

As I lay sleepless, I thought about Dorelei and our unborn son. Their spirits slept now beneath a green mound in Clunderry, Berlik’s skull buried at their feet. I prayed for their forgiveness and understanding.

And I thought about Sidonie.

Ah, gods! Was simple happiness truly so much to ask? Was it ambitious to dream of a future in which we spent our lives together, taking pleasure in each other, in the bright mirror and the dark? In the heady abandon of love-play, in the homely comfort of watching our children dandled on the loving knees of their grandparents?

“Kushiel,” I whispered into the darkness. “I have spent my life trying to be good. I pray you hear your scion’s prayers. There is no one here in need of your harsh justice, only your mercy.”

There was no answer. Outside my narrow window, the moon inched closer to fullness in the night sky.

Some time after dawn, I arose hollow-eyed for lack of sleep and donned the clothing that the maidservant Clory had laid out for me. Black breeches and a black doublet. Mourning attire. It must have belonged to Joscelin.

It fit surprisingly well.

I descended the stairs to find the rest of the household likewise attired in mourning garb.

Joscelin eyed me critically. “You’re limping. I didn’t notice that yesterday.”

I opened my mouth to say that my healing wound stiffened when I slept, then caught myself. “I took a tumble on the ship in some rough waters and got a nasty bruise.”

Phèdre cocked her head at me. “Why didn’t Astegal’s ship continue up the Aviline? What made you decide to transfer to a barge?”

For the first time in my life, I had cause to curse her agile wits. “We thought it would be safer if no one knew Sidonie had returned,” I said. “We’d heard the rumors of impending war.”

She didn’t blink. “How did you know you could trust the barge-captain?”

“I don’t know.” I was too tired to invent a good lie. “Astegal had made plans for every contingency. You’d have to ask Kratos the details.”

It seemed to satisfy her, at least for the moment. I trusted Kratos would field the question with aplomb if Phèdre chose to pursue it. I hoped he’d slept better than I had.

Word came from the Palace before we’d finished breaking our fast; we were summoned to a funeral service in Astegal’s honor that afternoon. It would take place at the Temple of Elua, followed by a reception at the Palace. Ysandre and Drustan were moving swiftly; but then, there was precious little time to spare.

“I should attend as a member of House Courcel,” I said, rising from the table. “I’ll see you at the temple.”

Another glance exchanged.

“Imriel,” Phèdre said gently. “I think it’s best if you stay with us. I’m pleased that the physicians in Carthage were able to explain your situation in a way you could understand, but Sidonie’s in a great deal of pain right now. I fear worrying about your delusions is the last thing she needs.”

I gritted my teeth. “Actually, she said I was a solace. That it was a comfort to know that the last kinsman she expected had stayed loyal to the Crown.”

“I’m sure she did,” Phèdre said. “She’s always had a keen sense of propriety, even as a little girl. I never understood why you disliked her, any more than I can understand why your illness turned your feelings inside out.” She shook her head. “Nonetheless, give the poor child a moment’s peace.”

Joscelin’s hand closed on my shoulder. “Why don’t we spar? It will be like old times.”

I turned my head toward him. “Do you mean to keep me here forcibly?”

“Imri.” Joscelin’s grip tightened, then released. He caught my hand instead and raised it, baring my wrist to reveal the faint scars there. His eyes were grave. The vile threats I could never unsay, never forget I’d uttered, echoed in my memory. “We’re trying to help.”

I looked away. “I know. All right.”

I couldn’t begin to count the number of times I’d sparred with Joscelin: here in the inner courtyard of the townhouse, in the gardens of Montrève. The hilts of the wooden practice-swords we used were smooth and shiny with wear. He’d begun teaching me on the deck of a ship bound for Menekhet when I was ten years old. Betimes when I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher