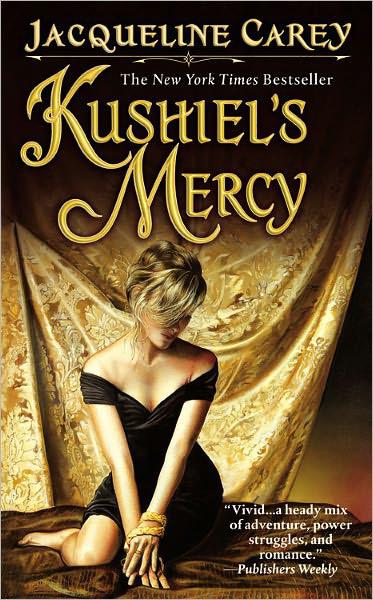

![Kushiel's Mercy]()

Kushiel's Mercy

tug, then smiled and touched my lips. “There will be other times. But as long as you’re on your knees, you may do penance. Lengthy, lengthy penance.”

That I did, freely and joyously. And she was right. I lost myself in her pleasure and hers alone, worshipping her with lips and tongue until she cried out, fingers clenched in my hair, and I had to grasp her hips to steady her.

And when it was done, when I couldn’t wring another spasm of pleasure from her, I felt calm and at peace. Mayhap we couldn’t set everything that was wrong in the world to right, but as long as all was well between us, it was enough.

Sidonie’s grip eased, and she gave a long, shuddering sigh. “Good boy.”

Still on my knees, I grinned at her. “You’re an easy mistress.”

It was the following day that everything began to converge. Drustan and his escort of Cruithne arrived at last. Phèdre and Joscelin returned from Montrève. The Queen and Cruarch spent a day closeted in consultation, while I did much the same with my foster-parents.

“I don’t like it.” Joscelin shook his head. “’Tis too easy.”

“I know,” I said. “But I can’t fathom where the risk lies.”

“Nor can I.” Phèdre rested her chin on her hand. “He asked naught but that Ysandre accept Carthage’s tribute? There was no implication that it implied a favor, a bribe?”

I showed her the letter and my transcription. “None.”

She studied it absently. “Well, mayhap Melisande’s made herself a thorn in Ephesium’s side somehow, and Agallon saw an opportunity to get rid of her and curry favor with Carthage at the same time.”

“Yes, but why does Carthage have a sudden burning desire to pay tribute to Terre d’Ange?” Joscelin asked. “If this General Astegal does mean to move against Aragonia, does he really think Ysandre can be bribed into looking the other way?”

“He might reckon it worth a try,” Phèdre said. “History is full of precedents.”

“Well, it’s a sizable tribute,” I said. “At least according to Quintilius Rousse.”

“What does Rousse say about the risk?” she asked.

I shrugged. “He’s not worried. There are only six ships, lightly armed. He’s got half the Royal Navy holding them at bay. He’s willing to follow them up the Aviline, and recommended Ysandre bring the bulk of the Royal Army inside the walls of the City.”

“I still don’t like it,” Joscelin said.

“Be as that may, my love,” Phèdre observed, “we’re not the ones to choose. We can advise Ysandre to be wary, but Parliament has the final say.”

It was true, but it was also true that no one with a seat in Parliament—with the exception of me and Sidonie, who had gained a vote upon reaching her majority—knew about the Unseen Guild. I didn’t know if that mattered, if it should play a role in my own decision, and if so, what?

Phèdre and Joscelin spoke to Drustan and Ysandre in a private audience. Sidonie and I discussed the matter endlessly. After hours of talking, none of us were any the wiser.

Ysandre convened Parliament.

There were seventy-two members all told: ten hereditary seats for each of the seven provinces of Terre d’Ange, the Queen, and her heir. When a sitting regent didn’t have an heir of age, they were allotted two votes. A simple majority of those present would constitute a binding vote. If there was a tie, the regent’s vote decided the matter.

It was rare to have the full complement of members present when Parliament was convened, and if the matter was a delicate one, many members chose to abstain; but for that session, we very nearly did. Those unable to attend sent a properly authorized delegate. Word had leaked out across the realm that the Carthaginian tribute was impressive, and curiosity and greed made for a powerful incentive.

It was an open session in the Hall of Audience, every seat along the long, curved tables filled, and a throng of avid onlookers pressed together in the back of the hall. The place was buzzing like a beehive, but it fell silent when Ysandre, seated at the center of the table, raised her hand.

“An offer lies before us,” she announced. “Lord Admiral, will you present it?”

The Palace Guard cleared a path for the Royal Admiral Quintilius Rousse. He strode into the hall with a rolling seafarer’s gait, bluff and hearty despite the grey salting his ruddy hair. There was a chalice tucked under one arm. He swept a deep bow, then placed it on the table

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher