![Love Songs from a Shallow Grave]()

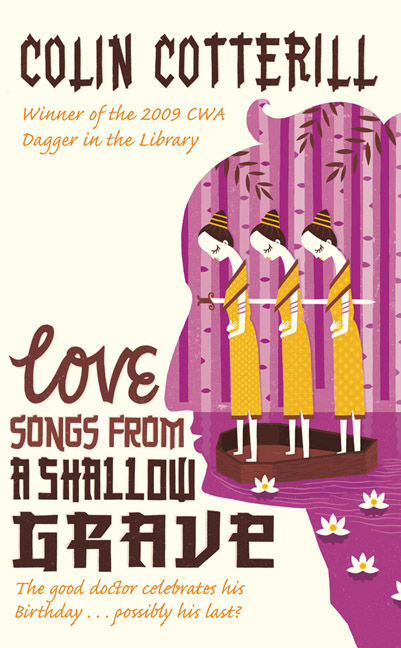

Love Songs from a Shallow Grave

she’d been forced to lock the front shutters and shout her conversations from the upstairs window. And then she stopped shouting and they stopped coming.

She walked along the upstairs landing and into the bedroom. She didn’t bother to turn on the light. She knew where the bed was. She’d lain awake in it for a month. The heroin she’d secreted in her altar to give her relief from rheumatism was currently dulling her grief. It stopped the tears and fuzzed reality, but it robbed her of sleep. She went to the window. The rains had moved south, flooding all their silly collective paddies and creating brand-new disasters for her country. And there was more to come. Monsoons were lashing China to the north and filling her darling Mekhong. Only June and all the sandbanks had sunk and logs sped past her shop with a menace that suggested her river was in a foul mood.

“Don’t even think about swimming to freedom,” it snarled.

Crazy Rajid was back. She could see him in the shadows. He sat on his Crazy Rajid stool under his Crazy Rajid umbrella. She wondered if he was the only sensible one of the lot of them. He hadn’t found anyone. And what you don’t find you don’t lose. He’d slept behind his father’s house when the rains were at their worst but, as far as she knew, he still hadn’t spoken to Bhiku. And she understood. She knew exactly why he held his tongue. Rajid had loved his mother and his siblings and they’d drowned. In his head it was quite obvious that his love had killed them. So how could he continue to love his father? Hadn’t he killed enough people? He had to hate his father because he loved him so much. Just as Daeng hated Siri.

She waved but wasn’t surprised at all when he didn’t wave back.

“Good man,” she said. “Keep your distance. Love stinks.”

She walked to the bed and, fully dressed, curled herself onto the top cover.

∗

He sat on his stool and looked up at the window. His thoughts were slow and his memory affected but he couldn’t forget that sweet woman, Daeng, who was admiring her river. He could understand what she saw in it. It was different every day. The water that passed you this minute would never come back. One chance to see the fallen tree. One shot at the bloated buffalo carcass. Everything was new. It didn’t have or need a memory. He loved the river too but today it had almost taken his life. It wasn’t a valuable life but he’d decided it was worth hanging on to. He was wet through and exhausted. And he was crying. Not many people had seen him cry. Some thought he had no real emotions. Thought he was cold. But that wasn’t true. He was nothing but emotions. His body was just a skin to hold all the emotions in. That’s why he was such a weakling. Why he had to pretend to be what he wasn’t.

He stood, lowered the umbrella, tied the drawstring and walked towards the shop. He’d started to feel the cold and he knew the chill was coming from inside him. It wouldn’t be long before a fever took hold. He needed to eat. He needed dry clothes. But, most of all, he needed to be wanted. He stopped on the pavement beneath her window. A bin for rubbish – half an oil drum – stood there. In it were the broken remnants of a spirit house and an altar. Someone had tried to set light to them but nothing burned in this weather. He stepped up to the grey shutters and a massive sigh shuddered in his throat.

“What if she hates me? What will I do then?” But it was too late to consider the negatives. He raised his fist and banged on the metal. Not one or two polite knocks but thunder, banging so hard that if she didn’t come down he would pummel his fist-prints into the steel. He’d hammer a hole in the metal and step inside.

∗

Daeng might have found rest but she hadn’t expected to find sleep. And when the hammering began she gave up on both. Why didn’t they leave her alone? She put the pillow over her head. It was musty from the stains of tears. If she couldn’t hear the noise perhaps it would eventually stop. But it went on, gnawing through the kapok, ‘thump, thump’. And she might have let it continue but for the memory of Rajid on his stool. The possibility that he might be hungry, or ill.

She went to the window. He wasn’t there. She leaned over the sill.

“Rajid, is that you?”

The banging continued.

“Rajid?”

The sound stopped.

“Rajid! I’m up here.”

Because the view was blocked by the awning, a visitor had to step back

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher