![Midnight Honor]()

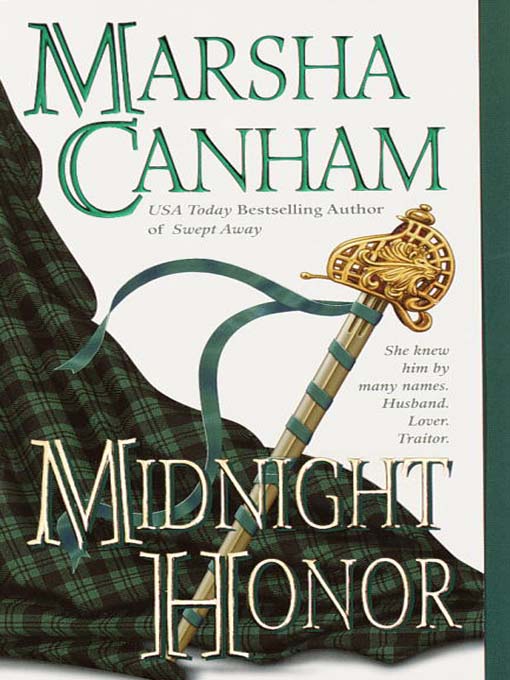

Midnight Honor

think about it? What then?”

“Then … I feel like the world's biggest coward, because I just want to run and hide somewhere and hope that no one will ever find me.”

“Bah!” He put a gentle hand on her shoulder and, although he had not intended them to do so, his fingers found their way beneath her hair to the nape of her neck. “We all feel that way sometimes. Ye think I've never lain awake at night wonderin' how it would feel to have the wrong end of an English bayonet in ma gut?”

“I don't believe that,” she said on a wistful sigh. “I do not believe you are afraid of anything, John MacGillivray.”

“Then ye'd be wrong,” he said after a long, quiet moment. “Because I'm dead afraid o' you, lass.”

Anne slowed further, then stopped altogether. She became acutely aware of his fingers caressing the back of her neck. She knew it had been meant as a friendly gesture, nothing more, and yet… when she looked at him, when she felt the sudden tension in his hand that had come with the hoarse admission, she knew it was not the caress of a man who wanted only to be a friend.

Perhaps it was the closeness of his body, or the lingering effects of too much ale. Perhaps it was because there were too many stars, or because the skirling of the pipes was throbbing in her blood. Or perhaps it was just because they were alone for one of the few times she'd permitted such a lapse in judgment, knowing all too well how the tongues were wagging about them already.

Perhaps it was for all those reasons and more besides that she reached up and took his hand in hers, holding it while she turned her head and pressed her lips into his callused palm.

“It's yer eyes, I think,” he said, attempting a magnificent nonchalance. “They suck a man in, they do, so deep he disna think he can ever find his way out again. An' it makes him wonder … about the rest. If it would feel the same.”

Anne felt the rush of heat clear down to the soles of her feet, and she bowed her head, still holding his hand cradled against her cheek. An image was in her head, so strong it sent shivers down her spine, of this hand and the other moving over her bare skin, sliding over skin slicked with oil and warmed by his body heat. Another heartbeat put her against that damned wall at the fairground again, and she knew what he had to offer, knew what he could offer her now if she but gave him a sign.

“It would be wrong,” she said softly.

“Aye. It would.”

“I love my husband,” she insisted, not knowing whether she was trying to convince him, or convince herself. “Despite everything that has happened, all the harsh words, the terrible disappointments … I do still love him.”

“Then ye've naught to worry about. Ye need only leave go of ma hand, walk straight the way into yer cottage, into yer own bed, an' we'll pretend this conversation never happened.”

“Can we do that?”

“We'll have no choice, will we?”

Was he asking her or telling her? She tilted her face up, meeting eyes that were black as the night, burning with an emotion she did not even want to acknowledge, for if she did, she would reach out to him with her body and her soul, and they would both lose the battles they were waging within themselves.

“It would be for the best,” she agreed.

“Aye. It would.”

She lowered her hand. He lowered his. And they each exhaled a steamy puff of breath.

Suddenly cold, Anne hugged her arms and drew her plaid tighter around her shoulders. They had stopped at the end of the neat little stone path that led to the front of the cottage; a lamp had been left in the window, the latter made of pressed sheets of horn so that the glow was diffused and did not reach past the overhanging thatch on the roof.

It was simple, one large room with a pallet in one corner, a table in the other. There might have been more furniture—a chair or a stool, and pots on the wall—but at the moment, Anne could only recall the bed.

“I'd best leave ye here, then,” John said, his voice tense with the conflict between loyalty and desire. “Ye'll be all right?”

“I'll be fine. John—!”

He had turned to leave, but at her call, he looked back—so quickly she almost took an instinctive step toward him.

And would that be so terrible? The English army was half a day's march away. MacGillivray would be leading the MacKintoshes into battle. He would be in the front line, the first to step onto the field, the first to break into

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher