![Pilgrim's Road]()

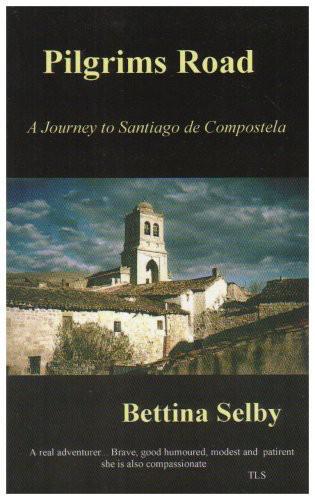

Pilgrim's Road

illusion is even stronger. The band of pilgrims on the door of the Hospital del Rey, with their staffs and broad-brimmed hats, their stout footwear, scrips and gourds would seem far less out of place on these ancient highways than would I on Roberts.

At Olmillos, where I parted from the N120, there was an arresting semi-ruined castle, possibly a Templar stronghold. I did not have the opportunity to study it in any detail because as soon as I stopped a rough-looking man, very much the worse for drink, came up and seized hold of Roberts’ handlebars. He was probably quite harmless and, as far as I could make out, he only wanted me to accompany him to the nearby bar, but he had so little control of his legs and was lurching about so much that he nearly had us all over in a heap on the road. Extricating myself and Roberts from his grasp was no easy matter and, having seized my moment, I slipped off down a narrow lane, leaving the castle and the interesting little village unexplored.

The broad plain was out of sight to the north, and my way now led across an open meseta, a bleak, parched land, where the thin fields showed the unremitting back-breaking toil of centuries. Mounds of stones picked from the earth were dotted about everywhere, but had never been used to build walls or windbreaks. A shepherd moved slowly across a wide sweep of the hillside, calling to his flock of earth-coloured sheep as he went, cajoling and scolding them continuously in a high-pitched voice. I could have imagined myself back in the vast spaces of Asia, for under the wide bright skies with the doleful clanking of the sheep bells the scene had an air of desolate grandeur.

Walkers frequently complained of this particular stretch being monotonous and interminable, but at the pace of the bicycle there was enough change and detail to hold the interest, and I found it one of the strangest and most satisfying sections of the journey. The ancient stone crosses that marked each small crossroads, a small valley where a life-giving spring had created a green oasis, the scattered ruins of lonely farms and an occasional village — a single street of squat top-heavy stone-built houses — all assumed a heightened importance in the wild barrenness of the landscape.

Nearer to Hontanas, where I was planning to spend the night, the land grew a touch more gracious. Hontanas means fountains, and clearly water was the key to settlements in this dry land. The small fields and gardens around the village seemed almost lush in comparison with the open meseta. Hontanas itself was impressive and more like a real pilgrim village than anything I had yet seen. A church of enormous proportions dominated the twenty or thirty houses built of rough stone, wattle and daub which clustered around it. The narrow winding streets, havens against the biting winds of the meseta and the intense heat of summer, were warm now, yellow in the afternoon sun and redolent of byres and baking bread. The charm of the old dwellings was not seriously marred by the addition of the occasional modern aluminium window frame, but more than half the houses were empty and in varying stages of decay. There had been a serious leaching of the population to the city over the past few years, as has happened in rural areas all over Europe.

The refugio was at the top of the small newly restored town hall — OPERA VINCIT 1765. The room was low-ceilinged, with a shuttered window a foot square, set just beneath the beetling eaves. It contained six bunk beds cheek-by-jowl, with barely space enough to pass between them. A tiny room across the landing housed a lavatory and a wash basin with a single cold tap. I thought it would have proved a difficult place in which to practise true Christian charity had it been full, but once again I would be spending the night alone.

I had not had a proper wash in days and, unlike a medieval pilgrim, the need for cleanliness had been bred into me as an essential of decent living. Unless I removed the invisible layer of sweat which clogged my pores I not only felt uncomfortable, I also suffered the dismal guilt of having failed in my duty. Nevertheless, it took no small degree of will power to wash even essential parts in the ice-cold water of Hontanas. I tried to concentrate on thoughts of the Celtic monks of old, standing all night long up to their chests in the freezing seas off the coasts of Scotland and northern England, while they recited the Psalms. But even with

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher