![Pilgrim's Road]()

Pilgrim's Road

this encouraging example my efforts produced no elevation of the spirit to accompany the mortification of the flesh. I was just relieved to get it over.

Cold had been the worst single hardship I had endured on the journey so far. In spite of the bright skies, it had remained decidedly chilly, and in true Spanish style, it always seemed to be far colder indoors than out. Not expecting such low temperatures, I had brought inadequate clothing — no woollens or thermals. I was more or less all right cycling because the exercise kept me warm, except on long downhill stretches. My fingerless riding gloves, however, were totally inadequate, and my hands were usually frozen, as were my ears. I would have bought another pair of gloves and a woolly hat had I been able to find any suitable ones, but such things had proved impossible to come by so far, and I could only hope that I might be able to buy some in León before I reached the mountains. To protect my eyes and stop them streaming with water in the wind, I wore my peaked beret pulled well forward over my goggles. This made the beret look like a peaked cap, and in spite of the silver scallop shell badge on the front, some people mistook me for a man.

But the worst effect of the cold was felt in the evenings. After the demands made upon it by strenuous exercise, the body cools down rapidly, and washing in ice-cold water reduces its temperature still further. My solution was to pile on all the clothes I had and sit swathed in my sleeping bag while I wrote or read, blowing life back into my freezing fingertips from time to time. This was very much in keeping with the medieval period, when it had always been the custom in northern climes to don extra layers of clothing on entering the dank castles and draughty halls. Cold water didn’t make laundering easy either. The only items I bothered with usually were underwear; pinned to the panniers the next day these dried quickly in the wind. Once a week I made a real effort to wash shirts and socks.

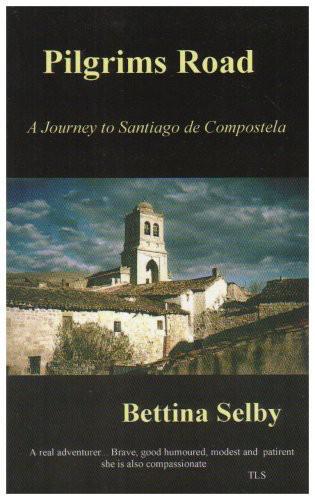

Temperature aside, Hontanas proved a happy choice of lodgings. Clean and sanctified I went out to take photographs of the village before the light went. One advantage of this cold weather was the marvellous light and cloud effects, and nowhere were these more magnificent than the evening I spent in this pilgrim village. The mackerel clouds had darkened a shade to absolute perfection, and the grey church and houses against the darkly luminous sky seemed tremendously beautiful and tragic at the same time, reflecting as they did what was temporal and passing against what was eternal. ‘The sad hour of Compline’ was the phrase that came to mind again as I composed my photographs, just as it had the evening at La Réole overlooking the river and watching the people taking their evening stroll. The feeling was more intense here, the effect no doubt of the ride through the harsh implacable landscape which made the human condition seem more fragile than ever.

Doña Anna, who kept the key of the refugio and lived a few doors away from it, had agreed to cook my supper that evening. She knew a little French, having learnt it with great difficulty, she said, while working in a clinic in France before her marriage. The suburban interior of her house was a strange contrast to the ancient structure, but it was warm and cheerful which was far more important. Anna made me a tortilla — very solid and satisfying — and with some locally produced sweet red wine to go with it, and basking in the warmth of the fire, the last threads of melancholy disappeared. Her thirteen-year-old daughter, Consuela, kept me company while I ate, trying out the flat English phrases she was currently learning at school in Burgos. Anna was very proud of the child and eager to hear her skills praised. She considered education was very important, for there was no future for children in the village. Most of them had to make their living away from home. If Consuela did well, she could maybe find work in Burgos and travel in every day like her father who was a mechanic. Her chubby son, a few years younger than Consuela, poked his head around the door at that point and made a remark to which his mother responded by pretending to box his ears. For this one, she said, she had no hopes at all, her fond looks belying the words. He was idle, good for nothing and cheeky, and again she pretended to cuff his ears while he barely ducked, smiling broadly, secure in her affection

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher