![Pnin]()

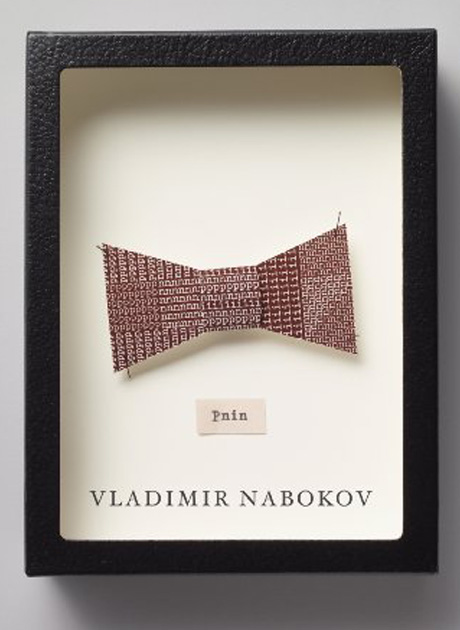

Pnin

my butterfly. A fortnight later I was somehow or other compelled to attend the performance. The barn was full of dachniki (vacationists) and disabled soldiers from a nearby hospital. I came with my brother, and next to me sat the steward of my aunt's estate, Robert Karlovich Horn, a cheerful plump person from Riga with bloodshot, porcelain-blue eyes, who kept applauding heartily at the wrong moments. I remember the odour of decorative fir branches, and the eyes of peasant children glistening through the chinks in the walls. The front seats were so close to the stage that when the betrayed husband produced a packet of love-letters written to his wife by Fritz Lobheimer, dragoon and college student, and flung them into Fritz's face, you could see perfectly well that they were old postcards with the stamp corners cut off. I am perfectly sure that the small role of this irate Gentleman was taken by Timofey Pnin (though, of course, he might also have appeared as somebody else in the following acts); but a buff overcoat, bushy mustachios, and a dark wig with a median parting disguised him so thoroughly that the minuscule interest I took in his existence might not have warranted any conscious assurance on my part. Fritz, the young lover doomed to die in a duel, not only has that mysterious affair backstage with the Lady in Black Velvet, the Gentleman's wife, but toys with the heart of Christine, a naïve Viennese maiden. Fritz was played by stocky, forty-year-old Ancharov, who wore a warm-taupe make-up, thumped his chest with the sound of rug beating, and by his impromptu contributions to the role he had not deigned to learn almost paralysed Fritz's pal, Theodor Kaiser (Grigoriy Belochkin). A moneyed old maid in real life, whom Ancharov humoured, was miscast as Christine Weiring, the violinist's daughter. The role of the little milliner, Theodor's amoretta, Mizi Schlager, was charmingly acted by a pretty, slender-necked, velvet-eyed girl, Belochkin's sister, who got the greatest ovation of the night.

3

It is improbable that during the years of Revolution and Civil War which followed I had occasion to recall Dr Pnin and his son. If I have reconstructed in some detail the precedent impressions, it is merely to fix what flashed through my mind when, on an April night in the early twenties, at a Paris café, I found myself shaking hands with auburn-bearded, infantine-eyed Timofey Pnin, erudite young author of several admirable papers on Russian culture. It was the custom among émigré writers and artists to gather at the Three Fountains after the recitals or lectures that were so popular among Russian expatriates; and it was on such an occasion that, still hoarse from my reading, I tried not only to remind Pnin of former meetings, but also to amuse him and other people around us with the unusual lucidity and strength of my memory. However, he denied everything. He said he vaguely recalled my grand-aunt but had never met me. He said that his marks in algebra had always been poor and that, anyway, his father never displayed him to patients; he said that in Zabava (Liebelei) he had only acted the part of Christine's father. He repeated that we had never seen each other before. Our little discussion was nothing more than good-natured banter, and everybody laughed; and noticing how reluctant he was to recognize his own past, I switched to another, less personal, topic.

Presently I grew aware that a striking-looking young girl in a black silk sweater, with a golden band around her brown hair, had become my chief listener. She stood before me, right elbow resting on left palm, right hand holding cigarette between finger and thumb as a gipsy would, cigarette sending up its smoke; bright blue eyes half closed because of the smoke. She was Liza Bogolepov, a medical student who also wrote poetry. She asked me if she could send me for appraisal a batch of her poems. A little later at the same party, I noticed her sitting next to a repulsively hairy young composer, Ivan Nagoy; they were drinking auf Bruderschaft, which is performed by intertwining arms with one's co-drinker, and some chairs away Dr Barakan, a talented neurologist and Liza's latest lover, was watching her with quiet despair in his dark almond-shaped eyes.

A few days later she sent me those poems; a fair sample of her production is the kind of stuff that émigré rhymsterettes wrote after Akhmatova: lackadaisical little lyrics that tiptoed in more or less anapaestic

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher