![Pnin]()

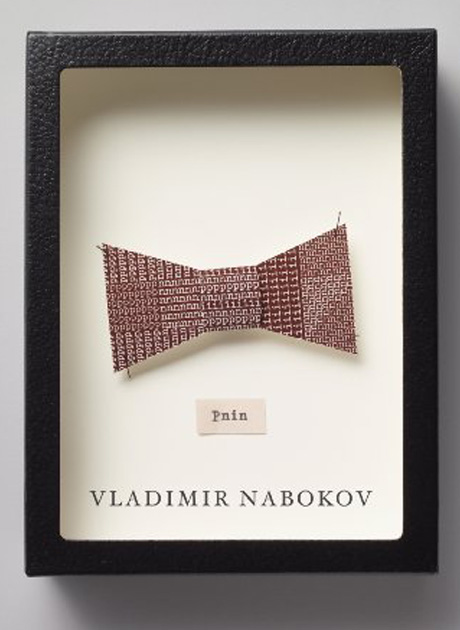

Pnin

flies kept describing slow quadrangles around the lifeless chandelier. A lady, wearing a plumed hat, and her dark-spectacled husband were sitting in connubial silence on the davenport; then a cavalry officer entered and sat near the window reading a newspaper; then the husband repaired to Dr Pnin's study; and then I noticed an odd expression on my tutor's face.

With my good eye I followed his stare. The officer was leaning toward the lady. In rapid French he berated her for something she had done or not done the day before. She gave him her gloved hand to kiss. He glued himself to its eyelet - and forthwith left, cured of whatever had ailed him.

In softness of features, body bulk, leanness of leg, apish shape of ear and upper lip, Dr Pavel Pnin looked very like Timofey, as the latter was to look three or four decades later. In the father, however, a fringe of straw-coloured hair relieved a waxlike calvity; he wore a black-rimmed pince-nez on a black ribbon like the late Dr Chekhov; he spoke in a gentle stutter, very unlike his son's later voice. And what a divine relief it was when, with a tiny instrument resembling an elf's drumstick, the tender doctor removed from my eyeball the offending black atom! I wonder where that speck is now? The dull, mad fact is that it does exist somewhere.

Perhaps because on my visits to schoolmates I had seen other middle-class apartments, I unconsciously retained a picture of the Pnin flat that probably corresponds to reality. I can report therefore that as likely as not it consisted of two rows of rooms divided by a long corridor; on one side was the waiting-room, the doctor's office, presumably a dining-room and a drawing-room farther on; and on the other side were two or three bedrooms, a schoolroom, a bathroom, a maid's room, and a kitchen. I was about to leave with a phial of eye lotion, and my tutor was taking the opportunity to ask Dr Pnin if eyestrain might cause gastric trouble, when the front door opened and shut. Dr Pnin nimbly walked into the passage, voiced a query, received a quiet answer, and returned with his son Timofey, a thirteen-year-old gimnazist (classical school pupil) in his gimnazicheskiy uniform - black blouse, black pants, shiny black belt (I attended a more liberal school where we wore what we liked).

Do I really remember his crew cut, his puffy pale face, his red ears? Yes, distinctly. I even remember the way he imperceptibly removed his shoulder from under the proud paternal hand, while the proud paternal voice was saying: 'This boy has just got a Five Plus (A +) in the Algebra examination.' From the end of the corridor there came a steady smell of hashed-cabbage pie, and through the open door of the schoolroom I could see a map of Russia on the wall, books on a shelf, a stuffed squirrel, and a toy monoplane with linen wings and a rubber motor. I had a similar one but twice bigger, bought in Biarritz. After one had wound up the propeller for some time, the rubber would change its manner of twist and develop fascinating thick whorls which predicted the end of its tether.

2

Five years later, after spending the beginning of the summer on our estate near St Petersburg, my mother, my young brother, and I happened to visit a dreary old aunt at her curiously desolate country seat not far from a famous resort on the Baltic coast. One afternoon, as in concentrated ecstasy I was spreading, underside up, an exceptionally rare aberration of the Paphia Fritillary, in which the silver stripes ornamenting the lower surface of its hindwings had fused into an even expanse of metallic gloss, a footman came up with the information that the old lady requested my presence. In the reception hall I found her talking to two self-conscious youths in university student uniforms. One, with the blond fuzz, was Timofey Pnin, the other with the russet down, was Grigoriy Belochkin. They had come to ask my grand-aunt the permission to use an empty barn on the confines of her property for the staging of a play. This was a Russian translation of Arthur Schnitzler's three-act Liebelei. Ancharov, a provincial semi-professional actor, with a reputation consisting mainly of faded newspaper clippings, was helping to rig up the thing. Would I participate? But at sixteen I was as arrogant as I was shy, and declined to play the anonymous gentleman in Act One. The interview ended in mutual embarrassment, not alleviated by Pnin or Belochkin overturning a glass of pear kvas, and I went back to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher