![Pow!]()

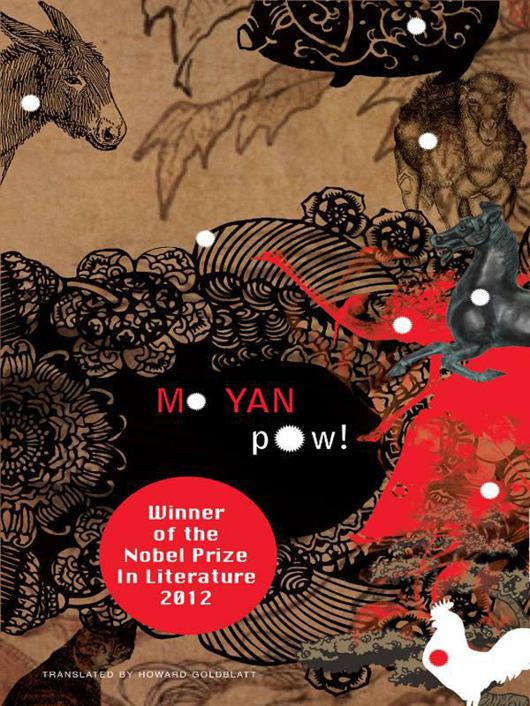

Pow!

his wounds, still shouting: ‘Kill me—kill me—’

We slammed the door shut; shouting, he attacked it with his substantial buttocks. His voice, which cut like a knife, sounded like it could slice through glass. We covered our ears with our hands but to no avail. The door was starting to give way, the hinges pulling free. A moment later it fell apart with a crash and the splintering of glass. Wan burst into the room: ‘Kill me—kill me—’

Jiaojiao and I slipped under his armpits and ran as fast as we could. But when we reached the street the motorcycle was following us, as were Wan Xiaojiang's shouts.

We ran out of the village and into the overgrown fields, but the rider—the man must have been a motorcross racer—rode straight into the waist-high grass and across the water-filled ditches, startling clusters of strange-looking hybrid animals out of their dens. As for Wan Xiaojiang, his unnerving shouts never stopped swirling round us.

That's what did it, Wise Monk. We left home and began living a rootless life, all to get away from that rotten Wan Xiaojiang. Three months later, we returned, and the minute we walked in the door of our home we discovered that we'd been cleaned out by thieves. No TV, no VCR, the cabinets thrown open, the drawers pulled out, even the pot was gone. All that was left were two stovetop frames, like a pair of ugly, toothless, gaping mouths. Fortunately, my mortar still rested in a side room under its dusty cover.

We sat in the doorway and watched the people on the street, both of us sobbing, high one moment, low the next. The neighbours brought jars, baskets, even plastic bags, all filled with meat, fragrant, lovely meat, and laid them at our feet. No one said a word. They just watched us, and we knew they wanted us to eat the meat they'd brought. All right, kind people, we'll eat it, we will.

We ate it.

Ate it.

Ate.

We ate so much we couldn't stand; we looked down at our bulging bellies and then crawled inside on our hands and knees. Jiaojiao said she was thirsty. So was I. But there was no water in the house. We looked round till we found a bucket under the eaves, half filled with foul water, perhaps rainwater from that autumn. Dead insects floated on the surface but we drank it anyway.

Yes, that's how it was, Wise Monk.

When the sun came up, my sister was dead.

At first I didn't realize it. I heard the meat screaming in her stomach and saw that her face had turned blue. Then I saw the lice crawling out of her hair and I knew she was dead. ‘Baby sister,’ I cried out, but I'd barely got the words out when chunks of undigested meat spilt from my mouth.

I vomited, my stomach feeling like a filthy toilet and the putrid smell of rotting food filling in my mouth. It was the meat, hurling filthy curses at me. Chunks of meat thrown up from my stomach began to crawl like toads…I was disgusted and filled with loathing. At that moment, Wise Monk, I vowed to never eat meat. I'd rather eat dirt from the road than a single bite of meat, I'd rather eat horse manure in a stable than a single bit of meat, I'd rather starve to death than a single bite of meat…

It took me several days to clear my stomach of meat. I crawled down to the river and drank mouthfuls of clean water with bits of ice in it; I ate a sweet potato someone had thrown onto the riverbank. Slowly my strength returned.

One day child came running up to me. ‘Luo Xiaotong. You're Luo Xiaotong, aren't you?’

‘Yes, but how did you know?’

‘I just know,’ he said. ‘Come with me. Someone is looking for you.’

I followed him into a two-room hut in a peach grove, where I saw the old couple who had sold us the beat-up mortar years earlier. The mule, now aged a great deal, was there too, standing alone beneath a peach tree eating dry leaves.

‘Grandpa, Grandma…’ I threw myself into the old woman's arms as if she really were my grandmother and wet her clothes with my tears. ‘I've lost everything,’ I sobbed. ‘I've got nothing. Mother's dead, Father's arrested, my sister's dead and I can't bear to eat meat any more…’

The old man pulled me out of her arms and smiled. ‘Look over there, son.’

There in the corner of the hut stood seven wooden cases. On them were printed words that were as unfamiliar to me as I was to them.

The old man opened one of the cases with a crowbar and peeled back a sheet of oiled paper to reveal six long, tenpin-shaped objects with wing-like

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher